Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, The Ordinary Magic of Storytelling, presented by Stephanie Goloway, EdD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify at least four ways that oral storytelling supports the development of young children.

- Describe the process of selecting, learning and telling stories to young children.

- Analyze ways that storytelling can be integrated into current early childhood curricula and daily routines.

What is Storytelling?

Today we're going to be talking about my very favorite topic in the world, The Ordinary Magic of Storytelling. To start out with, what is storytelling? Usually, when I tell people that we're going to do storytelling, they think about story reading, which is taking a picture book and sharing it with young children. Storytelling is not that. Storytelling is telling a story without the book. It's being able to share it orally with children or with other adults. We've been doing storytelling as a species since we became human.

You may have seen things on TV about cavemen etching out pictures on the walls of their caves of the hunt that they just completed or things like that. While we tend to look at those as art, anthropologists tell us that actually those are indications that they were telling stories and using those pictures to illustrate. Storytelling has been around forever. Before we had the printing press, storytelling was the only way that most people got both information and entertainment. Since the printing press came about, we have not ever dropped the use of storytelling as our way of communicating what's happened in our lives or our hopes and our dreams to the people around us. What we have done is shifted a lot of the sharing of the made-up stories to TV and to other media. We are going to talk about how that can support children's development in some ways, but in other ways, getting back to the basics of telling a story one to one or one to a group is really a powerful thing for child development.

I titled this course The Ordinary Magic of Storytelling for a couple of reasons. First, it's a nod to Dr. Ann Masten who did a lot of work that I think is important for us as early childhood educators to talk about resilience and how that develops. She called it "Ordinary Magic." We'll be talking a little bit more about that later. The other reason is that storytelling is ordinary. We do it all the time. It takes no resources or fancy equipment. It's just what comes out of us naturally. The effects of that, especially on young children, is truly magical. I hope that you'll join me and start to discover how magical it can be in your classroom as well.

Why Tell Stories?

We ALL tell stories…

- Science

- Literacy

- Relationships

- Culture

- Resilience

Why do we tell stories? We all tell stories and we do it all the time, but there are some significant reasons that telling stories in an early childhood classroom is really important. We are going to learn a little bit about what the neuroscientists tell us about why we should tell stories. We're going to learn about how storytelling supports emergent and early literacy and how storytelling can nurture relationships and social and emotional intelligence. We are so concerned about children's social and emotional intelligence and we want to make sure that our kids leave us with this. It also makes our days go a lot more smoothly. We're going to just touch on how storytelling is truly the way that all of our cultural backgrounds can merge together and we can more deeply understand each other.

Science

- Humans have always told stories

- Communication

- Learning

- Culture

- Mirror neurons

- Empathy

- “Doubleness”

- Risk and problem-solving

Let's start with science. Why do the neuroscientists tell us that storytelling is important? Humans have always told stories. We just talked about that. They have told stories for communication and they have told stories as a way of learning and sharing what they know and of sharing and perpetuating culture from generation to generation. All of that has affected the way that our brains have evolved and developed. As human beings, we're wired to be able to learn best when we are told things in story form. We remember stories better. We are engaged with stories more naturally. We have continued to learn more about why stories and storytelling have this impact on our brain.

We've learned more and more about neuroscience and are able to more carefully figure out what's going on inside the brain as well as what's going on outside of children. There is a concept called mirror neurons. The key idea is that in our brains we have neurons that are bubbling around that pick up on certain situations of what's going on outside of us and get activated in the same sort of way. Neuroscientists have discovered that when we hear stories our mirror neurons get stimulated. For example, if we hear the story of Jack and the Beanstalk and Jack is climbing up and up and up that beanstalk and all of a sudden he hears the shaking and the rumbling in the Giant's castle, our mirror neurons are stimulated in a way that Jack's would be. If we think that Jack is anticipating the giant, our mirror neurons that have to do with a little bit of fear and anticipation start to be activated. That's why we can empathize with the characters in the stories that we hear.

For young children, this is so critical because we want them to be able to develop empathy. For example, when they knock over Jimmy's block building and Jimmy is mad, we want them to know that and be able to care about it and feel it so that they won't do it again. Storytelling, as it turns out, is a wonderful way that we can help children develop empathy for a variety of different characters' emotions because of the way mirror neurons are activated.

There's also a concept called doubleness, which is a way that we can feel two emotions at the same time. Storytelling and stories like fairytales are especially adept at being able to help kids with this doubleness. How does that work? Let's say you are telling a story to a group of children and you are telling them about Jack. Jack suddenly gets to the top of the beanstalk, goes into the house, and hears the giant saying, "Fee-fi-fo-fum." The giant's wife says, "Quick, quick hide." As children are hearing this, they are feeling two things simultaneously. One is a delight in being able to be part of this storytelling with their friends and their teacher and feeling comfortable and happy because that's the mode that storytelling puts us in. At the same time, they are also having that little tinge of fear, anticipation, excitement, and whatever Jack is feeling. In order to continue to listen to a story, they have to regulate both of those different emotions at the same time.

