..

Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Avoiding Professional Potholes: Everyday Ethical Social Work Practice, presented by Michelle Gricus, DSW, MSW, LICSW, LCSW-C.

Learning Outcomes

- After this course, participants will be able to demonstrate knowledge of the types of ethical dilemmas experienced by social workers.

- After this course participants will be able to determine personal and professional factors that may impact ethical choices.

- After this course participants will be able to recognize the role of diversity and social justice in navigating dilemmas.

Introduction

We are going to be talking about avoiding professional potholes and areas that you may be unclear about.

Warm-Up Quiz

Let's get started with a warm-up quiz. You do not need any pen and paper for this.

Here are the questions:

- How many years ago did you get your driver's license?

- How many times in the past have you sought out formal instruction to improve your driving skills?

- Do you consider yourself a good, safe driver? More importantly, do others?

- Besides CEUs, what do you remember about the last ethics training you took?

- When was the last time you read the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) Code of Ethics?

- How familiar are you with your agency’s policies and procedures, especially those that protect you and the people with whom you work with (e.g. clients, patients, etc.)?

- Do you consider yourself a good, ethical social worker? More importantly, do others?

This quiz is a tune-up for those areas that we might not be as confident in, no matter how long you have been in the practice. Taking a look at those areas will improve our practice and make us better social workers. Regarding the last ethics training, you took, what stood out to you? Was it something that allowed you to think more critically about an ethical dilemma you found yourself in?

This training is not intended to have you memorize the Code of Ethics. It is not my responsibility to go over every aspect of the Code of Ethics. As a licensed social worker, it is your responsibility to know and understand the various components of the code and how they impact your particular practice.

When you think about clients and patients, are you aware of the policies and procedures in your agency? You need to be aware of those policies because they protect you and your patients, as well as protect you from them. They also protect you from the negative consequences of not following those policies and procedures and when those policies conflict with one another.

During this course, I hope that you will reflect on your own practice. Good ethics training will help you walk away with ideas that you had not thought of in a while, or will help you with your next ethical dilemma.

Code of Ethics

It is not my intention to go over every aspect of the NASW Code of Ethics. I do hope that you know how to access this document and that you are familiar with everything we are going to be talking about related to that. I wanted to remind you of the six ethical principles that are connected to the six values of social work.

The first ethical principle is how social workers' primary goal is to help people in need and address social problems. This is connected to the social work value of service. Our goal is to elevate service to others above self-interest and to draw on your knowledge, values, and skills. This helps people in need to address social problems. Did you also know that this value encourages you to volunteer a portion of your professional skills at no cost?

The second one is that social workers challenge social injustice. The idea is that you will pursue social change with and on behalf of vulnerable, oppressed individuals. Your goal is to promote sensitivity and knowledge about oppression, as well as cultural and ethnic diversity. Strive to ensure access to needed information, resources, equality of opportunity, and meaningful participation in decision-making for all people.

The third principle is that social workers respect the inherent dignity and worth of the person. We can often relate to and think of this principle when someone asks about the values of social work. This connects to the dignity and worth of the person, which indicates that we treat each person in a caring and respectful fashion. While being mindful of differences, we promote clients' socially responsible self-determination. We seek to enhance clients' capabilities and opportunities to change and address their own needs. We should be cognizant of the dual responsibility to clients and society. Regarding this, we look to resolve conflicts between clients' interests and the broader society's interests in a socially responsible manner.

The fourth principle is that social workers recognize the central importance of human relationships tied to their value. In this case, social workers understand that relationships between and among people are an important vehicle for change. Social workers engage people as partners in the helping process.

The fifth value is that social workers should behave in a trustworthy manner. Remember to have integrity and be aware of the professional standards. We need to act honestly and responsibly, as well as promote ethical practice at the organization or agency where you work.

