Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Preventing Challenging Behaviors, in partnership with Region 9 Head Start Association, presented by Julie Kurtz, MS.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe the difference between sensory and emotional literacy.

- Identify 1-2 strategies to help children identify whether their emotions are small, medium, or large.

- Identify 1-2 strategies to engage children in building self-regulation tools to manage their big emotions.

- Name and identify 1-2 strategies to teach children emotional literacy.

Introduction

I'm so happy to be here and I'm so grateful for educators that are willing to take the time to reflect, build self-awareness, and have a growth mindset and not land on saying to themselves, "I already know everything. Why do I need more of this?" I'm 52 and I've been on this journey and I keep learning and growing. It's so amazing because we have this great responsibility to grow humans to be humane. Preventing challenging behaviors is one of the biggest struggles for educators and people who are working with young children. Today we're going to talk about how we prevent challenging behaviors and how we help children when they do have challenging behaviors. We will also talk about the meaning of challenging behaviors. What is the meaning of all of this and why does it have to happen?

A Child's Brain is Like an Iceberg

A child’s brain is like an iceberg. What do I mean by this? Most of what we see and are faced with is the tip of the iceberg, which is the child's behavior. That's often what we see and what we react to. But underneath that iceberg are depths and depths and depths of what's happening inside of that child. Many people, myself included, were raised to cast the spotlight of our attention outward rather than inward, all the way up to age 18.

For example, think about Jeremy, a seven-year-old boy. If we walked through a day in his life, from the moment he got up to the moment he goes to bed, my prediction is that 95% of that day, the caregivers, adults, teachers, and educators are casting the spotlight on that child's attention outward. Examples include:

- Why did you do that?

- You need to eat more protein.

- Did you pack your bag?

- I got an email from your school that you didn't finish your homework.

- Oh my goodness, we have a pop quiz now!

- Who should I play with on the playground?

- You gotta go to the dentist.

- You gotta go to the soccer game.

- Stop fighting with your brother!

- You need to clean the dishes.

- You need to do this, you need to do that.

- Why aren't you getting your homework out?

- I'm going to take your video games away.

All day, we are directing and correcting, and casting the spotlight on a child's attention outward. Then that child grows up into adulthood and is ill-equipped to hold a job, to handle difficult relationships, and to have a relationship. All because there's this entire universe that lives inside of you, filled with emotions, sensations, and feelings. They're small, medium, and large throughout the day, like a roller coaster.

When we're not aware of this universe that lives inside of us, it can take over and hijack us to do things that often hurt others, ourselves, and property. That's true for adults and for children. We have to look a little deeper at a child's brain and behavior and say to ourselves, I am not going to just look at the tip of the iceberg, which is their behavior. I'm going to look at what is underneath it, the meaning of their behavior. I'm also going to help the child by casting the spotlight underneath the iceberg, the outer world, into the inner world.

I know that as an adult, one of my responsibilities is to teach children these four steps to prevent challenging behavior. We'll go over these more in-depth, but I'll just mention them now. Step one is teaching sensations and emotions. Step two is teaching when those sensations and emotions are small, medium, and large. Step three is helping children build a grand self-regulation toolkit. When you're a baby, it's your parent who self-regulates you and your thumb, pacifier, bottle, or fingers. Then as you get older, you get a teddy bear, a blankie, and your bed. As you grow up, you start to develop a greater self-regulation toolkit until you've got such a big toolkit, you can manage your emotions and not be hijacked by them. The fourth step is being able to problem solve and think things through. Now let's move beyond the tip of the iceberg and look at the whole child.

Brain Architects

If I were the queen of the whole universe, I would change all educators’ job descriptions and include that you're a brain architect. A brain architect means that you are directly influencing the growth of a child's brain, both internally and externally by the things that you do. If you're a brain architect, you have a recognition that between the ages of zero and six years old, the child's brain is growing one million neurons per second. No, you didn't read that wrong. One million neurons per second. The brain grows more between zero and six years old than at any other time in their life. You have such power to support the architecture of the brain to be healing and healthy or not. Your job description is critical. One of the ways that you can be the best brain architect of growing humans to be humane is to say to yourself, challenging behavior is merely communicating a story or a need. This might be one of the following.

- To gain someone or something

- To avoid someone or something

- To express a sensation/emotion

I want to share a story with you about a day I was so angry at my husband. This happened when my kids were little and they are now in their mid-20s. I can remember the day where he was so involved with all my kids’ sports activities and work and community events. He was casting the spotlight of his intention everywhere except me. I didn't realize this, but I had a tea kettle effect happening inside of me. My emotions were bubbling up from green (calm) to orange (medium), to red, when they started steaming and the tea kettle started to scream. I woke up Sunday morning and part of the cause of the bubbling of emotions was that I wasn't getting any attention. I didn't know it at the time, but I felt unloved and I felt neglected. I woke up Sunday morning and I purposely burned his breakfast and then I flushed the toilet when he was in the shower to make the water go cold.

Now, is this healthy? No, this is not a healthy way to communicate that I need love and attention. But even as adults, our challenging behavior is communicating a story. If my husband came back to me and said, "Why are you acting all crazy? Why'd you burn my breakfast?" I would get more triggered. What would be better is for him to say I think that you're trying to communicate something to me.

