Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Nurturing Beyond Bars presented by Quniana Futrell, EdS

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- List factors surrounding incarceration that affect the child.

- Describe how to have non-stressful conversations around the sensitive topic of incarceration.

- Describe the significance of their role in helping these children and families.

Introduction

I'm so excited to get to present to you all on such an important, yet sensitive topic that I know many of you have faced. I am going to give you some pointers so you can continue in a more skilled way as it relates to children who have parents who are incarcerated. You get into it because you want to serve the community. A part of your community is this incarcerated population. Today, you will learn even more about how to serve them in a more efficient way.

Beyond my accolades, I am the child of two parents who were incarcerated as I was growing up, and I am currently the child of a mother who is incarcerated. I say that anytime I talk about this topic because I know I need to earn your right to be heard on a topic like this. I understand the significance of not only listening to someone who has read an article or read a book about it, but also the empathy side. I am speaking as the empathetic expert because I live this every day, and it is who I am.

Defining Resilience

We are going to start with one of my favorite words, resilience. The one thing that we remember about a rubber band is its elasticity and how it stretches back as far as you can make it go, but it still goes back to the original form. As it relates to this topic, what is resilience? Resilience is the ability of matter to spring back quickly into shape after being bent, stretched, or deformed. It is the ability to recover quickly from setbacks. I need you to understand that these children and their families are resilient. These children that you will face day in and day out that do have this particular trauma are resilient. Even though it is something that could potentially be deforming, whether it be their behavior or health, they still have the ability to bounce back. This is where we come in and give them the resources and tools to help them spring forth into becoming what they were created to be in the first place. We help them get back to who they were. That is what resilience is, and that is the role that you will play in helping these children see how resilient they are.

Let’s Talk Stereotypes

When it comes to this topic, these children have been stereotyped. You name it, they have been called it. What is the first thing that comes to mind after hearing a child say their parent is in jail? If you have ever encountered their parent before, the first thing that I have heard before is, "Well, I could tell this was something that was going to happen. They look like they got a parent that's in jail. Oh, goodness, I wonder if they'll go in there too." Oftentimes, these stereotypes misguide us in our judgment in how we are able to help these children and automatically assume based on our previous bias what the outcome of this kid will be. We may even stereotype this child by thinking, "The child will get over it. It's just jail, they'll be alright.” We may use that resilience to say, "They'll just bounce back from it." I beg to differ and you will see why.

There are nearly three million children that have a parent in jail or in prison. The stereotype is that they will end up incarcerated as well. Sometimes that is what people say, and kids may assume that what those people say is what will happen to them. Can we group all children dealing with incarceration together? Can we just look at a child and say, “This is what a child looks like who has a parent incarcerated"? “They just look like they don't have it together. They look broken, traumatized.” I definitely say, “No, absolutely not. There is no way to group them together.” Can this silent issue be resolved the same? How or why not? We have all these stereotypes and different things that we may think about these children. How do we move past that and stop generalizing all of them together in one box?

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)

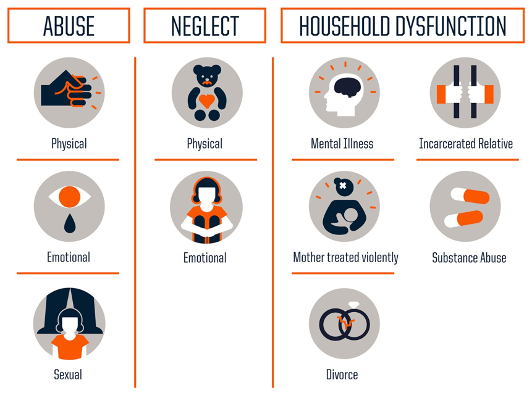

Figure 1. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs).

We are going to talk about how to help you get through stereotyping. I want to start with adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). Figure 1 from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation is a visual example of ACEs. Looking at Figure 1, when we think about abuse, this is an adverse childhood experience. Under that category of abuse, we have physical abuse, emotional abuse, and sexual abuse. Under the next topic, we have neglect, which can be physical and/or emotional. We also have household dysfunctions, including mental illness, an incarcerated relative, mother treated violently, substance abuse, and divorce. These are the three major components of ACE’s. There is more: how many layers are within mental illness? There is so much embedded in each of these that we have to take the time to understand them, especially as it relates to the children you are serving. I have learned that if a child endures two or more ACEs, they have to have some type of support. They have to have some type of resource or reference point to help them be successful in life.