When we talk about self-regulation, this is a wonderful way for children to start to develop the ability to regulate those emotions. They are not really scared, but they could be scared and they are able to balance that out through storytelling. They begin to explore what it feels like if things happen and you are at risk. Because they know that it is not real and that it is a story, they are also able to activate their problem solving and their objective thinking about a situation. This doubleness is very, very powerful when we think about how we are trying to help kids understand their own emotions as well as the emotions of others. It also helps them come to grips with the idea that they will encounter things that they do not know yet and that they are going to be okay.

Literacy

- Oral language development

- Fast-mapping

- Paralinguistics

- Understanding of story structure

- Mental imagery and reading

- Pretend play

- Emergent writing

Stories equal literacy. Most early and emergent literacy programs focus on stories and there are very good reasons for that. Storytelling, as well as reading, is really important to oral language development. When children hear vocabulary words that they are not familiar with, they learn more words and understand how language and sentences work. In order to be able to eventually read and write, they have to understand how oral language works and how to understand oral language when people are talking. Storytelling is really effective for this because of a couple of things that are not unique to storytelling, but that storytelling captures really well.

Fast Mapping

One of those is the idea of fast mapping. Fast mapping is the process of rapidly learning a new word by contrasting it with a familiar word. Young children develop oral language so rapidly, even hundreds of words a day. Think about adults trying to learn a foreign language and how slowly we add vocabulary then contrast that to a typical two-year-old and how quickly they learn a language. Fast mapping has a lot to do with it. The brain is uniquely geared during this early childhood period to take words that are heard and to fast map them or record them in the brain in the context of whatever meaning is surrounding them.

Think about a child who hears about Jack. Jack has climbed up and up and up the Beanstalk and goes into the giant's house. Mrs, Giant says, "Mercy, mercy, child, you must quickly, quickly hide because the ferocious giant, my husband, is about to come." What does ferocious mean? When we are telling kids stories, our facial expressions, hand expressions, and the context of what's going on in the story quickly give children an idea that ferocious, especially when rah, rah, rah, the giant comes in, means something kind of scary. Even if they have never heard the word ferocious before, they fast map that and that word ferocious becomes part of their working vocabulary so that when they encounter it later when they're reading it or when they're using it in oral language, it's theirs.

Paralinguistics

Storytelling can help with fast mapping and also what we call paralinguistics. Children learn to read gestures, facial expressions, and tones of voice. Those things all have to be learned. We know that they have to be learned because culturally, they're very different. If they were just embedded into us, all cultures would respond to body language in the same way. We don't. With storytelling, because you're focusing on a range of emotions and different actions, children can attach meaning to whatever it is that you are doing or saying in your paralinguistics. It's not just the words that they are hearing, but they are hearing your tone of voice and seeing your facial expressions and gestures. All of that gives them a vocabulary in paralinguistics as well, which helps them understand their friends and their families and what is going on in the world.

Understanding of Story Structure

Storytelling gives kids an understanding of story structure and how stories work, including the idea of every story having a beginning, a middle, and an end. They have characters, plots, and problems. When we tell children stories, especially folk and fairy tales, they have a very clear and consistent story structure. As children build up their vocabulary of how stories work, then when it comes time for them to do more formal reading activities, they go into reading with an expectation of understanding what's supposed to come next. They look for the beginning, middle, and end. They look for the characters, the plot structure with the problems, and it supports their early reading development as well as their future reading development as they get older.

Mental Imagery and Reading

Storytelling is also important for developing mental imagery, which is being able to see pictures in your head. If you like to read, when you read a book as an adult, you probably see pictures in your head. As you're reading a story, you are the person that you're reading about and you see the landscape. You understand what that house is going to be like. You put yourself in that story through your mental imagery. Like all of these other aspects of language development and representational thinking, imagery has to be developed. It is constructed by children. From the time they're born, they begin to slowly develop the capacity to construct pictures in their heads of things that are not physically present. This is developmental. Part of it is just a function of age, but a lot of it is also a function of experience.

In today's world, children are bombarded with outside images. If they sit in front of a TV to hear their stories, then SpongeBob looks one way. He doesn't look any other way. They don't have to imagine what Elsa looks like and whether she has pink skin or blue skin or brown skin. They know exactly what Elsa looks like. When we tell kids stories rather than even showing them pictures in books, they have to construct a picture in their minds of what the characters look like and what the environment looks like. Thinking about all of those kinds of things gives them a lot of practice for developing the ability to be able to see those pictures in their heads. That has a huge impact on their later reading as well as other aspects of language development and problem-solving.