The sixth principle is that social workers practice within their areas of competence and develop and enhance their professional expertise. This is related to the value of competence. You should be striving to increase your professional knowledge and apply that to the practice. Social workers should aspire to contribute to the knowledge base of the profession in any number of ways. This could be through formalities such as research or supervision. Informalities include bringing up standards and codes as you deal with ethical dilemmas in your practice and talking with clients and colleagues.

Social Workers’ Ethical Responsibilities

You have a number of responsibilities as social workers. The numbers next to each stakeholder indicate how many principles or standards are related in each area:

- To clients (17)

- To colleagues (10)

- In practice settings (10)

- As professionals (8)

- To the social work profession (2)

- To the broader society (4)

We have the most responsibility to our clients. However, that does not mean that it takes precedence over all other areas. It does mean that there are nuances to the client work that we may not always have a clear picture of. The 17 client standards help us identify those nuances and complicating factors. The idea is to familiarize yourself with these different standards and have a clear understanding of your expectations as a social worker, as opposed to another type of licensed professional.

Do you know your responsibilities?

I have another quiz testing your responsibilities.

These are the true or false questions:

- The 2017 revisions of the Code of Ethics (COE) focus on technology and electronic communication standards.

- Social workers are not prohibited from engaging in sexual relationships with former clients as long as it has been at least 5 years.

- If a social worker becomes aware of an impaired colleague, you should consult with that colleague first before going to a supervisor.

- Social workers have a duty to engage in social and political action.

I would like you to pause and answer the questions if you need time. Write down what justifies your response.

In this case, the first answer is true. When the 1996 Code of Ethics was released, the Internet was not yet a component of everyday social work practice, so the 2017 revisions include those changes.

Number two is false. According to Standard 1.09, there is no acceptable limit. Social workers should not engage in sexual activities or contact with former patients, regardless of the timeframe. This is because of the potential harm to the client. If the social worker engages in contact contrary to this prohibition, in that there is an exception that should be warranted, that is the only time when a sexual relationship could happen. It is not something that is explicitly identified with a time limit.

The third answer is true and is related to Standard 2.08. Social workers who have direct knowledge of a colleague's impairment due to personal problems, distress, substance abuse, or mental health difficulties, should consult with that colleague first and assist that person in taking action. If the colleague has not taken adequate steps to address their impairment, then you go through the agencies or employers.

The last answer is true because you have a duty to engage in social and political action, according to Standard 6.04. It is our responsibility to ensure that all people have equal access to resources, employment services, and opportunities in order to meet their basic needs.

If you were not able to identify these answers correctly, I encourage you to review the Code of Ethics at the end of this training. It is not important that you memorize every area, but it is important that you understand what your responsibilities are as a licensed social worker. This is especially true if you find yourself licensed under a number of different codes related to your employer that may go against what the Code of Ethics for social workers indicates.

Ethical Dilemmas in Social Work

Here is what we will cover in this section:

- Common social work “potholes”

- Common ethical dilemmas

- Ethical decision-making framework

An Autobiography in Five Short Chapters (1977)

I want to talk about a story by Portia Nelson called "An Autobiography in Five Short Chapters.” As I read this, I would like you to think about the ways in which this applies to your own personal practice. It is possible that you knew about this story, but have not thought about it in terms of your professional practice.

Chapter One says, "I walk down the street, there is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I fall in, I am lost, I am helpless, it isn't my fault, it takes forever to find a way out." Chapter Two says, "I walked on the same street. There's a deep hole in the sidewalk. I still don't see it. I fall in again. I can't believe I'm in the same place. It isn't my fault. It still takes a long time to get out." Chapter Three says, "I walked down the same street, there is a deep hole in the sidewalk. I see it there, I still fall in, it's habit, it's my fault. I know where I am, I get out immediately." Chapter Four says, "I walked down the same street, there was a deep hole in the sidewalk, I walk around it." Chapter Five says, "I walked down a different street."

You can jot down your thoughts or stop to think for a few moments. I will proceed, but feel free to pause at any moment and think about how these things can relate to your own practice.

