Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Respiratory Concerns for the Premature Infant, presented by Tina Pennington, MNSc, RNC-NIC.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Examine two pathological lung conditions common in premature infants, including acute chronic phases.

- Compare contrast key points to improving positive pressure ventilation (PPV) utilizing Neonatal Resuscitation guidelines.

- Distinguish the role of multi-disciplinary team follow-up in the care of premature infants.

Introduction

- Premature birth refers to any delivery before 37 weeks gestation

- Its complications are the leading cause of newborn death in the U.S

- In the U.S. approximately 380,000 babies are born premature every year.

- 10.1% of total live births

- 1/10 babies are born too soon

- Depending on where you live or your race/ethnicity the rate can be higher

I always love to open up my talks with a few statistics that give you the scope of the problem I am discussing. Premature birth refers to any delivery before 37 weeks gestation, and its complications are the leading cause of newborn death in the United States. Some complications are cerebral palsy, learning disabilities, chronic lung diseases, blindness, and hearing loss, to name a few. In the United States, approximately 380,000 babies are born prematurely every year. One out of every ten babies is born too soon. That is one out of ten, too many. Depending on where you live or your race or ethnicity, that rate can be higher.

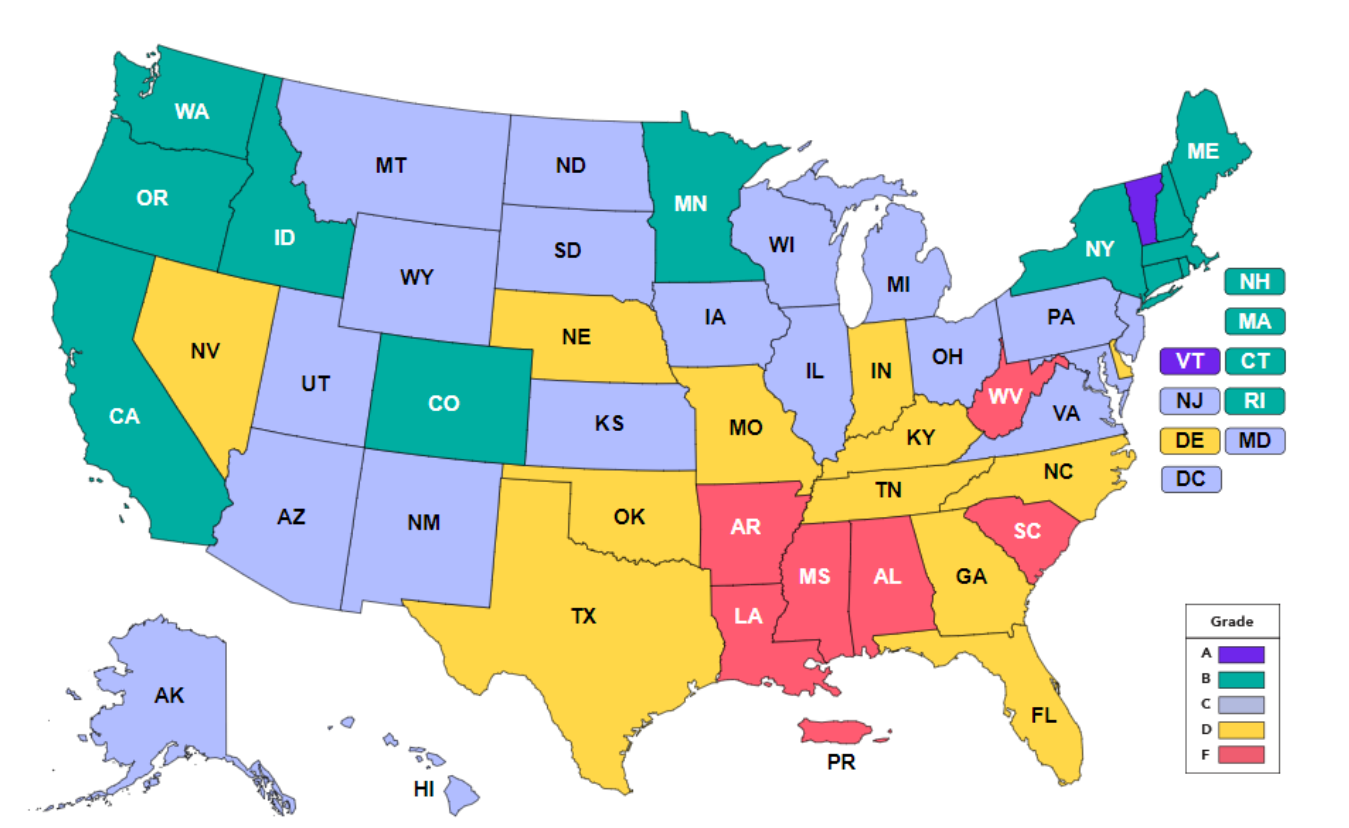

Figure 1. March of Dimes Report Card.

I love this map from the March of Dimes in Figure 1. It shows a grade. Here is your grading card. Your reds are your Fs, and your purples are your A's. I practice here in Arkansas, and it is an "F," which is sad for me. We need to find out what they are doing in Vermont. After all, Vermont is the only one with an A score, paralleling the maternal mortality map. Anytime you are having issues with maternal mortality or morbidity with the mother, you are going to have it with the infant. Much of what we do as professionals are to combat this, and some facilities out of California have studied maternal mortality. California has some good numbers, and they have lots of educational tools that we use to help combat prematurity and maternal mortality. They go hand in hand with the newborn diagnoses and treatment outcomes of the common pulmonary diseases.