But most of the time we don't do that. Children have immature brains. It takes 25 or so years to grow a human to be humane with a fully integrated brain, where all the parts are talking to one another. We can expect that a child's job description is to have challenging behavior, at least up until they're 25. If it's their job description, it's our job description as a brain architect to say to ourselves, ah, when this child has challenging behavior they're communicating something to me.

Can you guess what I was communicating to my husband? Was I trying to gain someone or something? Was I trying to avoid someone or something? Was I trying to express a sensation or emotion? Pause for a moment and think about that.

If you guessed that I was trying to gain someone, that's right. I was trying to gain attention and connection. I was also trying to express an emotion of sadness, hurt, and neglect. He wasn't intentionally doing these things but if we want to be healthy adults, we would be able to tune immediately and say instead, I need attention. I feel like I'm being neglected. We need time together. I need love and connection.

If we were all raised to teach kids these four steps and if we were raised to identify how small, medium or large our emotions are, then I would have a better chance of tuning in to my own self and communicating in a healthy way. We have a chance to teach this to kids.

In summary, as a brain architect, we need to determine what the meaning of a child's behavior is, underneath that iceberg. The tip of the iceberg is the behavior and underneath the iceberg, the child is trying to gain someone or something, avoid someone or something, or express a sensation and emotion. Remember to pay attention to the fact that not only is behavior communicating something, but you have to be a brain architect and an investigator, which makes it really hard.

When my kids were little, I just wanted to push their belly button, have the printout come out and say, I'm trying to avoid doing this chore. I'm trying to avoid circle time. I'm trying to gain a connection with you because you've been so busy. I'm angry because they took my toy. We're not only a brain architect but now we have to be an investigator and observe children's behavior.

The last thing is to not punish or bribe with rewards. This might push your emotional buttons a little bit to hear this, but I ask you to just sit with it and think why. When you punish, yell at a child, or criticize them when you are witnessing their challenging behavior, it causes them to be more scared, more terrified, and it doesn't teach.

We Need to Teach

We need to teach. Let's think about this a little bit more. Tom Herner (1998) said,

“If a child doesn’t know how to read, we teach.

If a child doesn’t know how to swim, we teach.

If a child doesn’t know how to multiply, we teach.

If a child doesn’t know how to drive, we teach.

If a child doesn’t know how to behave, we…….....

Why can’t we finish the last sentence as automatically as we do the others?”

If a child doesn't know how to read, what do we do? We teach. If a child doesn't know how to swim, what do we do? We teach. If a child doesn't know how to multiply, we teach. If they don't know how to drive then we teach. But for some reason, if a child doesn't know how to behave, we tend to do something else and that's punish. Instead, we want to teach. Social-emotional skills must be taught to children. It's not a skill or something that you're born with.

It's difficult to finish this last sentence because when children have challenging behaviors, they push our emotional buttons, and then our emotions rise up from green (small), orange (medium), to red. When the red goes off, it activates a built-in smoke detector inside of our brain called the amygdala. When the smoke detector goes off in the adult's brain, it sends signals down to a lower part of our brain called our survival brain or our reptile brain that makes us want to fight, flight, or freeze.

When our smoke detector goes off and our emotions rise up to the red zone, we want to punish to make it stop. We want to yell at children to make it stop. We want to bribe them to make it stop. We want to give them that candy bar to make it stop. But none of those things build that optimal brain integration, that ability to learn how to problem-solve and regulate and teach.

Teaching social-emotional skills proactively, when children are calm, is what is actually going to prevent challenging behaviors more often. Challenging behaviors are a child's job description. Teaching is our job description. That, quite frankly, is the way that we will prevent challenging behaviors.

Now, let's pause for a moment. Growing up in California, we had earthquake and fire drills when I was a child. Some of you may have had other emergency drills, such as hurricane or tornado drills, based on what types of emergencies you have in your state. Now more and more in our country, it's shootings that we get worried about as well. The reason why we do drills when the child is calm is to secretly wire one neuron to the next neuron through practice.

Did you know the brain doesn't know the difference between practice and real life? When you practice a skill with a child, you're wiring the brain. One floating neuron connects to another floating neuron and wires. The more you practice, the wiring becomes stronger. Dr. Daniel Seagal says that neurons that fire together wire together. So the more we practice with children and teach them social-emotional skills, the more they'll default to that habit in a real and emotional emergency.

The other thing that we have to pay attention to is every child has an invisible voice recorder inside of them. What we say to them and the way we talk to children becomes their inner voice. This invisible voice recorder is really powerful. I know that my dad criticized me all the time growing up and my internal dialogue after I left my family, was very negative about myself. I would beat myself up easily. I would think negative thoughts about myself. It took a lot of years to rewire this inner recording that came from my dad.

We have to think to ourselves if a child has an invisible voice recorder inside of them, what do we say to them? The research shows that we correct and direct or criticize children when we're faced with challenging behavior. Sometimes we just criticize and direct throughout the day five times to every time we give a positive or a neutral statement. That means most children grow up and are raised with an internal voice recording that's negative. That in turn, impacts what they say to themselves and their behavior.