Social Work Potholes

Social work potholes are places where we have a misstep. Maybe part of our practice has become obvious to us, but only because we have been getting tripped up. Just like with driving, we can slip into poor practice. You may be an excellent driver because you have not gotten any tickets or been in any accidents. However, have you had close calls? Maybe you saw a police officer, but prior to that you were driving distracted. It is important that we think about our social work practice in the same way. We can slip into poor practice if we are not being mindful. We can tighten up our practice, which is why completing ethics training every few years has become a national requirement. No matter what licensing board you are a part of, you are likely taking this course because you have a number of ethics training hours that you need to get with every licensure renewal.

What are some of those areas for you that show up as poor practice? One aspect that can be complicated about social work practice, particularly ethics training, is that we are not in agreement about what to do with complex issues. For example, you may talk with a colleague about a boundary issue that comes up. It could be something as simple as receiving a gift from someone you are terminating services with. Some people may freely accept that gift and others may turn down the gift. We are not always in agreement with complex ethical issues and that is important to consider.

That leads us into why the Code of Ethics does not tell us explicitly what to do in every situation. While that may feel reassuring, it can also be frustrating to think of the Code of Ethics as a rulebook or to-do list. Instead, it is there to give us a wide scope of ideas, suggestions, or concepts. It is not something that allows us to resolve problems because there may be two standards going against each other. It may not always be evident which course of action should be taken.

Another pothole is that your boundaries may not be the same as my boundaries, even if we have the same job and work with the same individuals. You may find that in one case you say agree to something and a colleague does not. The client with whom you are working with may be confused by that and ask, "Why did you agree but the other person did not?" What complications can that create in a professional relationship?

Another pothole is about how breaking rules may be necessary in this line of work. It is not required that you agree to everything I am suggesting. However, I am hoping that you will think about this from a standpoint of confidentiality, sharing information in the way that we document, and the ideas around that. We are sometimes breaking the law in order to protect our own ethics or values.

These potholes can show up in a number of ways across different professional spectrums and settings. All of this should help us to see that being an ethical practitioner takes time because it takes reflection and diligence. We want to make sure that we are not practicing the same way throughout our entire professional careers. Just because you have 20 or 30 years of experience does not mean that you are not falling into these potholes from time to time. Where in your schedule can you take time to be mindful? It may be clear to you that carving out time is important, but others might say, "That is why it is imperative that I make ethical decisions quickly so I can move on."

What is an ethical dilemma?

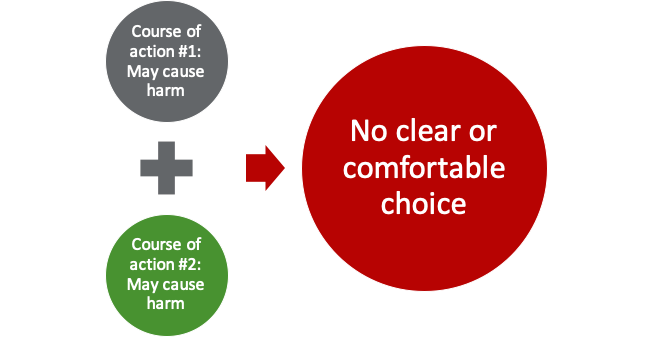

An ethical dilemma is when we are faced with two issues where there is a conflict. No matter what we decide, some harm will be caused.

In this case, I have oversimplified it here in Figure 1:

[Figure 1]

If both choices can cause harm, we are in a predicament where there is no clear choice. True ethical dilemmas cause us to feel conflicted, leaving us to wonder if we made the right choice. I encourage you to reflect on the ethical dilemmas that you ran into when you were first starting out, as well as the ones that are more recent. Are they more complex now? Are there other factors that can get in the way? Are there more clear guidelines in some areas and less so in others? Each one of us is going to struggle with these dilemmas in different ways because of how we are made up, what our histories have been, and what we value.