Why don't we hear about mental imagery when we're hearing about how we teach kids how to read? We don't have a way of measuring what pictures people see in their heads. When researchers are looking for aspects of what makes a child a good reader and what kind of supports they need to be able to be an effective decoder and understander of texts that they read, they can't study mental imagery very well because it's inside our heads. At some point in time, maybe we'll have the technology through neuroscience to be able to plug little electrodes onto our heads and study how images are constructed. But for now, we don't have that empirical basis for that information.

We do know it works and we know it is important. I've talked to many people and asked them, "Do you see pictures in your head when you're reading for fun?" The people who say no are those who don't like to read. Storytelling is a way of developing both this foundational skill and becoming a better reader. The more fun you have reading because you see wonderful pictures in your head, the more you're going to want to read and the better reader you're going to become just because of practice.

Pretend Play

Storytelling also supports pretend play. Children play out the stories that they know in the classroom, whether they have heard them in the classroom or seen them on TV. We know that from just watching them do their pretend play. There is a lot of empirical research that supports the idea that the more rich and detailed children's pretend play is, the better a chance they have at a lot of different skills, including those foundational skills for early literacy. Stories feed into their pretend play which feeds into their ability to construct and take control of these mental images that they're creating.

Emergent Writing

All of this means that children are much better prepared for that process that we're all committed to, which is becoming good readers and writers once they hit a formal education. When kids make up their own stories, they are writing. They are storytellers and storytellers are the same thing as writing, and it all supports that rich background that we want them to have.

Relationships

- Need for connection

- Intimacy

- Building community through shared experiences

Why else tell stories? They help build relationships. Everything we know about early childhood is that we are a relationship-based field and that young children need healthy, supportive relationships in order to have productive lives, to be good, and to feel safe and secure. We need connections. As early childhood educators, we are that connection for many children during a big part of their day. When we tell stories, it allows us to create a sense of intimacy, even more so than with a book. I read books to children all the time. I'm not saying don't read books, but there's something very different between reading a book to a child and telling a child a story. They believe that the connection between you and them is stronger. They feel it emotionally. It is more like you're sitting on the carpet with them and having a conversation. When you're telling a story, even though you're telling to a group of 20 kids, there's an intimacy in storytelling that helps them to understand how all these relationships are supposed to work with people that care about them.

It also builds community in your classroom. There's the intimacy between the teacher and the child and that relationship, but also the relationship with their friends. When children are in the bubble of a told story together, they start to connect on that level of the story. Those characters will then go with them outside of circle time or outside of the storytime into their play, whether it's onto the playground or into the block area. They begin to connect with each other on this plane of not just being in the same classroom together, but being in the same story together. Stories have an effect that even children who are a little bit outside of the typical classroom routines know that they are part of the story too and they are included.

Culture

This brings us to culture. What I just described was that we have a culture in every classroom. You have a culture at your center or your school and your classroom has a culture. Each child has their own home cultures that they all bring into this shared culture of our classroom. Storytelling just by its nature helps us to understand these various cultural elements and to bring us together.

We talk a lot about equity and diversity and inclusion in early childhood, and these are just a part of storytelling. Every child has a story to tell. Every child is part of a shared story and that includes equity and inclusion. We have kids who come into our classrooms who are from very different cultures and might not even speak English as their first language. Their culture may have a completely different way of eating, addressing adults, or playing. Through stories, we can help all of those kids come together and see the value in each of these variations.

I personally love to share folk and fairy tales from all different cultures around the world. Cinderella, told by Disney, is one Cinderella story that most children are fairly familiar with. What about the Cinderella story from Iraq, Egypt, or Afghanistan? If you have a child in your classroom who comes from one of those cultures, sharing a story that is similar to, but not quite like ones the children already know is a wonderful way of helping kids to understand that even though there are all these cultural variations, we all understand the same stories and we all are part of the same human condition that stories help us to understand better.