Effects of Incarceration on Children

Moving forward, we are going to be geared toward having an incarcerated relative. Here is a fact from a study conducted by the California Irvine University:

- "The study found significant health problems, including behavior issues, in children of incarcerated parents and also that, for some types of health outcomes, parental incarceration can be more detrimental to a child's well-being than divorce or death of a parent."

Take a second and really analyze this. Parental incarceration can be more detrimental to a child's well-being than divorce or death of a parent. How could that be? When you take a look at stereotypes about those who are incarcerated, they are still alive. The children are still able, in a sense, to see them, talk to them, and write them, so how could that be? I challenge you to think about this: when a child experiences divorce with their parents, there is typically a conversation that occurs. Whatever the family dynamic may be, they sit down with the child and say, "We've determined that it's more healthy for our family if we live in two separate households.” When moments like this are shared with those who are in the closest circle with this child, being a teacher or social worker, they usually respond with, "Okay, how can we help?"

Let's look at the death of a parent. This is probably the hardest conversation to have with a child. There is therapy that will be mentioned and there is so much remorse and sympathy that will go out for this child. But the moment you say, "Their parent is incarcerated,” sometimes we do not know what to say because this topic is so taboo and sensitive. With divorce or the death of a parent, it is a bit more of a welcoming conversation. What we have to do is start making incarceration a little bit more welcoming as well. Making incarceration not the word that makes you uncomfortable, but one to help you understand. Your ultimate goal is being a resource to the families, so responding in a proper way is helpful and supportive.

Factors that Affect the Child

Here are the factors that can affect the child:

- At what age the arrest occurred

- The child’s presence at the arrest

- The stability of the family prior to the arrest, conviction, and sentence

- The disruptiveness of the incarceration

- The strength of the present child-parent relationship

- The influence of siblings

- 1 in 14

Whether the arrest happened at age five or 15, it is going to matter. This is because the development of that child is different depending on ages and stages, so it is going to affect them differently.

The child's presence at the arrest alone means so much for so many different factors. First, if they were present during that arrest, it is going to likely affect them more than the child who was not and has to deal with the aftermath of being told. Research has told us that children who were present during the arrest experience bedwetting nightmares because this is something that gets replayed in their minds. This is a traumatic experience that these children are now witnessing firsthand. Being in the social work field there are so many different traumatic cases I am sure you all face, and when these children are witnessing something as traumatic as this, it certainly impacts them mentally, socially, emotionally, and sometimes physically.

How stable was the family prior to the arrest, conviction, and sentence? Were they already struggling? Were they doing well? Were both parents in the household? All of this affects the child. When we think about the stereotype of grouping them together, there are reasons as to why we cannot because some families were not stable beforehand. We may think, “They were not used to Mom or Dad being around anyway.” But depending on the stability it is going to affect the child differently based on prior family stability of the arrest, the conviction, and the sentence of the parent that is going away.

With the disruptiveness of the incarceration, let us consider recidivism. For example, a parent comes home after a year and it is Christmastime. They do not have the money for Christmas and they feel pressure, can't get a job and may re-offend. The children have Christmas but the parent is not there because they thought that was more important. Now she is away again after being home for a few weeks or months. That back and forth is going to affect the child greater than a parent doing 10 straight years. If a parent goes away and does 10 straight years, the child gets used to that and is able to deal with that a little better.

The strength of the present child-parent relationship is important as well. Going back to the stability of the family, if the child did not already have a strong relationship with the parent who goes away, it may not affect the child as much. Will it still affect them? Absolutely, just depending on the strength of the present relationship.

The influence of siblings is a big one because if the child is the oldest of five and now a parent is gone, they have to step up with help that is going to be needed around the house. Now you have to play a role in getting them out of bed, cooking, and washing clothes. There are going to be so many other things that now affect you differently based on whether you have siblings or not.

I also wanted to throw in a fact. There are one in 14 children in the United States that have a parent incarcerated according to USA Today’s study in October of 2015. I will also tell you that prior to that study it was one in 28. The numbers doubled, if anything. For every 14 children that you encounter, one of them will have a parent incarcerated. Additionally, from one in 14, one in nine are African American children and one in eight are children who are poor. The effects of race and socioeconomic status matter and go into effect on how parental incarceration will impact a child's life.