Types of Professional Ethical Dilemmas

Here are different types of professional dilemmas:

- Applying rule: unclear rules/laws

- Conflicting demands: laws/policies/what people want

- Needs of others: taking responsibility for others Transgression: what to do about a wrongdoing

- Social pressure: identity-inconsistent

- Internal conflict: personal and professional values clash

Some of the ethical dilemmas we can run into look at unclear rules. Maybe there are some things that conflict and we are not sure what path to follow. These could be related to rules or laws that you deal with on a regular basis. They may only become unclear when faced with a different circumstance concerning a particular type of individual who may have a characteristic that makes the situation more challenging.

Another professional dilemma is a conflicting demand. What people want may conflict with the laws or policies of your organization. Another type of dilemma could involve the needs of others. How are we taking responsibility for someone else in a way that aligns with our professional responsibilities, but also allows for self-determination? Where is that line? When should we allow people to make decisions for themselves, and when is it appropriate for them to ask us for help?

Transgression is another type of ethical dilemma in which we try to figure out what to do about wrongdoings. For example, you know that someone you work with who is breaking the law. Do you report that? In some cases, you would say, "Yes, absolutely." Other times you might say, "No, I would not."

Social pressure is another type of ethical dilemma, where the challenge is identity inconsistency. It could be that everybody on your team is doing something a certain way until you feel pressured to go along with that, even though there is something in your gut that tells you not to. There may be pressure because of time or budgets. It may not be related to an individual, but rather from other places that can come from other people that cause us to have some conflict within ourselves.

That leads us into the last type of professional ethical dilemma, which is an internal conflict. Focus on how this can be happening as a struggle within ourselves when our personal and professional values clash. The first three types of ethical dilemmas listed here are the top identified issues by social workers. You might find that it is another area that you experience the most conflict. Either way, it is important to note that not all ethical dilemmas are the same and they do not all fit in the same category.

Common Scenario 1

I want to provide common scenarios for you as a way to think about ideas, not necessarily to capture every nuance of the case. Hopefully you will be able to connect with a scenario and relate it back to the Code of Ethics.

This scenario is about you working with a client who actively uses illegal substances. Do you report that? This may be clear to those who work in a corrections facility or treatment center that has a zero-tolerance policy. It may be a gray area for others. You might say, "I feel that I should report that because it puts the person at risk," but others might say, "No, I would not want somebody involved in my business that way," as well other responses in between.

Take a moment and think about the social work values that would apply in this situation. What are the components of your social work practice that are the most important to dig into? According to the Code of Ethics, the values that are at play here are the dignity and worth of the person. This is because the social worker seeks to resolve conflicts between the client's interests and the society's interests in socially responsible ways. The way we deal with it should be consistent with values, principles, and the ethical standards of the profession.

Another aspect to consider is the importance of human relationships. There needs to be trust between the client and the social worker. If you report somebody's illegal activities, it is in direct conflict with those ideas. Another way to think about this is through the value of integrity. We have to practice in a way that is honest and responsible. We are connected to the laws and policies of the agencies and communities that we serve.

Lastly, we want to think about our responsibility to social justice. The law can seem unfair sometimes, or the client's situation may feel precarious, and it is important that we think about how discrimination has played a role in this person's life. What injustices might this person encounter if we report this individual?

What we can see in the situation is that there is no clear answer. If we report, we may be violating our own values and the trust within the relationship. If we choose to not report, we may be violating our sense of what is important in society. One of the biggest challenges of dealing with ethical dilemmas is that we have to make a decision at a certain point. The fact that we face these issues on a regular basis can cause a lot of stress in our work as social workers. It is important that we look at the complexities of each value.