Resilience

- Resilience: the ability to bounce back from adversity

- Protective factors for resilience:

- Attachment/Relationships

- Initiative

- Self-Regulation and Executive Functions

- Cultural Affirmation

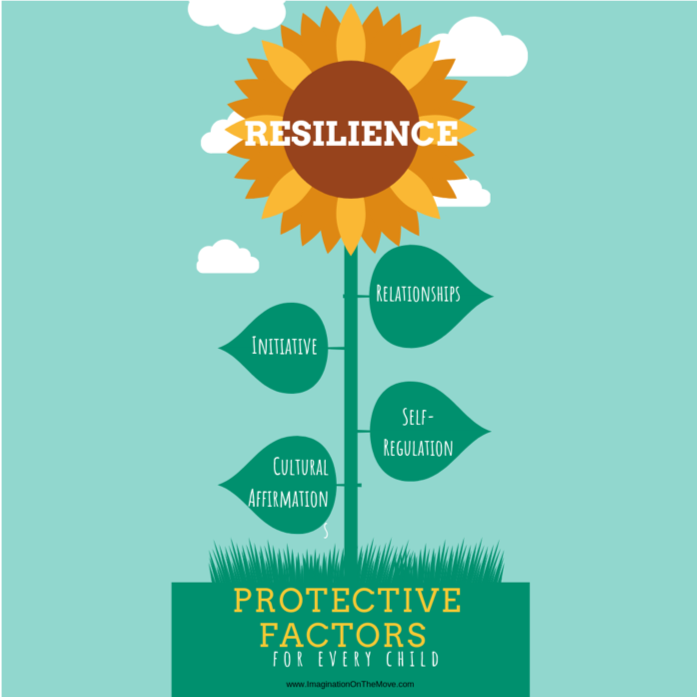

Figure 1. Resilience and protective factors.

Another reason to tell stories is resilience. Resilience is the ability to bounce back from adversity. A lot of my research focused on big trauma and diversity, living with substance use disorder, child abuse, family violence, and community violence. All of those things are something that many children live with. This also includes natural disasters and things that are going on in the news that they don't understand and that they feel scared of. All of those kinds of experiences can be traumatic. Those are all adversity. Adversity can also be not getting the color Popsicle that you really, really want at snack time. All of us face adversity at one time or another.

All of us need to develop what people have called resilience, which is the ability to bounce back from it. If you don't get the Popsicle, move on. Maybe you can have the red one tomorrow. For now, we still have lots of opportunities to play and have fun. If something really bad happens, you know what? You've got friends, you've got teachers, and you've got people who care about you. We're going to get you through this. Whether the adversities are tiny or huge, resilience is what psychologists and neuroscientists have told us is our brain's ability to be able to overcome the adversities and move forward as is necessary for a healthy and productive life.

Protective Factors for Resilience

We know a lot about resilience. I'm just going to give you a snippet of it. Figure 1 shows protective factors. This includes things that happen in a child's experiences, or that ordinary magic, that will allow them to develop the brain's capacity for resilience.

The first one is attachment and relationships. We've been talking all about that idea of how important relationships are and how storytelling actually helps to nurture them, especially the one-on-one intimacy with the story between the storyteller and the child or the group of children all sharing in the same story. These are ways that help to support this protective factor of attachment relationships for resilience.

Initiative is another factor that's been identified by people as part of resilience. If you feel like you have personal power or self-efficacy and you can feel comfortable acting on your own ideas, that's been shown to be one of the ways that people can bounce back from adversity and to move forward after bad things happen. Storytelling offers children lots of opportunities to develop initiative. First of all, their own ideas, their own pictures in their heads, and their own interpretations of those stories are what they're taking out of a storytelling session with them. That feeling as though they own the story because they've made it their own in their imaginations is one way that storytelling supports initiative. Another way that storytelling supports initiative is that the more stories that you tell in the classroom, the more stories children are going to tell on their own. Again, children telling their own stories is a fantastic way for them to take back the power that they may feel like they don't have at many other places in their lives. Storytelling provides them with opportunities for rich and engaging play and lots of different ways that they can be confident and safe in their own skins. Storytelling supports all of that.

Additional protective factors include self-regulation and executive functions. I'm sure everybody's heard of self-regulation because that is the bane of every childcare teacher's existence when kids don't have it. For example, if children don't have self-regulation, they can't sit still, can't keep their hands to themselves, can't keep from blurting out, often hit, fight, bite, and scream. We know what not having self-regulation looks like. What we need to focus on is how we as teachers can develop that self-regulation. We know that when all people are in challenging situations, self-regulation tends to go down. The development of self-regulation is much more challenging when people are encountering traumatic experiences or things that they don't understand.

How do we develop that in our safe classrooms? Storytelling is one of those ways. Children will sit through stories that they're engaged with for far longer than they'll sit with you flipping up flashcards and teaching the days of the week or any of the other things that we tend to do in circle time. Most teachers think they have to have circle time because it's going to develop self-regulation. They have to know how to sit still if they're going to go into kindergarten. They will develop self-regulation with the right kinds of experiences, such as offering circle times and group activities that support the development of self-regulation rather than work against it. If they are bored and don't feel like sitting there and they would much rather be in the block area, you are not supporting the development of self-regulation.