I wrote an article called "Nutritional Praise Versus Sugar Praise" which talks about giving praise to children. Sugar praise is when you say, "Good job, I like the way you did that." That's not bad. It’s actually wonderful that you're acknowledging something positive about the child. Keep doing that. Our brains are designed to scan for the negative. Many who lived in primitive times in tribal villages saw rainbows and unicorns and didn't ever see the danger. Their brain was wired to see the positive and they were more likely to die, eat poisonous plants, or be pillaged by the local tribes. Our brains still have not evolved to scan for the positive. This is even more work. We actually have to make this a part of our practice, to scan for children's positive traits.

What's the difference between sugar praise and nutritional praise? Nutritional praise is when we give more information. Here are some examples of nutritional praise.

- Sweetie, you gave your friend a tissue when they were crying, that was being so friendly.

- Oh my goodness, you pushed your chair in after you ate. No one's going to trip on it. That's being so safe.

- You sneezed in your elbow, that was being really healthy. You're not going to spread your germs.

Throughout the day we can describe more specifically not just what we observe the child doing, but the why behind it. The child begins to internalize that when I did this, I was friendly. When I did this, I was respectful. Then their internal voice becomes one of self-efficacy, self-esteem, and one with a more specific internal dialogue rather than I did a good job or I should do that because that parent likes it or that adult likes it or that teacher likes it.

Sugary praise is not bad, it's fine. You can always say hey, Maria good job! Then add the why behind it after. When you brought your papers to the front, you were being so respectful. Those kinds of examples would be adding on at the end of good job. Remember, the way we talk to our children becomes their inner voice.

Four Steps to Teach ALL Children

Today you're going to learn four steps as a brain architect to teach children and grow them to be humane.

- Identify my sensations and emotions.

- Identify how small (green), medium (orange), or large (red) sensations and emotions are in my body.

- When my sensations or emotions are in the orange or red zone (medium/large) then I have to pick a self-regulation strategy to manage and calm my big emotions.

- Think, think, and think of a solution to my problem.

Identifying sensations and emotions is the first one. The second of four steps to teach is helping children identify when those sensations or emotions in their body are small (green), medium (orange), or large (red). This is very complex. The first step is to learn all the feeling and sensation words. The second step is to identify when those are small, medium, or large inside of me.

The third step is when they have identified that their sensations or emotions are in that orange zone or red zone, they have to pick a self-regulation strategy to calm their red zone down to the green zone. Because if they act on their red zone, they always hurt others, themselves, or property. One of the things we want to support kids in is if they can recognize they are in the orange zone, they need to pick a self-regulation strategy out of their self-regulation tool kit. This will help children be more apt to calm themselves down.

The fourth and final step to teach all children is to think of a solution to their problem. When I say all children, this includes children with histories of trauma, children with special needs, children with mental health vulnerabilities, and children who are typically developing. The last step, once their brain and emotions are calm and their sensations are down to green again, is teaching them they can then think, think, think of a solution. That involves practicing over and over the different types of solutions that don't hurt themselves, others, or property.

Step 1

Identify My Sensations and Emotions

Let's talk about step one, helping children identify their sensations and emotions. Sensory and emotional literacy is the ability to identify sensation emotion words, identify sensations and emotions inside me, and identify when sensations and emotions are small, medium, or large.

Now let's try to understand, through the grid in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Grid explaining how children can identify their thoughts and emotions.

The far-left column is titled trigger. It's a triggering event that triggers our emotions and could be a trauma trigger or reminder. It could be an emotional trigger. For that child, it's a trigger. An example of a trigger is a stranger entering the classroom. I'll never forget the time when I walked into a classroom and they didn't introduce me. The child came up to me and asked me who I was and I told him. He said, "Did you see that spider over there? I hope he eats you up and makes you dead." This is an example of a child who was triggered by my presence. I was a stranger and to him I represented danger. Let's look at what can happen inside the brains and bodies of a child when the stranger walks into the class and there's a trigger emotionally for them.

The second column is about sensations. Sensations are when you feel stressed or your body physiologically sends you a clue. Your stomach hurts or is nauseous. Your heart starts racing. You feel like there's a volcano inside of your head. Maybe your head starts pounding, your jaw starts clenching, or your hands and palms are sweaty. These are sensations. For this child, they had butterflies in their stomach. That was the sensation. The third column is about emotions, followed by the thoughts children may have from these emotions. This child had the emotion of fear and then was triggered with the thoughts, oh my God, they might hurt me.

This is what is underneath the iceberg. The triggering event is the stranger entering the class but we don't see that. The sensation is what's happening in the child's body and maybe all we see is that they have their hand on their stomach. With the emotion, fear, maybe all we see is their facial expressions or their fists clenched. We often don’t see the thoughts, such as they might hurt me. The only thing we see is the triggered or challenging behavior. When we only react to the challenging behavior, rather than the story that's happening underneath the child, we're missing a big opportunity to help them use their words, help name what they're experiencing, and help to co-regulate and calm them down and feel safe again so that they can think more clearly.

Let's look at the next example where the triggering event is nap time. You announce to your classroom, "It's nap time!" For this particular child, the sensation in their body is more frozen, like an ice cube or an iceberg. It feels like their feet stop moving and they have no thoughts or words. They can't move and they become immobile. The emotion they have is scared or frightened. The thought this child has might be I'm not safe and someone may hurt me if I sleep. All we see as adults is the surface or the tip of the iceberg, which is this triggered, challenging behavior.