Common Pulmonary Diseases of the Newborn

Diagnosis, Treatments, & Outcomes

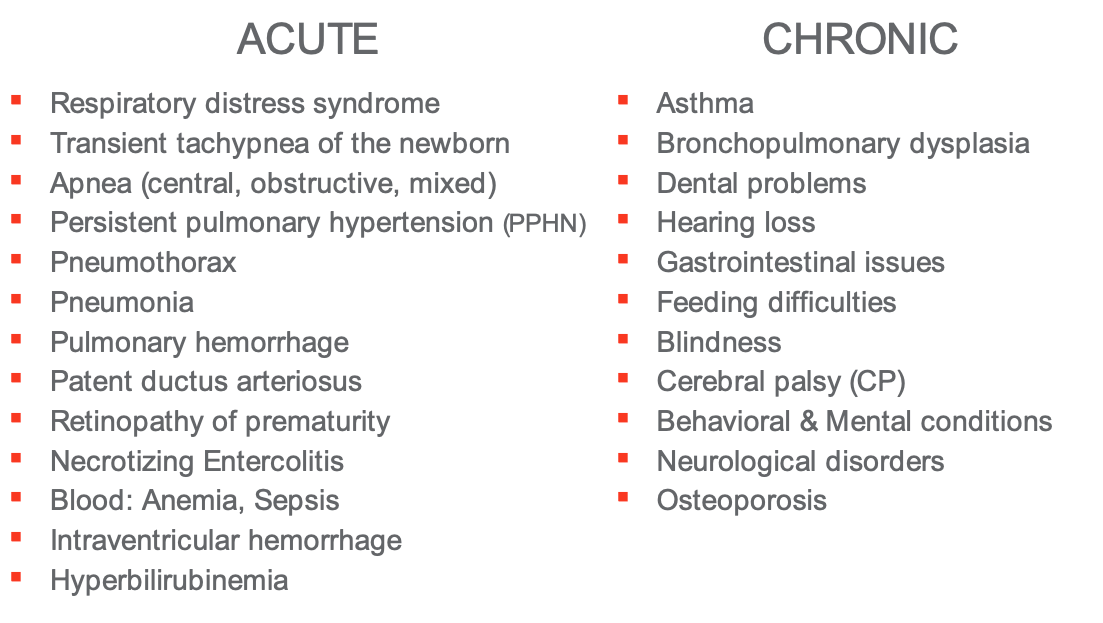

I will give a throwback to some of the disease processes, the treatments, and the outcomes. A more helpful explanation of why some of what our babies are doing and the pathophysiology behind some of these most common problems. You can see in Figure 2, there are many of them.

Common Diseases & Pathology Related to Prematurity

Figure 2. Acute and chronic diseases related to prematurity.

The acute problems usually happen to the babies in the early stages of development. Figure 2, covers all of the different courses of the body and different areas of pathology related to prematurity. Then as it becomes chronic, we get into the cerebral palsy, blindness, feeding difficulties, and neurological disorders. I will introduce you to some of the main ones and then what we can do to offset those.

Differentiating the Diagnosis

- Respiratory issues are the #1 cause for NICU admission

- Differentiating between the various disease process are important to ensure proper treatment & care (by all disciplines).

- Often determined by:

- Timing: some present immediately, within few hours, or later

- X-ray findings: some appear white or hazy, streaked or “ground glass, hypoinflation (RDS) or hyperinflation (TTN) or both

- Maternal history,infant’shistory

- Lookattheinfantasawhole

A crucial part is to diagnose and differentiate the diagnosis. To treat the disease properly, we need to know what we are treating. We know that respiratory issues are the number one cause of NICU admission worldwide. In utero, they are not using the respiratory system, as the blood is profusing out of the placenta. There is no gas exchange going on there. Suddenly, they have this physiological phenomenon going on when they take their first breath. Sometimes it does not work quite right. differentiating between those various disease processes interfering with the proper respiratory structure or physiology is very important to ensure that we get proper treatment, and this is by all the disciplines. Often it is determined by several different factors here. Timing is essential, as well as when the symptoms present. These things give you clues about what kind of disease process we are looking at.

Maternal history is important in an infant's history. Another thing is to look at the infant as a whole. Considering all of the mother's history, what is going on now? What was the birth like? Maternal history can give you a better clue about your diagnosis. Did the mother have diabetes? That will set you up for probably a week or two, lag in lung maturity, and glucose issues. You are going to have issues with feeding. Then another thing is other disease processes can mimic respiratory symptoms, which might not be your main issue. You have to figure out is there something underlying that we need to treat? The two most common things are infection and congenital heart disease. If you want to rule out infection, make sure that you draw complete blood counts, cultures, and CRP, which is a C-reactive protein test that indicates inflammation. Start antibiotics promptly if you suspect that there is an infection. Of course, cyanotic congenital heart diseases may have respiratory manifestations. An echocardiogram, an ultrasound of the heart, will give you a better clue about the heart's structure and function if that is causing the respiratory issue. If it is the heart, giving surfactant or putting the infant on the ventilator might not help the problem, because you need to treat that congenital heart defect.

Respiratory Distress Syndrome (RDS)

- Severity of chronic symptoms are often related to

- Gestational age at birth

- Severity of the RDS

- Treatment modalities (type of ventilator, medications, etc.)

- Level of Perinatal care (in-house birth vs flown to NICU)

- Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD)

- A serious chronic lung condition often related to damage to the lungs during the acute phases of RDS

Respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) is common at birth for premature infants. The first breath is an issue and does not get better. Does it recur within a few hours? That might mean you could have pneumonia, transient tachypnea, or other things. When your symptoms present, for example, aspiration, maybe the baby ate, choked, and then about an hour or later, we start to have respiratory issues. Chest X-rays are fun to look at and you learn a lot viewing them.

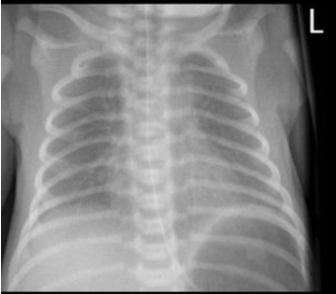

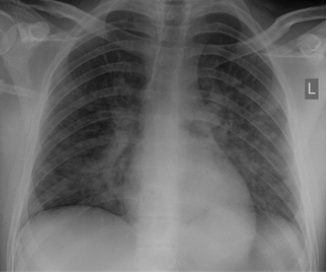

Figure 3. Respiratory distress syndrome (CC by SA 3.0 Wikimedia).