Executive functions are another part of neuroscience. We are not going to get into it too deeply, but it's important to know that executive functions are tied into self-regulation. Self-regulation has been shown to produce successful learning and healthy success in school as well. Another executive function is the idea of cognitive flexibility, which is being able to think outside the box to come up with different solutions for problems. Storytelling really supports that as well. For all of these reasons, and cultural affirmation, storytelling helps to support resilience.

What Stories Should I Tell?

Think of the last story you heard…

- Personal stories

- Folk and fairytales

- Favorite stories

- Class-inspired original stories

Developmental characteristics and...

- Length, complexity, rhythm, rhyme, movement…

Okay, great. You want to tell stories, but what story should you tell? To start with, think about the last story that you heard. Take a minute and think about it. Was it something that your best friend told you? Was it a TV show that you saw last night that you're still thinking about? Was it a book that you read? Whatever that is, that may give you some clues about the kinds of stories that you can tell to children. We're going to talk a little bit more about each of these, but as a way of thinking about it, was it a personal story? Was it something that somebody told you about what happened to them when they lost their keys yesterday? Was it a folk or fairy tale? Unless you're like me and watch folk and fairy tale things on TV, it wasn't that. But did it have a little bit of magic? Was there something special about it? Was it your favorite story? We tend to get hooked into TV shows or movies because we like that story. If you have favorite stories that will give you a clue of what kinds of stories you enjoy.

For kids, was it class-inspired original stories? Most of us say, "Oh, I'm not a storyteller. I could never do this." We are going to get over that hump really quickly. Once you start thinking about storytelling and the power of it, you will recognize that there are all kinds of things in our classrooms that inspire us and can be a rich source of wonderful stories.

You also need to think about the developmental characteristics of the children that we're working with. You're not going to tell the same story to a two-year-old as you would to a six-year-old. Some of those things are pretty natural. Just as you don't pick out the same books to read to very young children as to children who are a little bit older. There are some specific things about storytelling, like books, that you are going to take into consideration when you are figuring out what kind of stories to tell. This includes the length of the story and the complexity of it.

For example, if you think about the "Three Bears" it's very episodic. The same thing happens over and over and over again. There are three bears, three bowls of soup, three chairs, and three beds. That's not a very complex story compared to something like Cinderella, which has all kinds of different plot twists in it.

Understanding how children respond to the books that you read is a good idea of how to pick the stories that you want to learn to tell them. Also, think about the rhythm of the story. Stories that have rhyme are obviously for younger children. That helps a lot because it keeps them actively engaged. Is there a story that you can add in movement to increase audience participation? Those are all factors that as you are choosing stories to tell, you may want to keep in the back of your head. You know the kids in your classroom the best and you know what kinds of stories they need and where developmentally they will fit in to this continuum of stories.

Personal Stories

- Our childhood experiences

- Family experiences

- Our own mistakes and learning opportunities

What kind of stories should I tell? Personal stories are the easiest are stories we tell all the time. I'm sure you've already told a story to somebody today. We know that kids love to know us better and that hearing about what happened in our childhood is one of the richest sources of easy storytelling that you can do. They want to know what happened when you didn't like the peas that your mom wanted you to eat. They want to know what your dog's name was when you were a little kid. They want to know what you liked to dress up as when you went out for trick or treating. Those are easy stories. They're short and they will absolutely engage children and help you to feel more comfortable in your own storytelling.

Tell stories about family experiences, such as what is happening right now. Children want to know what you had for dinner last night. They want to know how many kids you have. They want to know why is it that you didn't sleep in the childcare center because you weren't here when their mommy drove them by last night and the lights were all off. They want to know about those kinds of family experiences and things that are going on in our lives right now. Kids are fascinated with and form the same storytelling culture.

They want to know that you are not perfect. None of us are. Children really know that they are not perfect. Being able to hear about mistakes that you made, learning opportunities that you had, and things that you forgot will make a connection with children that is very strong and powerful and again, supports them in the idea of becoming more resilient. It helps them see that you're okay, you're the teacher, you're all-powerful, and yet you also did something really silly like forget your keys just like their mommy did.

Folk and Fairytales

- What are folk and fairytales? 398.2!

- Easiest to learn

- Oral tradition

- Stock characters

- Simple, episodic plots

- Huge variety

- Cultural variants of many popular stories

- Magic, time aligns with preschoolers’ cognitive development

Folk and fairy tales are great to tell when you move beyond personal stories. They are another rich source. Folk and fairytales are stories that have been told through word of mouth for millennia as far as we know. You can find them in your library under the call number of 398.2. Most libraries have them in the nonfiction section.