When all we do is react to the challenging behavior with threats and bribes, we not only don't teach, but we can scare the child more. Also, we don't seize the opportunity to be brain architects by turning them inward. Here’s an example. Sweetie, I see that your body looks frozen right now. I'm wondering if you're scared? I want you to know that you're safe and there's nothing dangerous. I'm going to sit here with you until you fall asleep. Then I'm going to be here when you get up and we're going to have a snack. When we do things like that, we help the child feel safe again and we help to co-regulate them. The strategy that I just used is a strategy that addressed the part underneath the tip of the iceberg. Those are the things we can't see but we can guess.

There's a difference between sensations and feelings. When sensations or feelings are triggered by an event, there's a release or charge of energy that happens within our body. In fact, when we have emotional buttons pushed, we release toxic stress chemicals to the hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis, which sends stress chemicals through our body. This tells us we need to fight, flight, and freeze and also sends messages that we're not safe and we're in danger.

One of the ways that our body expresses this charging event is through sensations in our body. These are physiological happenings in the body due to the energy charge the body experiences or feels. Examples include my head hurts, I have a pit in my stomach, my palms are sweaty, or I'm shaky. Your body is really communicating the intensity of that experience.

Feelings are the words that describe how you feel. As I said, they can be mad, angry, frustrated, or sad, but they can also be small, medium, or large. They are also triggered by an experience.

Figure 2 is from our book, Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators. It shows and explains sensory language versus feeling language.

Figure 2. Sensory language versus feeling language.

Sensory language is in the left column and feeling language is in the right column. It is helpful to teach kids sensory language as well as feeling language so they can recognize the sensory symptoms in their body as a clue that they might have a button pushed. Examples of sensory language include:

- Does it feel like butterflies are in your chest?

- Does it feel like bumblebees are buzzing in your stomach?

- Do you feel jumpy like a frog?

- Do you feel slow like a turtle?

It's tuning them into the body sensations and feeling language such as scared, anxious, nervous, panicked, stressed. Those are language words that identify emotions. We want to teach children both.

Encourage Sensory Recognition

One way we can encourage sensory recognition is to tune children into their body sensations. You might notice a child's face is all scrunched up, their fists are clenched, or they are rubbing their eyes. When my children were young, my partner sometimes wouldn't read those clues so he would keep wrestling with them or playing with them. Then they would go over the top of being overstimulated.

Sometimes it's really important to read the physiological clues because that's all we're getting. But we can help tune children in by saying it looks like your body may be tired. When that happened to you, I saw you holding your stomach. I'm wondering if it feels like a volcano or bumblebees in your stomach. Help them pay attention.

Sensory Practice

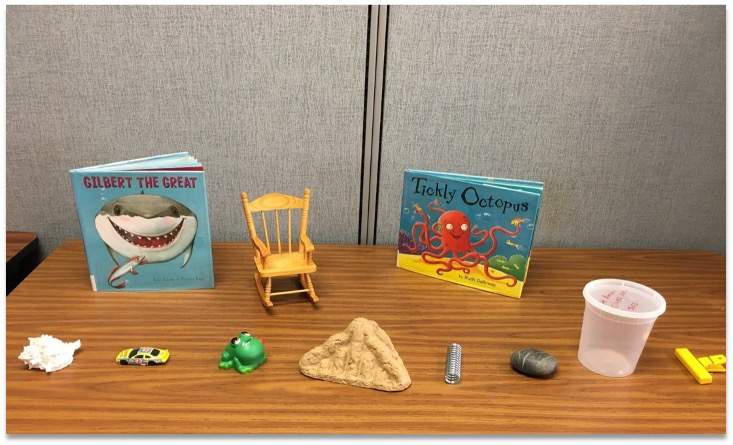

A teacher named Lakshmi at the Deansa Child Development Center came to one of my trainings. She implemented this sensory practice and sent us the image seen in Figure 3 to show some of the items she used to help children with sensory practice.

Figure 3. Items used during sensory practice (photo courtesy of Lakshmi).

Lakshmi told the children, "Oh children, we have been learning about feelings. Now we're going to learn about sensations in our body connected to those feelings." She pulled out a bin filled with objects (as seen in Figure 3). She said, "Do you see this shell? Sometimes our body feels prickly inside. Do you see this race car? Sometimes we feel like racing away or running away. It's like flight. Do you see this frog? Sometimes we feel jumpy or like we're jumping out of our skin. We can't sit still. Do you see this little mini-rocking chair? Sometimes we feel rocky and shaky."

The brown cardboard material in the photo came on the corner of a television when it was purchased. It's like a lumpy and bumpy piece of cardboard. Sometimes we feel lumpy with bumps inside of us. Do you see the twisted coil without sharp edges? Sometimes we're all twisted up inside. Do you see this heavy rock? Sometimes we feel like heavy rocks are on our shoulders, head, heart, stomach, and feet. What about this empty container? Sometimes, this is like a freeze and we feel nothing. Do you see this little chip clip, children? Feel it on your finger. See how it's tight? Sometimes we feel tightness in our bodies.

