Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, The Registered Nurse and Respiratory Therapist Alliance: Identifying and Assessing Acutely and Subtly Declining Patients, presented by Nancy Nathenson, RRT.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Recognize the benefits and elements of a team approach in the identification and assessment of the declining patient.

- Identify the patient criteria for initiating a rapid response with RN/RT team assessment on an acutely and subtly declining patient.

- Describe the essential information needed to accurately report patient assessment findings to the medical provider.

Teams to Improve Outcomes

I want to talk first about outcomes because Rapid Response Teams (RRT) have been known to improve outcomes across the board. A study by Cassidy (2020) took place in an urban academic and safety-net hospital. A multidisciplinary team developed a strategy to reduce pulmonary complications post any general or vascular surgery that took place in the hospital. They had defined criteria and engaged the team to intervene in a number of ways. It was called the I COUGH.

- Incentive spirometry

- Coughing and deep breathing

- Oral care

- Understanding (including patient and clinician understanding of the protocol and the necessity for it)

- Getting out of bed at least three times daily

- Head of bed elevation

They gathered their data one year prior to implementation and then one year post-implementation of this program. There were over 1,500 patients evaluated. They found that in patients with post-operative pneumonia, during pre-implementation there were 2.6% of the total patients and total post-implementation was 1.6% of the total.

They also looked at unplanned intubation. During pre-implementation it was 2.0% and post-implementation it was 1.2%. This study, which occurred over a period of about six years, involved a Rapid Response Team (RRT) in a PICU with the goal of reducing mortality and morbidity in unplanned admissions. After the RRT implementation, they discovered a 28.7% reduction in pediatric risk of mortality and illness severity, a 19% reduction in PICU length of stay, and a 22% decline in mortality. In addition, the relative risk of death after the Rapid Response Team implementation was less than 1%. This was a great success.

This also led to an earlier capture and aggressive intervention in the progression of the decompensating pediatric patient. We know that teams improve outcomes. The data is somewhat inconsistent across facilities based on what outcomes they actually do measure and how to measure them. There is a wide array of different types of Rapid Response Teams, such as advanced or difficult airway teams, pulmonary embolus teams, and diabetes CHF. We are going to talk specifically about acute and post-acute rapid response for the declining patient today.

Serious Adverse Events (SAEs)

Hippocrates was known as the father of medicine. He said, “Primum non-nocere,” which means first do no harm. He was very smart. He knew that when you're caring for a patient or someone that is sick, your tenant and the first thing that you do is to do no harm. Unfortunately, we have serious adverse events that can cause a failure to rescue. A failure to rescue is when we simply fail to respond in an appropriate or timely manner to patients that are deteriorating. Some of the conditions that are associated with failure to rescue are when patients experience respiratory failure, hypotension, consciousness changes, arrhythmias, pulmonary edema, or sepsis and we aren’t recognizing them.

Serious adverse events are a result of the failure to rescue and are unexpected, but they are common. There are iatrogenic reasons these adverse events occur, which is when illness or injury is caused by medical intervention or treatment. The types of iatrogenic interventions that patients may undergo include diagnostic aspiration of fluids that can lead to hemorrhages or secondary infections. Rapid pleural or peritoneal fluid aspiration or even needle biopsies can lead to shock and even death. Another cause is adverse drug reactions. Some of the most common outcomes for serious adverse events are cardiac arrest, unplanned ICU admission, and unexpected death. This is a big problem because we're not identifying these patients and what's happening with them.

Warning Signs

Multiple studies have documented warning signs about serious adverse events, such as abnormal vital signs present within an hour to one day prior to these adverse events. Measuring vitals often and accurately is very important. This shows us that there are opportunities to intervene when we have gaps in knowledge. Recognition and response to abnormal vital signs or lab tests may be limited in reliability and in their quality. There could be triage mistakes, a delay in physician notification, or failure of physician presence. Inadequate assessments may occur or failures to seek help. Another thing is there can be differing views among staff on the urgency of patient symptoms.

Respiratory rate is the most reliable predictor of complications within 24 hours of serious adverse events. Respiratory rate is not always optimally measured because clinicians other than respiratory therapists don't always optimally measure respiratory rate. Non-invasive monitoring is really important when we're looking for those warning signs. Objective criteria will be key with the expertise and equipment needed. We want to look at numbers and actual objective criteria or objective results when we're identifying a declining patient.

Studies by Schein et al. (1990) and Franklin and Mathew (1994) found that patients showed a period of decline preceding cardiac arrest. Schein et al. (1990) found that 70% of patients showed evidence of respiratory deterioration within eight hours of cardiac arrest. Franklin and Mathew (1994) showed that 66% of patients showed abnormal signs and symptoms within six hours of arrest. In addition, the physician was notified in only 25% of the cases. This information makes it clear that Rapid Response Teams are needed.