In Figure 3, RDS looks like "ground glass" with hypoinflated lungs, which means the air sacs are very close. There is not a significant expansion going on there. It looks like you have little shatters of glass all over.

Figure 4. Pneumonia (CC by SA 3.0 Wikimedia).

Figure 4, is a chest X-ray depicting pneumonia. The lungs are either hyperinflated or hypoinflated with air-trapping in one area, and then the air cannot get into another area, making for a very splotchy X-ray.

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation begins immediately at birth. The baby takes that first breath and starts having trouble. They will have tachypnea, retractions, nasal flaring, and grunting. They look like they are working to take every breath. "Grunting" is when the baby makes its own PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure), by trying to pop those little lungs open that is slammed shut, and sticky. Oxygenation and ventilation are not taking place, and the blood in circulation is not well perfused. The baby's skin is going to be mottled. They will have cyanosis, both central and acrocyanosis with increased pallor. They will be very pale. When we look at blood gases, they will have increased carbon dioxide (CO2) levels and respiratory acidosis. If respiratory acidosis is not corrected, it can be mixed with the metabolic component coming into play. I will say that when you are dealing with a child with an acute respiratory issue, such as RDS, you want to have access to arterial blood gasses, either through an arterial, umbilical, or a peripheral arterial line because you are going to need to check those oxygen levels. You want to make sure oxygen levels are going to stay within a normal range. You can monitor oxygen saturations with the pulse oximeter, however, to get the most accurate reading for these delicate babies, you want those arterial gases. Later on, when it comes to chronic issues, CO2 becomes the problem. By then you can do heel sticks for capillary gasses.

Treatment

Treatment for RDS is providing exogenous surfactant replacement. Surfactant is a thick protein and is the number one reason our premature rates are not what they were 50 years ago. The invention of surfactant in the late seventies made a difference in the viability of a baby born before 37 weeks. We will assist them with respiratory support and positive pressure ventilation through CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure). We will place them on the ventilator with an endotracheal tube, depending on what the child needs because we have gotten good at putting their surfactant in with the ET tube, then placing the baby on CPAP because surfactant is usually fast-acting. You can give the baby surfactant almost immediately, see a rise in the pulse oximeter, and improve your gases. Depending on what brand you use and what type you use, you will give one to two doses. We will also use antenatal corticosteroids, caffeine, supportive NICU care antibiotics, intravenous nutritional support, thermoregulation, and fluid electrolytes management, all are integral parts of treating respiratory distress syndrome in the NICU.

Outcomes

The severity of the chronic symptoms is related to the gestational age at birth. The number one determinant of respiratory severity is that the earlier the baby is born, the more severe the chronic condition becomes. The severity of the symptoms, treatment modalities, ventilators, and medications will also increase. Several decades ago, the old pressure ventilators breathed in-out and had set pressures. Usually, it gave you a PEEP, peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) with a rate. Those poor lungs were getting high pressures, causing barotrauma.

Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia (BPD)

Clinical presentation

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPG) is a severe chronic lung condition related to the damage to the lungs during the acute phase of RDS. The alveoli of the lungs do not oxygenate and ventilate as they should. It leads to increased carbon dioxide levels in the cells. Cells have a tiny window of normal carbon dioxide levels, usually 35 to 45, about 50 in a little premature baby, that is about it. Anything outside those ranges the cells do not act correctly and can cause issues. Sometimes it is tough to maintain carbon dioxide levels within those tight confines. As a result, pulmonary hypertension affects the flow of the blood into the lungs, then cor pulmonale, which is when you have right-sided heart failure related to blood pumping against the high pressure of those lungs. BPD is just not about the lungs either. It is like a syndrome. It covers a lot of different things. The impaired cellular function can lead to nutritional issues and make it very hard to keep the baby nutritionally balanced. They have many fluid imbalances. Fluid imbalances delay growth. They already have issues trying to feed, then you have the cellular function, which means the digestive cells are not working.

Treatment

The medical team will end up using many diuretics trying to keep these babies from gaining too much weight and edema. They tend to "third space" a lot with their fluids. You have to watch that. They are on steroids, which can delay their growth and increase their risk of infections.

Outcomes

In utero, babies tend to grow longer, their long bones get lean and long, and they may weigh eight pounds when they come out. Whereas a baby's bones born prematurely will not grow out as well outside of the uterus. It is challenging for us with total parenteral nutrition (TPN) or hyperalimentation to get their bones to grow as they should. Osteopenia is a considerable problem with babies, known as "rickets," where their bones are very brittle and do not grow. You end up with these little short, fat babies. When you see how they look, you notice that they have skinny heads, long foreheads, fat cheeks, and multiple chins because we are putting the weight on them, but we cannot make them grow longer.

Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn (TTN)

Clinical Presentation

Transient tachypnea of a newborn (TTN) is a benign, self-limiting lung condition that usually presents within a couple of hours of birth. The baby may come out breathing okay. As the day progresses, you start hearing some grunting and the baby does not want to eat. Usually, you will see TTN with your late preterm infants, those 33 to 37 weeks. Generally caused by a delayed clearance of fetal lung fluid and can be secondary to a C-section without labor or maternal diabetes. As the baby gets older and prepares for delivery, it goes through a diuresis phase, getting rid of much of that fluid. If the baby does not go through that phase, that fluid is still sitting in the lungs. You may want to consider some lab work to make sure that you do not have sepsis, and an echocardiogram to make sure there is no congenital heart defect, but these babies do pretty well most of the time. They will have tachypnea, mild nasal flaring, grunting, and retracting. The x-ray itself looks significantly streaked. It will be hyperinflated, which means the ribs are further apart than they should be. The chest may be slightly barrel-chested. The breath sounds are as expected. However, depending on their severity, you might hear some crackles and diminished or muffled breath sounds.