Then, teacher Lakshmi would read Gilbert the Gray and Tickly Octopus. She would have a feelings face chart and ask the kids to guess what the characters were feeling. She would then pull out a sensory object for kids to guess what sensations they might have in their bodies. Over time, she could expand that learning for the children, to wonder when they had that sensation or that feeling. This is a wonderful example of promoting sensory awareness, emotional awareness, and body awareness.

Teaching Sensory Language

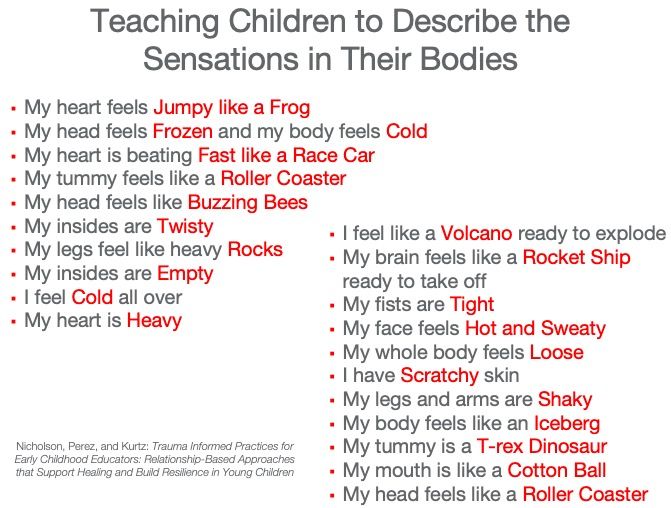

There are several examples of different ways you can teach kids sensory language. Figure 4 shows different phrases to teach children to describe the sensations in their bodies.

Figure 4. Phrases to teach children to describe the sensations in their bodies.

These are examples of helping kids use visual images they're familiar with to name the sensations in their bodies. My tummy feels like a roller coaster. My insides are twisted. I feel cold/hot. My heart is heavy. My brain feels like a rocket ship. My fists are tight. I feel sweaty. I feel like my mouth is like a cotton ball.

Resources

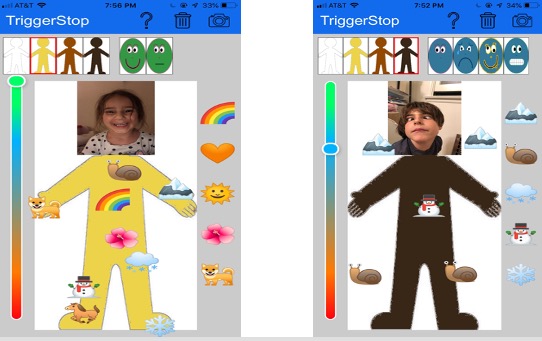

I have created an app called Trigger Stop: Sensory and Emotional Check-in that is for children who are developmentally ages three to eight years old. At the top left of the Trigger Stop app, you can see the two photos seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Trigger Stop: Sensory and Emotional Check-in Application.

These are my nephews in the pictures. I've gotten permission from their parents to use these photos. At the top left, the child can choose the color of the body that they want. They can be white or yellow or brown or black. The child can move the thermometer on the left from green to blue to orange or red. Green represents feeling calm, regulated, cool as a cucumber, flexible, and easy-going. Red represents the opposite end feeling angry and upset. The feeling faces are seen at the top next to the body choices. The child can drag the cartoon feeling faces to show you what they're feeling. There's also a camera icon and the child can take a picture of their face to practice when they're calm, making those different feeling faces.

In the image on the left in Figure 5, at the top right side of the body are sensory images that represent that green zone, including rainbows, hearts, suns, flowers, and puppy dogs. As you move it to blue, you get freeze images as seen on the image on the right in Figure 5, including icebergs, snails, clouds with ice chips, Frosty the snow person, and a snowflake. As you move it to orange, it represents flight. Flight is like a roller coaster, a jet plane, a rocket ship, a little child riding away on a bicycle or in a race car, or a horse galloping away. The red zone, those big emotions of fight, have images like dinosaurs, explosions, lightning bolts, volcanoes, and flames of fire.

The child can communicate to you their feelings and what sensations they are having in their body either verbally or nonverbally. They can also take a photo of their own feeling face. The best way to use this app is to proactively practice with children when they're calm. Read books and have them guess what the characters might be feeling. Over time, the child will actually use the app and you can prompt them to use the app to communicate with you.

Another wonderful resource is Gabi Garcia's book, Listening to my Body. This is one of the very few books I see out there that teaches sensory and emotional literacy to kids about three to eight years old. It's a wonderful book. It also tunes kids inward to listen to their bodies. This includes their breath, heartbeat, what their muscles or belly are feeling like, their energy level, and the temperature of their skin. There are practice activities at the bottom of every few pages where you can practice with kids. For example, rub your hands together for 15 seconds right now. After you stop, what do you feel? Did you guess tingly or warm? That's one of the activities in the book that helps kids tune in to sensory language. I highly recommend this book for teaching sensory and emotional literacy.

Emotional Literacy

We need to introduce kids to feeling charts but only introduce to them one to four feelings at a time. One classroom I visited had kids check in on how they were feeling. Figure 6 shows the chart that children used.

Figure 6. Feelings check-in chart (from www.cainclusion.org).

The children’s names are on the side of the poster, although you can't see them in this picture. Every morning with their parent, the children talk about how they're feeling and choose which feeling face to put their name under on the chart. Throughout the day they get to move their name card when their feelings change. It’s important to teach kids that feelings change, they don't stay the same.