They are the easiest stories to learn if you're learning stories that somebody else has taught. They come from the oral tradition so they were told by storytellers time and time again. They have certain characteristics that make them easy to learn. One is they have stock characters. For example, Jack is an adventurous boy. Cinderella is a kind and beautiful girl. We don't know a lot about the depth of the characters in most folk and fairytales. They are kind of like two-dimensional paper dolls that you can put your own experiences into. They really are the way that young children perceive characters anyway. They have very simple and episodic plots, so it makes it easier to remember. You have that story structure in your head already so it fits right in with what you're expecting a story to be.

There's a huge variety of them. There are over 1,000 different cultural variants of Cinderella. Think about how many different variants there are in our American culture and how many different picture books you've seen of Cinderella. The stories can be framed in many different ways. There's a vast variety so you can pick which ones will go best for which group of children. Many of these come from all over the world as we've been talking about. If you have a child in your class that just came here from Mexico, you might choose Adelita, which is a Mexican Cinderella story. There are a lot of different plots. Some are long, some are short, some are scary, some are not. Through sharing lots of different versions of these stories with children, you can help them to connect with culture as well as with story structure and all of these other great literacy things that we've been talking about.

The other reason that I think that folk and fairy tales are uniquely perfect for young children is that most feature magic, whether it's magic, magical things that happen, or magical characters or talking animals. All of these align with young children's cognitive development. We know that kids believe in magic. John Piaget, one of the firm foundational grandfathers of our field talked about magical thinking in young children.

It is characteristic of preschoolers that until they become more sophisticated in their cognitive development in the early elementary school years, young children have a belief structure that aligns with magic. They don't have a good sense of time. Ask any preschool-age child, "When's your birthday?" and they'll usually reply, "It's today," even if it's today, tomorrow, in the future, or yesterday.

Fairy tale time is the same way. Once upon a time... They lived happily ever after. There's no strict sense of time. We as adults may wonder how long Hansel and Gretel wandered in the forest. Was it for an hour or was it for a day? Was it for 10 weeks? How long did it take them to get to the witch's house? Young children don't ask that because they don't have a sense of time that we have. Folk and fairy tales are a perfect match for young children and mesh with their cognitive development beautifully.

Favorite Books

- Importance of loving the story

- Repeated and varied readings/tellings build fluency and depth of understanding

- Using puppets, flannel boards and other props

You might not feel comfortable telling folk and fairytales. Instead, think about what some of your favorite books are. Children's books are a wonderful source of stories that you can tell without the book. Do you love the book? If you love it, then it's worth giving it a shot and seeing if you can tell it.

We know from research that repeated and varied tellings and readings of the same story build fluency and understanding of the vocabulary, the story structure, and the characters. The children deepen their understanding every time they hear a story. There is an idea that we should read a story on Monday and a different one on Tuesday and a different one on Wednesday. All the research says, forget about it. Think about your own kids. If you have children at home, they want to hear the same story over and over and over again. In the classroom, we can do the same kind of thing. That's why we may want to be able to tell stories that we've already read to children and just tell them in a different way.

You can use puppets, flannel boards, and other props as you tell the story. After you've read the book to the children, you might want to take the book out of the picture and continue to tell that same story to children in different ways.

Class-Inspired Original Stories

- Routines

- Discoveries

- Conflicts

- Challenging behaviors

- Vivian Paley

You can tell class-inspired original stories. One example is stories about routines. Who hasn't had trouble with cleanup time? Here's a story about cleanup time.

There once was a little girl who never wanted to help clean up. Then the ice cream truck came outside of her house and she heard the dinging of the ice cream truck and she had to try to jump over the blocks and jump over her dolls. She crashed into the dump truck that her brother had left on the floor and fell over the ball that she left by the door and the ice cream truck went away. She didn't get ice cream that day.

A story like that when you're having trouble with cleanup is far more effective than saying, "I can't believe that we're still trying to clean up this classroom after 15 minutes." Kids respond to stories. They love stories and they live in stories. Use them to support your routines.

Tell stories about the discoveries that they make in the classroom or outside. Tell stories about what they are learning about? Conflicts are inevitable and occur all the time. We know that conflicts and challenging behaviors are part of our early childhood classrooms. How can we use stories or storytelling to help kids look at the conflict or the challenging behavior in a different way?

Vivian Paley is one of my heroes. Her books are filled with examples of how she's taken children's classroom behavior, framed it in a story, and been able to work through it with her classes. She talks about how a problem can be solved or how to support a child not doing the things that they're doing. If a child is kicking over the other children's block buildings by mistake, do children understand it's a mistake? They may not understand intentionality. However, you could tell a story about the little boy who was born with big, big feet. One day he saw his friend's castle and he went up to look at it. All of a sudden his big feet knocked down the castle and his friend got really, really mad. But what happened to the little boy? He couldn't help it. His big feet bumped into the castle. Helping children to understand motivations and intentionality can go a long way in addressing the challenging behaviors that might be in your class.