Treatment and Outcomes

Treatment is mainly supportive here, using a nasal cannula or CPAP. Rarely do they need to be intubated. Usually, we can keep their pulse oximeter in the nineties with less than 30% oxygen. Then, of course, routine NICU care, monitoring thermal environment, and IV access following with ABGs.

Apnea of Prematurity

Apnea of prematurity is frequently seen in infants born before 28 weeks, but it can also occur in term infants. It always worries me when you see apnea occur in term infants because that usually indicates a brain injury when they do not have that drive to breathe as they should. Formally, apnea is defined as sudden cessation of breathing that lasts greater than or equal to 20 seconds and is accompanied by: bradycardia, low heart rate, oxygen desaturations, or cyanosis in a child younger than 37 weeks gestation. There are three types, central, obstructive, and mixed apnea.

Types of Apnea

Central apnea is when the brain's respiratory centers forget to trigger you to breathe. There is no respiratory effort made. Again, when this happens in a term baby, something is going on there.

Obstructive apnea is when something is obstructing your breathing. Tracheobronchomalacia is an example of what could cause obstructive apnea. Other causes include the premature baby's poor muscle tone, pneumonia, or Croup resulting in secretions blocking airway movement. Maybe the baby was intubated in the past and the vocal cords were damaged. Congenital anomalies, for example, Pierre Robin syndrome, where the chin is small and the tongue is oversized in comparison, can all cause obstruction. Alternatively, babies are obligate nose breathers. When they have blockages in the back of their nose, they will not open their mouth to breathe unless you make them open their mouth.

You will see mixed apnea in many babies because they will lose the effort to breathe. The brain will tell them, to not breathe, and they will stop breathing for a second. However, because of their low muscle tone, vocal cord damage, or poor reflexes, those pliable tiny thoracic cages cannot recover from it. They cannot catch their breaths like adults. Adults who are not breathing for a second or two can catch their breath. The babies are not able to do that. They cannot do that "big gasp." Their vitals will drop, and you will have to stimulate them and get them back to breathing. When we have premature babies with apneic spells, we always chart the frequency. How long did the duration last, and did the baby's heart rate drop? Did the baby desat? Did the baby require stimulation to take a breath, or was it able to self recover? Those are all necessary details that the doctor will want to know because if that baby has constant apnea where you have to stimulate them all the time, the infant probably needs more respiratory support, such as CPAP or even intubation at that point.

Treatment and Outcomes

Methylxanthines are central nervous system stimulants to keep respiratory centers roused to breathe. You do not drink coffee before you go to bed, expecting to get a good night's sleep. When I first started back in the nineties, we used Theophylline. The babies stayed tachypneic. You had to give it three times a day. If the heart rate was over 160, it was contraindicated, however, if you did not give it, they would not breathe. Then we switched to caffeine. Caffeine is a fantastic drug. It is dosed once a day. We chuckle as we give them their little "afternoon cup of tea or coffee." It keeps them roused enough that it does not have side effects. It is naturally derived from the cocoa beans, much less strenuous than the old-time Theophylline was. We also use CPAP to help with that obstructive apnea. Remember, if they are sticky when breathing out, those lungs will collapse, then it is tough to get them going. Usually, we put them on a CPAP of five, and it leaves a little bit of cushion in the lungs. It makes that next breath easier to take. CPAP does not make you breathe but makes it easier to breathe. Easier to take that next breath of air.

Pneumothorax

Clinical Presentation

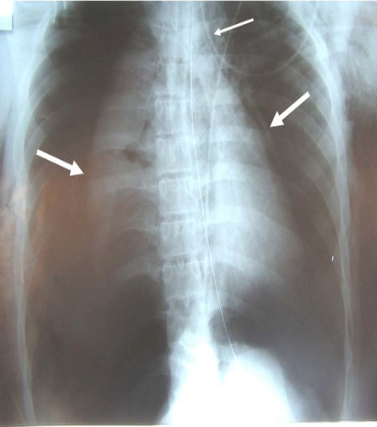

Next, we talk about pneumothorax or a pulmonary air leak. For some babies, a pneumothorax happens quickly and will go into respiratory failure pretty fast. Figure 5 is a chest X-ray illustrating bilateral pneumothorax, also known as pulmonary air leak syndrome or collapsed lung.

Figure 5. Chest X-ray showing a pneumothorax (CC0 Wikimedia).

A pneumothorax is often a side effect of mechanical ventilation (think of the older pressure ventilators). A pneumothorax occurs when air is trapped around or outside the lung in your pulmonary cavity. The dark, "hyperlucent" areas are the pneumothorax in Figure 5. The anterior-posterior and lateral positions with the affected side up will be more visible as air rises up. Clinical signs involve respiratory distress/failure, chest wall asymmetry, and diminished breath sounds on the affected side. The pressures in the cavity are greater than the pressure in the lungs causing partial or full lung collapse. The pliable section is now stiff, and the heart cannot pump as it should. You will have what we call circulatory or peripheral issues. The infant will be very pale and not have good blood pressure because cardiac output is impaired.

Treatment and Outcomes

The key to treatment here is to equalize those pressures—usually needle aspiration or chest tube insertion. Depending on the infant's size, we can sometimes use a 100% nasal cannula or Oxyhood. You may have to insert a chest tube between that fourth and fifth rib, draw some of that air out or connect it to a negative pressure device to allow for healing.

Persistent Pulmonary Hypertension (PPHN)

Clinical Presentation

Let's talk about persistent pulmonary hypertension (PPHN), and increased pressures in the lungs. When the infant takes their first breath, the lungs should drop systemic blood pressure, and heart pressure increases. Increased lung stiffness is caused by decreased oxygen, trauma, mechanical ventilation, pneumonia, RDS, BPD, and meconium aspiration. All those issues interfere with oxygen in the lungs, think of oxygen as a vasodilator. The best way to explain it is when the right side of your heart is trying to pump blood into the vein, it gets tighter and smaller. The pressures in those lungs are high, and the blood will not flow there. It is going to flow back the other way. We call that right to left shunt. The blood builds up in the right side of the heart, and the heart must pump harder against those lungs, causing cor pulmonale. The number one reason you have a child on home oxygen, especially if they are on very low, like 100%, half a liter, is usually due to right-sided heart failure or cor pulmonale. The right to left shunt will allow the blood to pool in that right ventricle. In utero, we have a patent ductus arteriosus. During fetal circulation, only about 10% of the blood goes through the lungs at any given moment because the gas exchange has taken place in the placenta. When you take that breath of oxygen, you begin the respiratory system very soon after birth, and the ductus should close.