Another way to teach kids emotions is to wonder how the child is experiencing their affective state at that moment. For example, I wonder if you feel sad right now. It appears you might be frustrated. We want to try to stay away from saying, "You're mad. You're frustrated." Instead, take a wondering stance and see if we can get them to validate it.

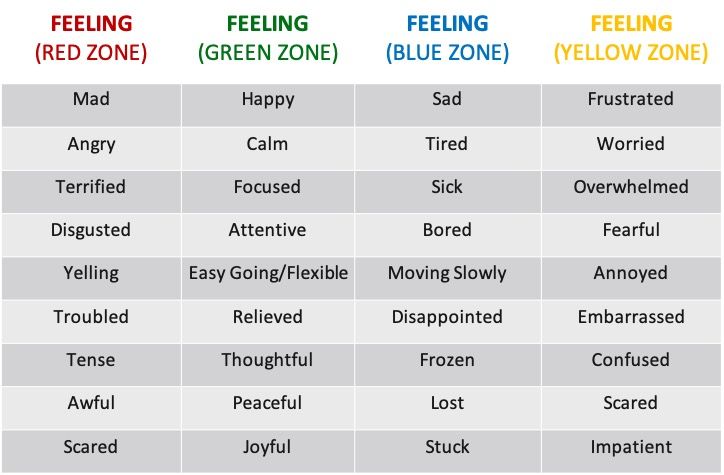

Figure 7 shows a chart based on Leah Kuypers’ book, The Zones of Regulation. This book introduces feeling language including terms for red zone such as mad, angry, terrified, disgusted, and scared.

Figure 7. Feelings language chart.

This book introduces feeling language including terms for the red zone such as mad, angry, terrified, disgusted, and scared. The green zone is happy, calm, easy-going, joyful, and peaceful. The blue zone is kind of when you get down and stuck and frozen, like sad, tired, sick, bored, or moving like a snail. The yellow zone is more like frustration, worry, scared, annoyed, confused, impatient, and on edge. This is another way to introduce feeling language to children. This option is geared more to older children. It is really valuable to see different ways we can introduce feeling language.

Step 2

Identify Whether Sensations and Emotions Inside Me Are Small (Green), Medium (Orange), or Large (Red)

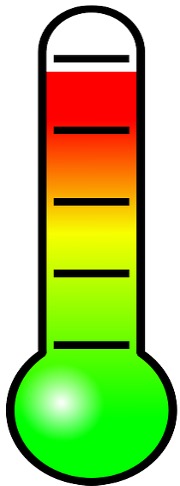

Step two in our four-step process is to identify whether sensations and emotions inside of me are small like a mouse (green), medium like a cat (orange), or large like a lion (red). Introducing a feelings thermometer like the one seen in Figure 8 can help kids identify whether they are in the green zone, the orange zone, or the red zone.

Figure 8. Feelings thermometer.

Orange means “emotions are beginning to rise up inside of me” or “my emotions are moving from intense toward the calmer zone.” Red, the highest zone of intensity, means “my emotions are heated up” and “my feelings are very big!” When you start to teach kids to use the thermometer you may find it helpful to laminate a thermometer like the one shown in Figure 8 and add a laminated arrow with Velcro so kids can place the arrow on the thermometer to represent the different levels of intensity of their emotions. You can help kids read books, guess what the characters are feeling by pointing to the feelings chart, and then go to the sensory chart and have kids point to the sensations and then identify whether they're small, medium, or large.

Karen Van Patten at the El Dorado County Office of Education made the example seen in Figure 9 for me. It was highlighted in our book as a way for children to choose things they can do as they are learning about feelings.

Figure 9. Identifying feelings in self.

It says, "I feel," and the child gets to move the feeling to underneath I feel, and in this case it's angry. The next part says, "I can," and then it gives them an idea of what they can do to regulate their emotions. This one says squeeze a ball. Once I'm calmed down, am I ready to return? Do I feel focused? Thumbs up. This is one way to help children learn words for different feelings, learn how to recognize their own feelings, and learn to recognize how small, medium, or large the feeling is using any of the following:

- Small, Medium, or Large

- 0-10 Scale

- Red, Orange, or Green

- Lion, Bear, Cat

Step 3

When My Sensations or Emotions Are in the Orange or Red Zone (Medium/Large) Then I Have to Pick a Self-Regulation Strategy to Manage and Calm My Big Emotions

In a perfect world, kids would be able to identify when they are in the orange zone. Once we get in the red zone it's hard to come back. We're often hurting ourselves, others, or property. Catching our zone in the orange and bringing us back to green sooner is a much better strategy. We have to get really good at that by practicing over and over and over. Then, I can pick a self-regulation strategy to calm those big emotions.

Here is an adult example of something that happened to me. I had been doing training after training and I didn't have any restorative time. I think my emotions were rising up into the red zone from expending all that energy in training. All I looked forward to was Saturday. I was going to spend Saturday with my husband and it was going to be a restorative time. I couldn't wait. Saturday morning came, I woke up, and it was like there was an emotionally dark stormy cloud around my head.