How Do I Learn the Stories?

- Memorization NOT needed!

- Five readings to make it yours! *

- Enjoyment: Do you even like it? Why?

- Characters: Who’s in this story? What do they look like, sound like, smell like, etc.?

- Catchphrases: Including beginning and ending, songs, rhymes, magic words, etc.

- Environment: What does the house, the castle, the forest look like, sound like, smell like, etc.? Can you see yourself there?

- Confidence!

- PRO TIP: Children will love it even if you forget things!

- Use Making a Story My Own in 5! handout to help!

How do you learn the stories? Obviously you know your personal stories and you can just tell them. The important thing to remember is that you don't have to memorize stories. There's a handout called Making a Story My Own in 5! you can download and use. Hopefully, that will help you realize that professional storytellers said you can make any story yours in just five readings. If it's a short story, maybe three readings.

Five Readings to Make It Yours

Here's the process. The first time you read it is for enjoyment. Do you like it and do you enjoy the book? If you don't enjoy a story, then why bother telling it. If it's a no, then move on to the next book. If it's a yes, then move on to the second reading. The second time through, focus just on the characters and things such as:

- Who's in it?

- What do they look like?

- What do they sound like?

- What do they smell like?

- Are they nice or are they not nice?

- Do you like them?

Just focus on the characters and get to know them. Think about when you're reading on your own and how you connect with certain characters in a book and you don't connect with other characters in a book. You know and you see those characters. You want to do that the second time through a story reading.

The third time through focus on catchphrases such as the beginning of a story or the ending so you can get in and out easily. Other things to focus on include any songs, rhymes, or magic words that might be included. Those are things that you might want to jot down so that you can feel confident as you're telling the story.

I once told the story of Rumpelstiltskin after having not read it for a while. I got all the way to the part where he's dancing around the fire in the forest and I realized I had no idea what the song he was singing was supposed to be. I knew that it had to rhyme because it was his name. I thought, "Oh no, what am I supposed to do?" I quickly made up something that didn't really rhyme, but I got the Rumpelstiltskin out and the kids didn't care. They either didn't know or they didn't pay attention. It was a good reminder to me that next time I might want to write down things that I want to say exactly the way they were said to help me remember. Once upon a time and happily ever after are classic beginnings and endings of stories. This is because it gets you into the story and it gets you out of the story. You'll feel more confident when you know how you're entering and leaving a story, even if in the middle you make it your own and change things around.

The fourth time through focus on the environment. What's it like? Is it a deep forest? Is it a big house or is it a tiny cottage? Imagine all of those aspects of the environment and just focus on that the fourth time through. You already know the characters and you've got the catchphrases down.

That brings you to the fifth time through. This time you're just reading for confidence. You know this story by now. Read through it and anticipate what's coming next. Imagine it in your own mind's eye and you'll be ready for prime time and to tell kids some stories.

Pro-Tip: Kids will love it even if you forget things, as I just shared. They often don't know or they don't remember. They just want to hear the story and they want you to be telling something to them that you care about. Remember, you can use the handout as a worksheet and scribble ideas down on it if you want.

How Do I Tell the Stories?

- Key elements

- Focus and eye contact

- Voice

- Gesture

- Pacing

- Audience participation

- Props, costumes, puppets, etc.

How do you tell stories? Storytellers talk about the key elements, including focus, eye contact, and voice. Are you going to change your voice? Are you going to do it loud or soft? Other key elements include gesture and pacing. How fast or how slow will you tell the story. Of all of these, your focus and eye contact are the most important because that's what establishes the relationship and connection with the people who are listening to your story. The rest of it is really up to you.

I'm a very loud and animated person. I always talk with my hands. It doesn't matter what I'm talking about, my hands are always going. That's my storytelling style. However, Miss Sally, who was one of my beloved teacher mentors when I was a very young teacher, told all of her stories with a quiet voice. She kept her hands folded on her lap and never raised her voice. That was her storytelling style. Finding your own storytelling style is the most important thing with all of these other elements of storytelling. Make it your own, but keep the focus on the children or adults that you're telling stories to.

You can use audience participation. Young children will often participate even if you don't invite them to. Be ready for that. If you pretend you're cold and are running and running and running up a hill, watch the children's hands running and running and running up the hill, even if you don't invite them to. Encourage that because that's taking the story and putting it into their own context.

You can use props, costumes, puppets, and all of that kind of stuff. I don't use that much because I'm kind of a klutz and I stick the fairy godmother's wand in my eye when I try to use it. Again, make the storytelling your own. There are so many different kinds of storytelling. Find something that works for you and the children that you're working with.