If there is increased heart pressure, sometimes the ductus will pop open. It allows deoxygenated blood to exit through the aorta into circulation without going through the lungs. Now you have lower circulation, and it becomes a vicious circle because the more it happens, the lower the partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2) in the blood will be. We put the pulse oximeter on the right hand, measuring "pre-ductal" because the branch off the aorta that feeds the brain also feeds the right hand. It is the blood that has come from the lungs. It gives you a good idea of what is going on in the brain. If you do a "post-ductal" pulse oximeter read where the pulse oximeter is usually on the feet and has lower reading, it tells you there is blood going in the wrong direction. It is a vital tool to treat persistent pulmonary hypertension, identifying a shunt.

Treatment and Outcomes

We need vasodilators, something to dilate those lung tissues. Usually, we can dilate with nitric oxide and 100% oxygen. We will often allow the PaO2 on the blood gas to climb into the 300s before we start weaning to help dilate and relax those blood vessels. We also use various sedatives, analgesics, and paralytics to relax the babies because they will fight the vent, especially if it is a bigger baby. We want them as calm as possible. We provide minimal stimulation and a dark, quiet environment. Anything to help them relax to allow the lungs to reoxygenate and help the pressures come down because the adverse outcomes can lead to chronic asthma, BPD, persistent pulmonary hypertension, and cor pulmonale where the baby ends up on oxygen. At this point, let me say something about keeping that baby warm. I cannot stress the importance of keeping that baby warm because one of the side effects of hypothermia is persistent pulmonary hypertension. It will make your lung pressures high, developing into PPHN. Everyone can do all the resuscitation in the world and give all the meds, but if your baby is cold, it will create a metabolic acidosis that you cannot overcome.

I cannot stress to you the importance of keeping that baby warm. Get the warmer out, get it on the mother's chest, something to keep the baby warm. Many of your local hospitals, even level one and level two nurseries, are more comfortable caring for these babies. That way, they are at the hospital with their mother. If it is a very mild case, they can keep the baby on a low-flow cannula or a pulse ox and let the baby breastfeed. The baby will not get much food that way, but it keeps from breaking up the maternal diad and the baby rushing off to the hospital 100 miles away.

Maternal Drug Use in Pregnancy: Outcomes

Clinical Presentation

I started in the NICU in 1998. We had maybe one or two drug-addicted babies per year. Now, there are anywhere from 10 to 15 at a time probably. They cry and produce diarrhea until their skin is scorched, the nasal passage is snotty, and they do not eat well. There are tons of things that go on with them.

Treatment and Outcomes

Detoxing or "NASSing" (Neonatal Abstinence Scoring System) a baby is not a fun thing to watch. It usually occurs three to four days after birth. These are the babies who may go home before they start detoxing. That may be something that you might see. They are at risk for neural tube defects, congenital heart defects, gastroschisis, miscarriage, preterm delivery, and stunted growth development. Cocaine use is linked to placental abruption, which can cause neonatal hypovolemia or hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, leading to serious brain injuries. Smoking in the home dramatically increases the risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Mostly you are going to see developmental, neurological, and cognitive issues. Their lung issues might be secondary to congestive heart defects or preterm delivery. Alternatively, you can also have apnea related to hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, which does cause brain damage and is a leading cause of cerebral palsy—some pathology that many babies may endure. I pulled out some of the most concerning acute issues that you will see that will turn into issues and why you may be doing follow-ups with the baby.

Clinical Concerns

Positive Pressure Ventilation

- PPV is often not done correctly

- Technique

- Breath 2-3, breath 2-3

- Rate of 40-60 breaths/minute

- PIP of 20

- PEEP of 5

- Timely manner

- Dry, stimulate, remove wet linens, suction, position and assess heartrate with stethoscope

- If heart rate <100 begin immediately

- When PPV begins STOP stimulation

- Place pulse ox to monitor heart rate

Positive pressure is often not done correctly. People struggle with the Ambu bag. They tend to push too fast and want to jump right into chest compressions. I tell everybody to stop themselves when they get ready to start doing this. Take a breath, drop your shoulders think of your rhythm. Breathe two, three, breathe, two, three, breathe, two, three. We do not breathe in so quickly when we breathe, and time in is much shorter than our time out. You want to breathe at about 40 to 60 breaths per minute. You do want to watch your manometer. You squeeze your bag when you let go of the bag, and you do not want it to go to zero, but keep a PEEP of five, a PIP of 20, and follow the steps in NRP promptly. You want to dry, stimulate, remove your wet linen, suction, and assess that heart rate immediately. Start your positive pressure ventilation (PPV) when the heart rate is less than 100 or the baby is gasping or apneic. That is one of the issues that we have. PPV is either not done correctly or not done on time. We are thinking about brain cells here. Place the pulse ox on the right hand to monitor the heart rate. You are not monitoring the pulse ox as much as you are the heart rate on that right hand.

- At 15 seconds reassess heartrate, breathing

- If <100, apneic or gasping > start MR SOPA

- M–Mask

- Right size?

- Good seal?

- R–Reposition

- Neck role for sniffing position?