I was on edge. Let's think of the four clues or sensations in your body. I remember my neck was up to my ears and tense, like a knotted thing around my neck and my head and everything was tense. Thinking about my emotions, I was irritable and on edge about everything. Reflecting on my behavior, I was criticizing everything that my husband did. Why'd you put my laptop cord here? You don't love me, this is proof. These waffles you made are so soggy! Don't you know how to make waffles?”

It’s important that you know I've spent a lifetime practicing these skills. About 15 minutes into this I recognized oh no, I am in the red zone. I am so out of control right now. I'm really in that red zone and my thoughts were like he couldn't do anything right. Those were my four clues.

I said to my husband, "Oh my gosh, I am out of control right now. I need to go do something to take care of myself." I went on an eight-mile hike, I came back, and I took a 20-minute nap. Then I walked down the stairs to meet him for dinner and I said, "You are the most beautiful person I've ever seen." Now, did he change? No, my zone changed. The glasses I was wearing changed from red zone glasses to green zone. The more we teach kids this, the more they'll grow up to be adults to catch themselves much sooner when they're in that zone and being able to bring themselves back down before they do harm.

Just Breathe!

One of the ways we can help children regulate is through the breath. Let's look at this scientifically first. When you inhale, you stimulate the sympathetic nervous system, which makes your heart increase. It's called the accelerator. Take a deep breath in. When you do that, you're stimulating your sympathetic nervous system, which is like the accelerator of your body.

When you exhale, you stimulate the parasympathetic nervous system, which decreases, like the brakes, how fast your heart beats. The more anxious or nervous you get, the more in-breaths you take, which subsequently cause you more anxiety. The more out-breaths you take, the more you're slowing yourself down.

For example, if you're bored in a training and you yawn it's because you're taking an in-breath, naturally trying to wake yourself up and stimulate yourself. In calm individuals, the inhale and the exhale are working at a 50 mile an hour pace. You're in the zone and have a sense of well-being.

One of the things you can do to help calm and regulate yourself and to teach children how to use their breathing in a way to calm themselves. Breath is the remote control for self-regulation. But you have to learn how to use belly breaths rather than chest breathing. You can teach children to do this as well. To take a belly breath, lay flat on the floor and put a teddy bear, tissue box, or book on top of your belly. Pretend your belly is a balloon. When you take that deep breath in, the balloon should blow up. It's like you're breathing air in and blowing your balloon up. When you breathe out, the book, stuffed animal, or tissue box should go down. When you use breath like that, called diaphragmic breathing, you can help yourself and children calm the regulatory system.

Sesame Street has a series of social-emotional and trauma-informed videos. There's a wonderful video featuring Elmo, Common, and Colbie Caillat singing “Belly Breathe.” I'd like you to take a moment to go to SesameStreet.org, choose videos, then search Elmo for “Belly Breathe.” Watch the video then come back and join me.

After you watch the video, think for a moment about what you learned. Elmo was like me when I woke up upset that Saturday morning. Elmo turned into a monster, but after he did his belly breathing, he calmed back down and felt like himself again. This is a wonderful video to show children to help them regulate and calm themselves.

When children are calm, there are so many other ways that we can teach kids how to use their breath proactively. It's like an emergency responder first aid kit. What tools are we going to help children use to regulate themselves in the middle of an emotional emergency? Here are some other ideas to teach children to use their breath.

Feathers are a great visual for children. Have two children partner together. One has a feather and they have to blow it off their hand. They have to take a deep breath in then blow the feather. The other child has to catch it. They can try long exhales and short exhales.

Stuffed animals or breathing buddies is belly breathing like we just talked about. Have children lie down on their back and make the bear or the breathing buddy go up and down. Wouldn't it be great if you had a breathing buddy in your classroom setting or in your family child care home? Families could even have one at home. You tell them that this is Buddy the breathing bear. When you need to take a deep breath, you can go and Buddy will help you breathe and calm down. Another classroom got a huge sloth stuffed animal. Sloths are some of the slowest animals in the world. The kids would go sit with the sloth when they were all revved up emotionally to breathe with the sloth and calm down. These are creative visuals to help kids calm and breathe.

You can teach them how to do balloon breaths where they breathe in then out to blow the imaginary balloon up. You can also use a real balloon and show them how balloons expand and contract, just like your lungs. You can also teach them to pretend to smell the flower then blow out the candle. Practice those kinds of activities with children.

Regulation

If you're working with infants, most of the way we regulate infants is through us. We walk them, we rock them, we hold them, we read a book, we hum or sing, and we talk in a soothing voice. Infants don't often calm themselves. We calm them. They rely on us to be the co-regulator of their internal world.

A really important concept for you to remember with all children is that you are the external Wi-Fi to the internal world of a child. You know how when your cell phone says low charge and you panic and plug it into the wall and then it gets charged back up? That's what kids do with us all day. They become dysregulated and then they come to us to plug in to us. They use our calm, our sense of safety, and our presence to plug in and calm themselves down. We can begin to teach toddlers and preschoolers other strategies, such as playing with clay or sand, blowing bubbles, or taking belly breaths.

Resources

There are some wonderful resources that I want to recommend to you to help kids manage big emotions and self-regulation skills.

The first one is a book called Calm Down Time. It's for infants and toddlers, but mostly toddlers. It's a very short book that teaches them how they can calm their own bodies down. Every child needs a safe person, that's you, an object, maybe their teddy bear, or a place they can go to calm themselves down.