Common Scenario 2

In this case, a former client locates you on social media and requests to stay in touch. Do you accept the request? Think about those six values and see what applies in this case. We have conflicts relating to the dignity and worth of the person. You want to respect your client's right to self-determination. It is not the client's fault that they can find you on social media. However, as social workers we can make a person feel terrible about instances like this. We may say, “You should never have done that. It is inappropriate that you contacted me.” The client will not understand that it is a boundary issue. It is our responsibility as the social worker to be clear about what those roles are.

One area to consider is the importance of human relationships. We know that social media is everywhere and may be the only way some people choose to communicate. A client may feel rejected or slighted if you do not accept the request. If you leave it in limbo, what does that communicate to the individual? You do not have to accept the request, but you do have to take action. This means either accepting the request, responding to the person about why you are not going to accept the request, or denying the request. Again, the complexity is that we are thinking about relationships and how conflicts can show up in confusing ways.

Another area has to do with integrity. We have to act in a way that is consistent with agency policies, even if it could get in the way of a relationship with a client. For example, your agency may have a clear policy on social media with regard to current or former clients. On the other hand, they may have an ambiguous policy and you will have to personally decide what to do. What is your personal comfort with having your professional and personal identities overlap?

The last of the values in this particular scenario is competence. You have to be a competent user of technology. You may say to yourself, "How did this person find me? I thought I did a good job of hiding myself,” or, “It was not clear to me that other people could locate me." That is our responsibility as a person existing in this world. With the revision of the 2017 Code of Ethics, we now know electronic communication is an area that we need to develop competence in, as well as be familiar with the various platforms and the ways in which we have a digital footprint. You may want to think about these areas as they relate to this scenario. This is specific to electronic communication, but it can apply to other boundary issues as well.

Ethical Decision- Making Frameworks

There are many frameworks in social work that can help us make a decision. They can be rooted in a series of questions, flowcharts, or acronyms. These frameworks have the same process.

The first step is to define the problem. You need to recognize the issue and get the facts. What happens is that an ethical dilemma for you may not be an ethical dilemma for someone else. Recognize what those conflicts are, as well as the appropriate courses of action.

The second step is to identify the costs and the benefits of all parties, including yourself. Ethical dilemmas can be about figuring out a client's circumstance that is causing harm, and we often do not think about the impact it can have on us. It is important that we think about the agency as well. We might be thinking about larger societal issues, especially if a person is engaging in a negative action. We may say to ourselves, "If I do not report, this person could put other folks in harm's way." Again, it is important to look at all parties. Be realistic about costs and benefits as well. Sometimes, especially when we want to head into a certain direction with our ethical dilemma, we do not identify all the costs and benefits. We may only identify the benefits of the choice we want to make and the costs of the choice we do not want to make. Be careful to do both sides of each stakeholder.

The third step is to consult with another person whenever possible. You can get support by using the Code of Ethics or going to others that may have faced a similar situation. If you are not able to access another person, you can reference literature about various types of ethical dilemmas. An important part of tackling an ethical dilemma slowing things down. Many of you might be saying, “I do not have time. I have to make a decision." For example, if somebody has given you a gift, you cannot say, "Before I accept that gift, I need to go back and refer to the Code of Ethics and talk to my supervisor.” In the moment you may feel like you do not have a lot of options or enough time. However, it is important to weigh those options out with the person. In this case, saying that you are feeling conflicted can buy you time to think things through. You can also consult past situations that you have been in.

The fourth step is to evaluate all available options. What do you see as being those options? How might you implement them? You most likely will not feel confident in your options because in a true ethical dilemma, you have scenarios where harm is going to be caused. If you accept the gift, that may cause harm to you if you grow to feel guilty about it. The person may feel that you owe them something as a result of this. If you do not take the gift, that individual may feel rejected or think that you do not like them.

The fifth step is to implement your decision. This is when you can let your personality and style shine. There is no right way to do this. For example, you can let people down in a gentle way or accept things in a brutal way. There are other ways that we can go about doing this.