- Head in midline

- S–Suction

- Bulb or delee

- Mouth then nose

- O–Openmouth

- P–Pressure

- Increase PIP to 23-25 for a few breaths

- A–AlternativeAirway

- Laryngeal mask or ETT

After about 15 seconds of initiating PPV, you notice the baby is not coming up. Your heart rate is still down, and the infant is still gasping. Let's start MR SOPA, a set of corrective measures to ensure we are doing adequate positive pressure ventilation. You cannot resuscitate a baby with that chin on their chest. You have to get the baby in a sniffing position, use a rolled towel under the shoulders, position the head in midline, and suction their mouth and nose. I always open their mouths as babies will not breathe through their noses. If there is a blockage, you need to get that mouth open so they can breathe. Your PIP should be about 20, but sometimes it takes a little extra, 23-25, to get those airways open. Now you do not want too much pressure because you know what will happen, and it usually results in a helicopter ride and much paperwork. We do not want to go there. At this point, is your alternative airway, when you will put in either a laryngeal mask or your endotracheal tube. Please establish an airway before starting chest compressions, as most respiratory concerns are fixed with effective PPV and airway. Ninety-nine times out of a hundred, you never have to go to chest compressions with babies if you get an airway.

Overview of NRP 8th Edition Practice Changes

The neonatal resuscitation program (NRP) will always include "ABC," airway, breathing, and circulation. If you have ever taken a BLS test, they ask you, "What is the first thing you will do?" You will look for an airway for a baby because you are trying to get air into something that has never had air before. Give yourself 30 seconds to assess a heart rate rise once you get an airway. If the heart rate is less than 60 with an airway, turn the Fi02 to 100% and begin chest compressions.

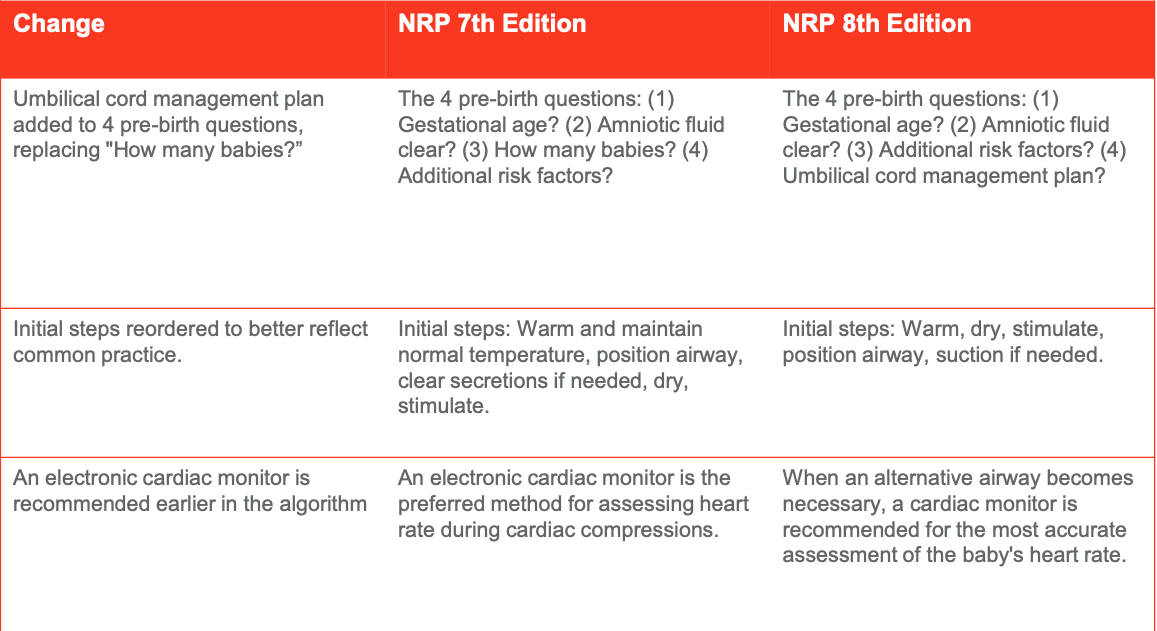

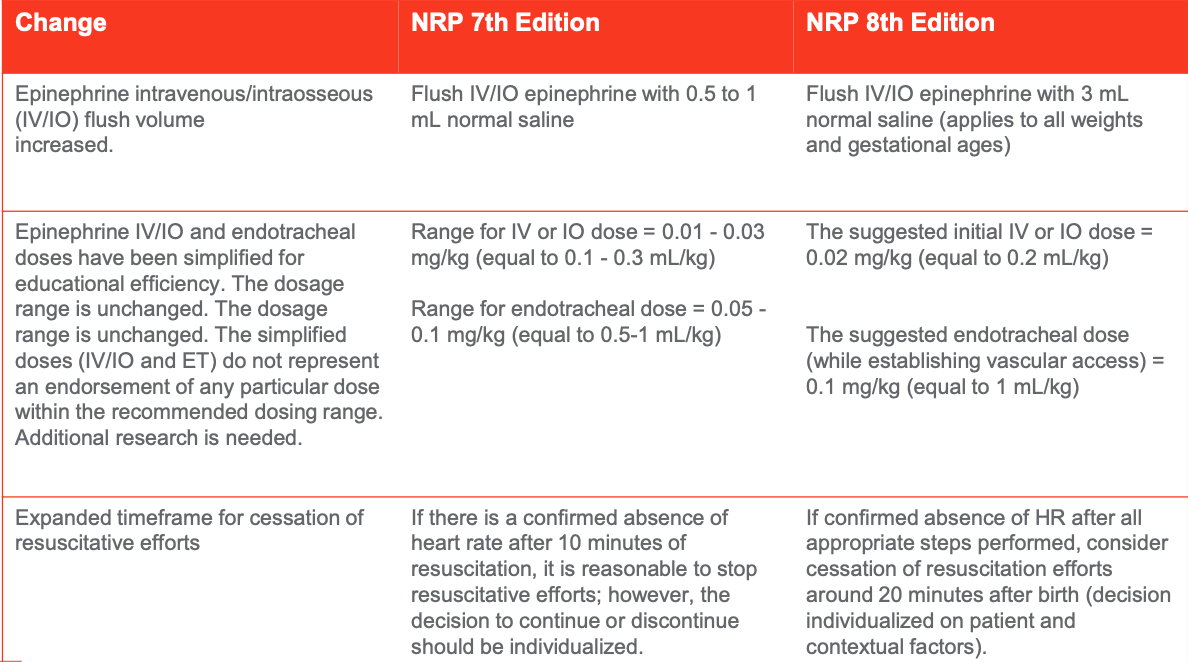

Figure 6. NRP 8th Edition Practice Changes (Adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021).