Breathe Like a Bear is a wonderful book because each page has a different story. For example, they have a soup story and you take the kids through a very simple activity. Hold your favorite bowl of hot soup in your hands. Okay, sniff your soup, what does it smell like? Okay, it's too hot to eat, so we have to blow on it to cool it down. There are different stories in the book like that.

I love the book Mind Bubbles because it teaches kids that emotions are small, medium, and large. But eventually, the bubbles pop, and emotions always go away. We just need to buy some time with a self-regulation strategy.

Other resources include Yoga Pretzels and Mindful Kids card decks. Those are separate decks you can purchase for kids age four to 104. Each card has either a mindfulness or a movement activity that helps kids focus on kindness, calming their bodies, and regulating their bodies.

These are wonderful tools and resources for children to promote self-regulation because when they actually have huge emotions, they have a higher likelihood of doing that new habit you've taught them and you can prevent challenging behaviors when you teach those steps.

Step 4

Think, Think and Think of a Solution to My Problem

When children become dysregulated, the number one goal is to calm their emotionally dysregulated brains and bodies through you, through a safe place, through safe objects, or safe activities, like blowing bubbles or breathing. Once they're downstairs emotionally reactive brain is calm, then you can finally help them think, think, think of a solution. When a child becomes dysregulated, they have a problem. They want something or they are trying to avoid something. They are trying to gain something or express an emotion. But they can find a way to solve their problem.

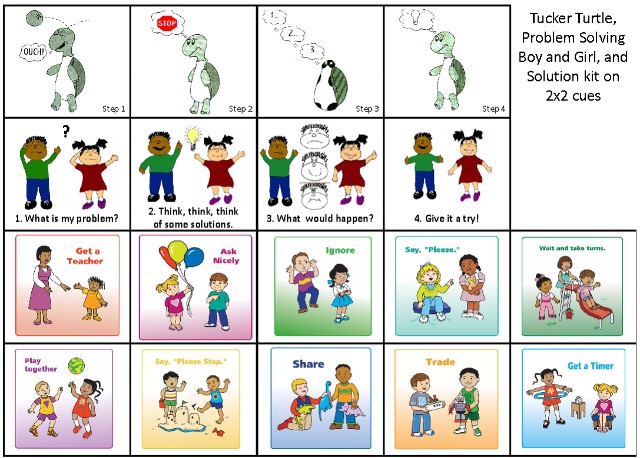

Figure 10 shows some templates you can print out at challengingbehaviors.org or www.cainclusion.org. The first row in Figure 10 shows Tucker the Turtle. These cards can be printed and laminated as a story with subsequent activities. Tucker the Turtle teaches children how you can tuck in your shell, count to three, take three deep breaths, and when you're calm, come out of your shell and think, think, think of a solution. There are also these wonderful solution kit cards you can print as small cards, medium cards, or large cards then laminate them for use with children.

Figure 10. Sample problem-solving cards for solution kit.

You can create your own magical solution kit in a briefcase, a box, or post it on the wall. Then when children get take their breaths, get calm, and are ready to solve their problem, they can go to the solution cards and explore with you a way they can solve their problem that doesn't hurt themselves, others, or property. Examples include get a teacher, ask nicely, ignore, say please, trade, share, tell them please stop, or play together. These cards are available in English, Chinese, and Spanish.

Resources

As I mentioned previously, www.cainclusion.org is where you can find Tucker the Turtle as well as its female version, Sonya the Snail. There are also printable feeling faces, solution kit cards, self-regulation activities, and other ideas all available for free. Those same things can be found in different versions on www.challengingbehavior.org. Additional materials can be found at http://csefel.vanderbilt.edu/.

Another resource available is my app, Trigger Stop: Sensory and Emotional Check-in for kids three to eight. There's another wonderful app called Stop, Breath, Think for adults or older children. It actually walks you through checking in where in your body you are feeling various sensations as well as doing a check-in of your feelings. It's a sensory and emotional check-in for older kids and adults. Then it gives you a self-regulating mindful activity or a meditation that you can use to calm your over-regulated brain.

If you want to learn more about trauma, you're welcome to check out my book, Trauma-Informed Practices for Early Childhood Educators or Zones of Regulation, which I also referred to earlier. It's a curriculum designed to foster self-regulation, emotional literacy, and emotional control.

Thank you so much for joining me today and for being a brain architect. I'm so honored that I could be a part of your journey for just a brief moment. I wish you the best of luck and on this note, what I ask you, is if you can walk away with one thing today it's what is the meaning of the child's behavior. Just hold that mantra in your mind. You, everything you do, makes a lot of difference in the life of a child.

References

Herner, T. (1998). Counterpoint. NASDE, p. 2.

Nicholson, J., Perez, L., & Kurtz, J. (2018). Trauma-informed practices for early childhood educators: Relationship-based approaches that support healing and build resilience in young children. United Kingdom: Routledge.

Kuypers, L. (2011). Zones of regulation: A curriculum designed to foster self-regulation and emotional control. California: Social Thinking Publishing.

Citation

Kurtz, J. (2019). Preventing challenging behaviors, in partnership with Region 9 Head Start Association. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23737. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education