100,000 Lives Campaign

Due to these serious adverse events, failure to rescue, and what was happening in our healthcare system, the 100,000 Lives Campaign was developed in 2006. It was launched by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) to significantly reduce morbidity and mortality in American healthcare. It is built on the successful work of healthcare providers all over the world. They introduced proven best practices across the country to help participating hospitals extend or save as many as 100,000 lives.

Within this campaign, 3,100 hospitals were enrolled, which was about 3/4 of all of the hospitals in the United States at the time. With the help of quality improvement organizations and hospital associations, they built a national infrastructure for change, with coalitions of organizations in every state to support change locally. They also had a network of 155 mentor hospitals. Over this 18-month campaign period, the program prevented 122,000 fewer needless deaths.

Six Goals of 100k Lives

There were six goals of the 100,000 Lives Campaign.

- Deploy Rapid Response Teams at the first sign of patient decline

- Deliver reliable evidence-based care for MI

- Prevent adverse drug events

- Prevent central line infections

- Prevent surgical site infections

- Prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia

Our care for MIs has been established for many years for our STEMI patients. This has been associated with prolonged survival and a lower risk of recurrent ischemic events. Regarding adverse drug events, one study concluded that medication reconciliation interventions designed to optimize medication use reduce the risk of any type of adverse drug event, including serious ones in older adults. They were very successful with that, especially in the elderly considering how many prescriptions they were on and all of the interactions that can occur. This is where having a pharmacist handy would be helpful.

Another goal was to prevent central line infections, which are placed commonly for patients that are going to need IV fluids and medications for a long period of time. The most common complications for CVP lines are infection, thrombosis, and malposition. The symptoms that a patient might manifest include engorgement of neck veins, discomfort with infusion, sudden chill and high fever, becoming tachypneic, and having hypotension. Preventing surgical site infections is another goal of the 100,000 Lives Campaign. One intervention is called the FAST-HUG concept. That was when they had daily evaluations of feeding, analgesia, sedation, thromboembolic prevention, head of bed elevation, ulcer prophylaxis, and glucose control in critically ill patients. This was completed in the surgical ICU. Preventing ventilator-associated pneumonia included elevation of the head of the bed to 30-45°, daily sedation vacation and assessment of readiness for extubation, peptic ulcer disease prophylaxis, and deep vein thr5ombosis prophylaxis. These things were employed across Rapid Response Teams throughout the US.

5 Million Lives Campaign

The 5 Million Lives Campaign followed the 100,000 Lives Campaign. Their goal was to support all of the benefits and outcomes of the 100,000 Lives Campaign, by way of the following:

- Prevent harm from high alert meds

- Reduce surgical complications

- Prevent pressure ulcers

- Reduce MRSA infections

- Deliver evidence-based care for CHF

- Get boards on board to be more effective in accelerating the improvement of care

Four Key Elements to Rapid Response Teams

When we think about rapid response, there are four key elements.

- Early detection

- Response triggering mechanism

- Predetermined rapid response team

- Rapid intervention

We need a way to detect difficulties in our patients early. We need to have a response triggering mechanism for how to call the team. We want to have a predetermined, Rapid Response Team so that at the beginning of a shift, everyone knows who is on that team. Rapid intervention is also key. Another very important component is administrative support. Administrative support needs to be able to supply us with the resources, organization, and a process to evaluate how we're doing, our outcomes and to promote improvement to prevent future events.

Rapid Response in Acute Care

The Rapid Response Teams (RRT) in acute care may have different names. Sometimes they're called the Medical Emergency Team (MET) or it the critical care outreach (CCO) team. Some hospitals name their own with the facility name and Rapid Response Team. The titles of the teams may differ, but the basic idea is that they are going to be outlining the management of patients who have been identified as being in a threatening situation. A threatening situation is defined as a system or multi-system failure that is evidenced by a change in the level of consciousness, respiratory distress, or cardiac changes. Those are the general failures that we are looking at.

RRTs have evolved to address even more specific conditions such as difficult airway teams. The teams vary upon the members, depending on if you're in an acute versus a post-acute team group. The team may include the physician, pharmacist, and anesthesiologist just to name a few.

Rapid Response Criteria

For acute care, rapid response criteria include when a staff member is worried about the patient. We all have intuitiveness about our patients. We have our gut feeling about something that might be going wrong with the patient. That in and of itself is one of the criteria to call the Rapid Response Team. Any one or more of these criteria would trigger the Rapid Response Team.

- Staff member is worried about the patient

- Acute ∆ in HR < 40 or >130

- Acute ∆ in systolic B/P < 90 mmHg

- Acute ∆ in RR <8 or >30 bpm

- Acute ∆ in SpO2 < 90% despite O2

- Acute ∆ in conscious state

- Acute ∆ in UO to < 50 ml in 4 hrs

The criteria above are for acute care and looking for an acute change in multiple different factors. Examples of changes include a heart rate of less than 40 or greater than 130, a change in systolic blood pressure less than 90 millimeters of mercury, respiratory rate of less than eight or greater than 30, and SpO2 of less than 90%, despite giving oxygen enrichment. Other criteria include an acute change in the conscious state and a change in urine output to less than 50 milliliters in four hours. There are additional criteria that do occur in some facilities which focus on unrelieved chest pain, a threatened airway, seizures, and uncontrolled pain.