Family Stressors

We know how it is going to affect the child, but let’s look at the family because in your line of work you are dealing with both. Your ultimate goal is to serve them and get them back to being healthy, so there are some stressors that you need to be aware of. This includes the family being restructured. For example, if the father, the primary breadwinner, goes away and the mother was a stay-at-home mom for the last 10 years, she may not have had the opportunity to pick up skills. Now, guess what? This family’s world is now undone because she has to figure it out and step up to go into the unknown world of how to care for the family financially. With the financial stress of having a parent away, that is a loss of income. Now, something has to be done to move this family forward in a way that keeps them from falling apart.

We also have the unknown factors and we could be here until next year going over those, but I will give you a few. There are the expensive phone calls and the commissary because the family member who is away would like some type of luxury. That puts stress on the family who is at home to pick up another bill. There is also visiting the family in prison. If you have never visited one personally or with a client, it is never a prison just around the corner from your house. The drive is at least 30 to 45 minutes. There is the clothing the incarcerated family member has to wear, and the things they may want from the vending machines. The children have to experience being searched to make sure they are not trying to bring anything in. If you are bringing a baby, you have to change your child's diaper in front of an officer so they can be assured that you are not trying to bring anything in. That whole experience alone is stressful for many families when they are dealing with this.

The Role of Social Workers

Now, what role do you play in this? What do you do? You allow your passion to kick in because I understand the overload that many of you face and the thought of adding anything to that gives you a little anxiety. But I want you to breathe and know that this is just going to help give you skills so that when you are in this, you know just how to recover through it quickly and be a little bit more efficient with these children and their families.

Define Your “Why”

Think for a second; why did you go to school? What was it that pierced your heart and said, “This is the line of work for me”? You chose social work and there is a reason behind that so that passion has to be the thing that drives you every single day, especially when you do get those cases that involve incarcerated family. Defining your “why” is one of those tools I love to give because no matter what you are faced with when you are reminded of your why you will get through it. Even in this, learning something new and tackling something a little differently, that is all going to come through by defining your “why.” Pause this for just a second and define your why. Truly write it out.

When I was a professor teaching early childhood, I would ask my students why they wanted to work with children. I am going to give you the same disclaimer I gave them: you cannot say, “Because I just love helping people.” Your reasoning has to go beyond your love of it because if simply loving to help people is your reason, that is not going to be enough to keep you. You have to dig a little deeper. For these families they may not be acting professional when you still have to remain so, you need to still want to help people. Sometimes people will not want your help and can anger you to a place where you are ready to pack your stuff up and say, "I don't even think this is for me anymore.” Know and define your why, especially if you are going to truly help these children and their families that are affected by incarceration because all scenarios are going to be different. You will have some that will love your help and some that are going to look at you side-eyed trying to figure out why you are helping them. Remember to enjoy your career. You have the best job in the world, the gift of social work, and truly understanding that it is a gift. It is an honor to serve people. I applaud you for deciding to do this work because not everyone can do this. The fact that you are, just goes to show how important you truly are to impacting this world for the better.

Professional Explanation

How do we explain this professionally? If a child was to tell you that their parent is now incarcerated, what do you say to them? Is it your role to become the therapist and social worker? Professionals and family members who have the responsibility of explaining incarceration to a child often give answers that are not true. So often, children are told a lie before they are ever told the truth about where their parents are and that is not okay. Telling them that lie pushes them into bad habits or people or things when those things seem to be the ones they can trust more than you if they find out you lied to them. People have said, “They're just at school right now," instead of telling them they are in jail or prison. “They're at work.” I do classes for parents in jails and I have created a curriculum for them called Parents Behind Bars. I asked one of the mothers what she told her child and said she told her daughter she was in the hospital. We have heard of family members who said they are on vacation and others say they are in the military. These are some of the lies that are being told to these children.

Some honest ways that a professional can help when you have the responsibility is to say, "Mom and Dad had a consequence, and they have to live somewhere else right now," period. What I want you to understand with children and their development is that they understand consequences. For example, sitting at the dinner table, Sarah has peas on her plate and is not eating them, but wants a Klondike bar. But does she get the Klondike bar if she does not eat the peas? Absolutely not, so from a young age, children understand consequences. Helping them see that their mom or dad cannot currently live with them right now because of a consequence for a choice they made is a way to explain it.

It is important to remind the child that their mom or dad loves them and will miss them while they are gone. These children need to understand that they are loved because for many of these children they do not think they are. They feel forgotten, left behind, and even more so, feel like it is their fault. They may think, "Maybe if I wouldn't have asked for so much they wouldn't have had to go do some of the things they did. Maybe if I was a better-behaved child then maybe they would not have gone out and gotten into trouble." Whatever that trouble could be, that is the thought process of that child, but we know different.