Figure 7. NRP 8th Edition Practice Changes (Adapted from the American Academy of Pediatrics, 2021).

There are a couple of changes from the seventh to the eighth edition of the NRP (Figures 6 and 7), including one of the questions about gestational age and clear amniotic fluid, how many babies, and additional risk factors? Now, NRP wants you to know umbilical cord management and how many babies will fall under the risk factors because it is a risk factor, to have a twin or triplet delivery (Figure 6). With the umbilical cord management plan, will you delay the cord clamp? It is essential in a preemie because you can increase their blood volume by up to 30% and decrease the need for extra blood. Giving the baby blood allows about 60 seconds of active blood to flow into the baby from the placenta before you clamp the cord. It is not gravity-driven. The placenta still has the heartbeat, and it is still connected. You do not need to hold the baby down. It is going to go in actively. They streamline the initial steps, warm, dry, stimulate, position the airway, and suction. Then they want you to put the cardiac monitor on sooner. In the seventh edition, they wanted it on before you started chest compressions, and in the eighth edition, they want it on if you need an artificial airway. If you have to intubate, put the baby on a cardiac monitor.

We would flush IV epinephrine with 0.5 to 1 mL of normal saline with the seventh edition. Now they want all weights and gestational ages of babies to be flushed with 3 mL of normal saline (Figure 7). Almost like you are giving a little saline bonus to the baby. When you gave epinephrine in the seventh edition, they gave you a range of doses, but now a suggested dose needed is given in the eighth edition. They want you to give the initial IV dose at 0.2 mL per kilogram. The endotracheal tube dose is suggested to be given while establishing vascular access. When giving IV/IO epinephrine through the endotracheal tube at 1 mL/kg, they have extended the amount of time they want you to attempt resuscitation from 10 minutes to 20 minutes. One thing we strive for in the NICU is to protect the baby's brain. It is delicate. Many little blood vessels can break. They are very susceptible to fluctuations in oxygen in their brain.

Neuroprotection of the Premature Infant

Neuroprotection is what we do, strategies capable of preventing neuronal death. We are trying to take care of those little brain cells. Babies born at less than 37 weeks are at significant risk of having intracranial ischemic or hemorrhagic injuries. They are at the greatest risk in the first 72 hours of life. Neuroprotection is strategies that promote optimal synaptic neural connections and supports normal neurological, physical, and emotional development along with preventing disabilities. You must understand that these babies are supposed to be still floating around in the quiet little dark, protected area. Suddenly, they are out here, and we are poking, prodding; the lights are on. It is cold or hot. The babies do not handle these wild stimulations well, resulting in many issues. We try to provide prenatal prevention. If there is any chance that this baby may deliver within the next six hours, we administer maternal corticosteroids and prompt antibiotic treatment for chorioamnionitis. If you suspect the mother has an infection, get those antibiotics on board, and transport them to a tertiary care facility. Perinatal prevention provides a higher level of care, with delivery in a hospital with a high-level care team. When you are in that higher-level care team's hands, outcomes are much better. Note that delayed cord clamping may be needed and pay particular attention to avoid hypothermia. Do not let the baby get cold.

The baby is here. What do we do for postnatal prevention? Promptly, start antibiotics if indicated and make cautious use of inotropes. Examples of inotropes are dopamine dopexamine, milrinone, and epinephrine. Inotropes increase the heart rate, improving cardiac output and blood pressure. What happens is that inotropes are usually hard to control. You will give them dopamine, and their heart rate will go sky-high. You can imagine those little blood vessels popping in their brains. Be careful using those. Sometimes you do not want the carbon dioxide fluctuations (CO2). You will have a CO2 of 60, and if you crank your ventilator down, you will have a CO2 of 30. Research is finding that a little higher CO2 is not as dangerous as fluctuating CO2 on a baby. Avoid rapid, significant fluid shifts, initiate neutral head positioning and provide care bundling. Bundling of care includes: feeding the baby, changing the diaper, turning the baby over, changing the bedding, sticking his heel, and drawing labs. You do whatever you have to do at once and walk away to provide minimal stimulation. We usually do that again for the first 72 hours of a preemie baby, where the room is dark. The bed is covered. We do not do anything more than what we have to do to that baby to decrease stimulation, letting those little nerve endings heal and develop properly.

Multi-Disciplinary Team Approach to Care

- They are at risk for

- Developmental & cognitive delays

- Behavioral difficulties

- Motor skills impairment

- Complex & chronic medical disorders

- Feeding and/or malabsorption issues

- Vision & hearing deficits

- Speech & language problems

It Definitely Takes a Village to Raise a Preemie

It takes a village to raise a preemie. Premature infants are at high risk for developmental & cognitive delays, behavioral difficulties, motor skill impairment, and complex chronic medical disorders. Babies develop what is called necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC). They can have bowel resections, feeding, and malabsorption issues, and we call that short gut syndrome. Many times there are vision and hearing problems. Retinopathy of prematurity is one of the leading causes of blindness worldwide. Many antibiotics will make them deaf.

Speech-language therapy can be excellent for these babies. We do so much to their mouth, including intubating and suctioning them, causing oral aversion to anything coming towards their mouth. The endotracheal tube causes the infants to develop high arched palates, leading to many speech-language development problems. They can become orally aversive to certain food textures they do not want to eat. They have trouble forming words. Lots of speech-language issues with these little guys need to be addressed by the specialists for the best quality of life. Most states have early intervention programs for NICU graduates. They have care management programs that help coordinate services. Know that each of these conditions needs to be treated. They need respiratory therapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, physical therapists, psychiatrists, and all kinds of things to help them become the best they can be as they grow. Also, services help the parents because it is often not what they signed up for.