Storytelling in the Classroom

- Storytelling and Standards

- Storytelling and the Schedule

- Circle Time

- Transitions and Routines

- Centers and Small Groups

- Outside

- Children’s Storytelling

Storytelling aligns with all the standards. Check out the early childhood standards in your own state and you'll probably find many ways that storytelling aligns. You can use storytelling throughout the whole schedule. Don't forget children's storytelling because that's when you really know that children have taken your own storytelling and turned it into powerful storytelling that they can do themselves.

Standards

Every state has different standards. I'm not going to get into the detail, but when I went through our standards for Pennsylvania, where I live, and looked for connections between the standards and storytelling, I found the ability to connect storytelling to every single one of the content areas. Storytelling connects to reading, writing, speaking and listening. It also connects to movement in the arts. How many times do we tell a story and then have children go and create some art related to it or dance a dance that's related to it?

We're telling them stories from all over the world and talking about families and communities, which addresses social studies standards. Whether they are magical families or the families that are in your community where you live, children make the connection to families and community helpers. All of those are found in any story that you might tell. The social-emotional aspect is huge. We've talked a lot about that already.

It might be hard to imagine how you're going to tie storytelling into math, but I'm sure you all remember the math story problems from when you were in elementary school. We're not going to torture children with them, but we can easily work math into the stories that we tell. Storytelling also connects to the standard of approaches to learning through play. They hear it and they play it. It's problem-solving and risk-taking. There are many folk and fairy tales and stories that you can tie into your science curriculum as well.

Daily Schedule

How do you tie it into your daily schedule? I've given you lots of examples of that. Circle time storytelling is usually far more engaging than reading a book, especially to larger groups of children. They don't have to see the pictures because you're the picture. In their heads, you're the pictures instead of the book.

Use storytelling during transitions and routines. Help little ones who are out taking a walk by supporting their understanding of why it's important to stay out of the street. For example, use a story about a bunch of little ducks who walked across the street until they saw the penguin flashing his hand saying, "Stop, stop, stop." They knew they should not walk into the street because it was dangerous. That is much more effective than just saying, "Okay, kids stop."

You can tell stories in centers and small group time. Tell stories about things that you've put in your centers so that children will continue to play. Outside on the playground, storytelling can happen anywhere and everywhere. It's just a matter of freeing yourself up to realize that what you're doing has so many positive benefits.

Children's Storytelling

- What is it?

- Vivian Gussin Paley

- How do I do it?*

- What do the children get out of it?

- Use the Storytelling/Storyacting the Vivian Paley Way handout as a guide to get you started!

Children's storytelling and story acting were created by one of my heroes, Vivian Gussin Paley, who has written 13 books. They are all listed in the handout called Links to Storytelling Resources. Her idea was that children would tell a story and an adult or an older person (this could be an older child) would act as a scribe and write down the story exactly as the child says it. You do not fix the words or add anything. You can ask clarifying questions, but basically just write down what the child says. It sounds like something we all have done when we had to take story dictation.

Paley said the next step of that is then to give the children an opportunity to act it out. Bring the children into a circle and the author of the story gets to pick out what character they want to be in that story. The teacher picks out the other children who will be the other characters. You could have children be characters, trees, rabbits, cats, benches, or anything else. The goal is for kids to have good imaginations. Then as the teacher reads the story, the children act it out and the rest of the children watch and participate as an audience. It has been found to be an extremely powerful way to not only connect children's oral language to the written word because it's their words but also to build community, to build social and emotional awareness, and to help them understand self-regulation skills.

It builds self-regulation skills because they are sitting in the story and they find their own stories and the stories of their friends much more interesting and engaging than anything that we could come up with. As they tell their stories and do it repeatedly, their stories become more complex. They integrate ideas of story structure and they become readers and writers in this storytelling story acting context.

There's a handout called Storytelling/Storyacting the Vivian Paley Way that I came up with to help you understand those steps if you're interested in trying this strategy in your classroom. The more stories you tell, the more kids will tell their stories and it all ties in together beautifully.

Closing

In closing, think about one way that you can use the ordinary magic of storytelling in your class today. I encourage you to jot down a few things so that you can remember and just try one thing. Is it going to be to talk about what you did over the weekend in circle time instead of asking about what color everybody shirt is? It can be something as simple as that. Thank you so much for playing with me today. I hope that you have wonderful storytelling adventures. If you want to know more about storytelling, there is a handout with a big list of references and websites about storytelling and places you can go to get more information.

References

See handout.

Citation

Goloway, S. (2020). The Ordinary Magic of Storytelling. continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23554. Retrieved from www.continued.com/early-childhood-education