Role-Play Scenarios

Scenario 1

Let's role-play a little bit here. For our first scenario, you and a preschool-aged child are in a conversation. The child is telling you, "Guess what? Last night, I went to go see my daddy in jail." This is not something that was already in your case. What is your next response to that child? Take a second and think. What do you say to that? In this particular instance, your only reply to that is this: "Wow, you had to go see Daddy in jail last night? How was that? Wow, that's awesome." If they say it was good, you hype it up so much. "Oh my gosh, wow, that's great.” If it made them upset, say, “I can understand that, but he'll be home with you soon enough. "Would you like to draw a picture or anything about it? Would you like to write a letter?" That is certainly your role and where you end it because anything outside of that will be getting into the therapeutic stage. It is important to talk to them about it, see how they feel about it, and move on while not letting it be something that you dismiss. What typically happens in a case like this is a child says that and the professional says, "Oh, wow, really, okay, moving on," and that is not what we want to do because it makes a child feel like their emotions are not validated and it is not important. We want to make sure these children know that you care and are here to try to help in any way that you can.

Scenario 2

Here is another scenario. You have a case with a child who visited her dad in “college,” and they say to you, "Last night, I went to see my daddy at college and everybody had orange jumpsuits." First, here is the thing that I want you to clearly get. It is not your role or your responsibility to tell this child where they really were. So what is your role? Take a second and pause. Your role in this is to hear the child out and leave it alone and that is it. There is not a whole lot to do in this case. You cannot say, "Oh no, sweetheart, that's not college, your dad is in jail. But he'll be okay, he loves you” and then try to go through everything to make them feel better. This does not work because the lie has been told to this child by people they trust and for you to be the one to undo it is a critical thing.

If there is no family, foster parent, or caregiver to help, then it is your social responsibility to try to soften the blow and that is where resources come in. Sesame Street has amazing resources, such as online videos and free tools that you can use to help with this conversation. That is how you can address it if that becomes your responsibility. If it is not, then your role is to just simply say, "Oh my gosh, you went to college last night to see your dad. That must have been awesome, but what kind of orange were they wearing? Was it the bright orange or was it like the salmon-orange color of my car, which one? Oh, I love that orange, that is so cool.” Then transition into whatever you were going to be talking about anyway. The thing is to not shatter what they currently know, that is not what this is about.

Here is the second piece of what we have to get into. If the child is in a situation where they have some type of caregiver, then it is your responsibility to let that caregiver know that the conversation took place. You can say, “I just want you to know that I'm not sure about what's happening but I want you to know that I am a resource here and available to you.” In this scenario, one of two things could happen. You could have a caregiver that tells you they are grateful and relieved, or you could have the other side. You could have the other case where the caregiver may say something like, “They told you what? Oh, no, I don't know what they're talking about." If that happens, you say, "Oh, that's no problem at all. I could have definitely misunderstood what we were talking about. Anyway, whether you need me just know I have tons of resources on different family dynamics, and should you need anything, I'm always here." That is how you end it there because there will occasionally be some that, no matter what you say, keep things in the house a secret and will not accept your help. Sometimes you could pay them and they would not even accept your help, because some people are just that strong on their family and keep things close-knit. Just keep that in mind, and do not take it as a gut punch. Do not do that, but certainly understand that there are different family dynamics and that is okay. It is okay for the ones that want your help and it is okay for the ones that do not. You can only be as effective as people allow you to be. Remember that in helping and serving your community in the role that you play, sometimes we have to understand that you cannot help and save everybody. That is the law of social work because if you could help everyone, a lot of these cases would be different. Understanding that in this scenario can truly help you out a lot.

A Word of Encouragement

As we are wrapping up, I always transition out in the same manner by giving some word of encouragement because I understand the heart of a person that gets into a field such as this. I understand how valuable your time is, and I do not take it lightly that you commit it to continuing your education and working to become a better professional serving these families. How could I not encourage you?

Here is a quote:

- "Nothing is impossible, the word itself says, I'm possible." By Victor Aguirre

Nothing is impossible and that includes this field. Although you were given a lot of information in this time that we have shared, it is not impossible because in your field of work, you are born to do it. Go back to your “why” to keep you motivated and use it as fuel to get the work done. Believe me, you will make it happen.

References

Citation

Futrell, Q. (2020). Nurturing beyond bars. continued.com/social-work, Article 28. Available from www.continued.com/social-work