Overstimulation Cues

Sometimes you will go into a house with a fussy, overstimulated baby. It is very easy to overstimulate a baby, especially if there are other children in the house or the household is noisy. Here are some cues to overstimulation.

Feels stiff (tense) or limp

- Will outstretch arms and spread finger apart (Splaying)

- Squirms, startles easily, or twitches excessively

- Avoids eye contact and/or turns head away

- Arches back while making a fist

- Skin will pale

- Frowns, fussy, cries

- Spits up or chokes easily

During your assessment and interventions, the baby may feel stiff or very limp. They will often outstretch their arms and spread their fingers, called "splaying." They will squirm, startle easily, or twitch excessively. They will avoid eye contact with you and turn their head away when you are trying to look at them. Arching is an important cue. They will make fists while they arch, especially when trying to change a diaper on a baby. They may bend backward, almost like the baby is trying to get away from you. Their skin will become very pale. They will frown, they will fuss, and they will cry. It may not even be a high-pitched, mad cry but a little whimper. They will let you know they are not happy. Then they will spit up and choke very quickly when they eat if they are nervous or upset.

Calming Techniques

Swaddling is a considerable technique, and swaddle blankets are fabulous. Now, this is up to three to four months old. After that, they do not want to be swaddled as much once they start moving around. Speaking softly to them, adding a pacifier, and dimming the lights are great calming techniques. Take them to a quiet place, a room alone, and place your hands slightly on their tummy. Allow them to hold your fingers, hold their hands, roll a blanket up, and put it under their feet or around them where they can feel it. They like to feel that pressure against them and then use gentle, firm pressure. If you are holding the baby, provide firm, gentle pressure. Never stroke, bounce, or pat an upset preemie. You are not shaking them up like a Polaroid. You want to hold them still. Even when they are lying on the bed, put one hand on their head and one hand on their feet—a calming effect.

Preventative Medicine

If you are treating the baby at home, the parents should have a piece of paper on the refrigerator that says if the baby's doing this, please call the pediatrician or call 911. That is important. If you are working with the baby and notice those symptoms, do not hesitate to get help. The problem with babies is that they cannot raise their hands and say, "My tummy hurts." You have to assess these subtle signs and symptoms to determine whether the baby is getting sick and should they need to go to the doctor. There is usually a parent or a caregiver that is in tune with the baby and knows before anybody that their baby is sick. If you have a parent or another caregiver in the house telling you that this baby is not acting right today, take them seriously. They usually know because the baby will be eating less than usual, have any changes in appetite, or cry regularly.

Again, it is not necessarily a high-pitched cry. It may be a fussy grunt. The baby cannot be comforted, is less active, or has any behavior change. Diarrhea or constipation are the extremes, usually loose, watery stools and vomiting. That means more than spitting up after they eat, usually projectile vomiting that lasts more than a few hours. Babies, especially premature babies can dehydrate very quickly. The baby may have a high fever of 100.4 or higher, seeming more than the mildly ill, vomiting with the fever, a rash, a cold, and trouble breathing. Call 911 if they look blue around the lips or throat. Some signs are subtle, and some of them are not.

Vaccines are essential for the prevention of diseases. Childhood immunizations for all children in the household are important. Common spreadable diseases include respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Make sure even the adults have their Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) boosters, and flu shots for everybody. Sometimes parents will say no visitors, especially during the flu season. Smoking in the house is dangerous. The house must maintain a degree of cleanliness, an environment in which a respiratory-challenged baby can live. They cannot live in a dusty, smokey, dirty house. It does not work that way.

Safe Sleep

The last thing I do want to mention is safe sleep. Notice how the baby is sleeping, assist them, and know the importance of being alone in the bed, on their back in a crib, sleeping on the couch, on the recliner, or on daddy's chest is not going to cut it. I have been to several conferences with parents who have lost their babies from things like this. They recommend no bumpers, loose bedding covers, wearable blankets, and fitted pajamas to help. There is lots of information out there for the parents on safe sleep.

References

Altimier , L., Phillips, R. (2016). The neonatal integrative developmental care model: advanced clinical applications of the seven core measures for neuroprotective family - centered developmental care. Newborn Infant Nursing Reviews 16(4), pp. 230 - 244.

Graven, S, Browne J.V. (2008) Sensory development in the fetus, neonate, infant: introductions overview. Newborn Infant Nursing Review, volume 8, pp. 169-172.

Jha, K., Nassar, G. N., & Makker , K. (2021). Transient Tachypnea of the Newborn. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing: Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537354/

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine (2022). Neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. Retrieved from: https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/001563.htm

National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine (2022). Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Retrieved from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/healthtopics/bronchopulmonary-dysplasia.

National Birth Defect Registry (n.d.) Premature Births. Retrieved on 01/30/2022 from: https://birthdefects.org/prematurebirths/?gclid=Cj0KCQiAi9mPBhCJARIsAHchl1z3YW5TqskSd5T Aiy1XVTiqjHkfY9DgNtAziU3BVDuKNcwsoBH5mKYaAkxkEALw_wcB

Murthy, P.,et al. (2020). Neuroprotection Care Bundle Implementation to Decrease Acute Brain Injury in Preterm Infants. Pediatric neurology, 110, 42–48.

Pennington, T.C. (2022) personal photos from my Iphone.

Ryan, M., Lacaze - Masmonteil, T., & Mohammad, K. (2019). Neuroprotection from acute brain injury in preterm infants. Paediatrics & child health, 24(4), 276–290.

Yadav S, Lee B, Kamity R. Neonatal Respiratory Distress Syndrome. [Updated 2021 Jul 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK560779/

Kondamudi NP, Krata L, Wilt AS. Infant Apnea. [Updated 2021 Nov 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441969

Citation

Pennington, T. (2022). Respiratory concerns for the premature infant. Continued.com - Respiratory Therapy, Article 143. Available at www.continued.com/respiratory-therapy