The final step is to review the outcomes of the decision we have made. How did that person respond when we accepted the gift or did not accept the gift? Do we wish that we could have done something differently? The idea is to walk through each step. In looking at both simple and complex dilemmas, it is easier and more helpful to have the process be the same each time.

Take a moment, reflect on any ethical dilemmas that you have experienced recently or are currently experiencing, and walk through these steps.

Factors that Influence Decision-Making

This next part is about attending to you and your vehicle. This is about who you are and what you bring to the practice.

This is what we will cover in this section:

- Psychological challenges that can influence decision-making abilities.

- Personal circumstances that can interfere with ethical decision making.

- Compassion fatigue

Remember that it is important to connect with reflection and your own self-perceptions because it can be useful in navigating ethical dilemmas.

Scenario

You recently made a mistake at work that had significant consequences for a client. For example, you missed a court filing deadline or forgot to send in the check to cover a client's emergency rent. You feel badly about the decision you made, and your boss responds by saying, "This is not the first time you have made a mistake that has caused harm. You are on probation.”

Under Pressure

Here are some distinctions within pressure:

- Self-Focus

- Pressure increases anxiety and self- consciousness about performing correctly, which gets in the way of our automatic thinking

- Distraction

- Pressure fills working memory with thoughts about the situation and its importance.

○ These thoughts compete with the attention you would normally have available for tasks.

In this case, you were already feeling bad and now that you are on probation, you feel like you are being watched. Some challenges that we can experience under pressure is that we start to focus on ourselves. You may start to relate this to other times that you have felt pressure in your life, such as personally or financially. As pressure increases, our anxiety and self-consciousness about our ability to perform correctly increases as well. Those factors can impact our thinking processes that we take for granted on a regular day. Instead, we are focusing on the fact that we made a mistake, and makes us more susceptible to making another. It is competing with our attention, so we are not able to focus and get distracted thinking about the mistakes that we made. It is like rolling tumbleweed that is gathering momentum. If you feel pressured by specific areas that you do not want to mess up in, it makes you even more pressured to not make a wrong decision. This psychological ramification can have longer-lasting effects.

Cognitive Dissonance

Cognitive dissonance is when we feel a certain way about ourselves but then do something that opposes that belief. We may not be able to identify it in the moment, but it still makes us feel anxious, guilty and shameful. We may want to react by hiding, rationalizing our choices, avoiding evidence that we were in the wrong, and refraining from being in situations that make us feel worse. If you have experienced this, especially when dealing with a professional challenge, that is cognitive dissonance. We often try to justify the situation by saying, "I deserved this," or, "That person took it the wrong way."

Personal Examples

Let's take a look at a couple of examples using some images. Figure 2 is an image of donuts:

[Figure 2]

Yesterday may have been a hard day at work and you want to start today on a high note. You know donuts have no nutritional value and will not help you have a good start. Regardless, you eat the donuts. You may have one donut, three donuts, or a whole box. This is because you are able to focus on your work due to treating yourself. That is an example of a personal type of cognitive dissonance.

Professional Examples

There are some professional examples as well. Figure 3 represents online shopping:

[Figure 3]

You are online shopping during your workday. You may say to yourself, "I never take any time off. This is a nice way for me to get away from my responsibilities and ultimately will help me to focus better. I always get my work done, so what is the big deal if I take some time to do online shopping?"

Another professional example is encouraging clients to do things that we do not do ourselves. Figure 4 represents a client taking their medications as prescribed:

[Figure 4]

We may think, “If this client does not take their medications, then they are in rough shape. For me, it is maintenance and prevention. I do not have it nearly as bad as this person does." We can get into a comparison space where we think that what we are doing is not nearly as bad as what they are doing.

What does this have to do with ethics? When we begin to self-justify, we may also see ourselves as a person who has high standards and is worthy of being a professional. The more we inflict these thoughts on other people, the more challenging it can be to see that what we are doing actually is a conflict. When we are confronted by evidence that we are doing something wrong, it is human nature to not change our point of view. Instead,&