Rapid Response Interventions

How do we intervene for these patients in acute care when they display these types of abnormal vitals and show acute deterioration? If we anticipate that they had a stroke, then initiate the stroke team and stroke orders. If we anticipate sepsis is the issue, then initiate the sepsis protocol, including drawing labs and starting antibiotics. If we suspect an MI, get a 12 lead and consider MONA, the acronym for morphine, oxygen, nitroglycerin, and aspirin. If we see that they're hypovolemic, resuscitate them immediately. If they have respiratory distress, identify what is the cause of the distress. Manage the airway, including suctioning and supplement with O2. If there is oversedation, immediately deliver Narcan and apply airway management. Some of the most common interventions for Rapid Response Team intervention include O2, IV fluids, diuretics, bronchodilators, labs, and x-rays.

Post-Acute Care (PAC)

Post-acute care includes rehabilitation, long-term acute care hospital, acute rehab, ventilator assist unit, special needs, pediatric rehab, and transitional care, which was our skilled nursing. We had all those levels of care within our post-acute facility.

Response Criteria

While researching this topic now and in the past, I found that there were next to no examples of post-acute rapid response where we identify the subtly declining patient. Therefore, we modeled our criteria after the acute care criteria. You'll see that we have the absence of “acute” in any of our criteria.

- “Something is just not right”

- Mental status changes

- Significant ∆ in vitals (HR, RR, B/P, T°, Pain)

- ↑ O2 needs

- ↓ Activity tolerance (≥ 2 missed therapies in 12-24 hrs)

- Unrelieved pain

- Significant weight gain ≥ 1 lb/day

- Changes in LAB values

Our criteria began with the same type of thing. Something's just not right. What is our gut instinct telling us about the patient? Also included are mental status changes, significant changes in vital signs, or increased O2 needs. If we had a patient that was on room air and suddenly, they're on two liters of O2, this would be criteria to call what we call the PACE team. PACE stands for presentation, assessment, collaboration, and evaluation.

Other criteria included decreased activity tolerance where a patient missed two or more therapies in 12 to 24 hours and unrelieved pain. Rather than the CCs per hour for INO, we looked at the significant weight gain of one pound or more per day. Any changes in lab values that were significant were also criteria for response. Respiratory and oxygen needs, missed therapy, along with changes in vital signs were the most common reason for the return to acute care. We found we needed to intervene earlier when we identified these things happening.

The RN/RT Alliance

I worked with the chief nurse educator and an LTACH (long-term acute care hospital) charge nurse to developed the criteria and start our PACE (presentation, assessment, collaboration, and evaluation) team. Our PACE team included an RT and an RN from our LTACH because they were very experienced and were usually the staff that took care of patients that came directly to us from the ICU. The RT didn't necessarily have to be from LTACH. When you look at the team concept, two heads are definitely better than one. The RNs often provide us with a holistic multi-system view of our patient and the RTs have the expertise in pulmonary assessment.

Teams may vary, depending on your facility. They might include physicians, hospitalists, anesthesiologists, nurses, RTs, and sometimes pharmacists. Creating this team promotes collaboration and critical thinking. In some Rapid Response Teams, for example, in acute care, they may have an RN and RT actually assess the patient and assess the need to call the team. There are lots of variations in how that process works.

Critical Thinking

We can't talk about teamwork and patient care without discussing critical thinking. That is a big focus of respiratory and nursing schools everywhere. Critical thinking is using prevention and health promotion to avoid any problems. We look at the best way based on current evidence.

Thinking is a skill. Learning how to think critically requires knowledge, insight, experience, practice, and feedback. Not all of us are at the same skill level with critical thinking. Some of us are not as experienced and some of us don't have all of the knowledge yet. However, we are responsible to be knowledgeable of extremely sophisticated equipment and technology. We have to adapt to a constantly changing body of knowledge. It can't rest on one particular person for all of this knowledge so we're going to use our team and colleagues to help us in these types of situations. The AARC standards state that the patient-centered care process serves as a critical thinking model that promotes a competent level of care. Schools work very hard to help create this competence in their students.

With critical thinking, whether you're working with one colleague or multiple colleagues, make sure you have clear and precise questions that you want to be answered. Identify if you're assuming things that are not based on any type of objective data. Make sure that you have credible sources and resources. Hold your focus on what the situation at hand is. Deal with the complexities of the situation. For example, you could have multi-faceted deterioration of a patient, not just a respiratory issue that we have to deal with. When there are more than two people on your team, it is considered to be a multidisciplinary team. Withhold judgment against individuals as you are assessing. Together, we must analyze and come up with a conclusion and a next step forward.

Critical thinking is a mental activity. We're going to evaluate individual’s arguments, propositions, and judgments of the situation. That is going to guide beliefs and our decision-making. Critical thinking requires the ability to:

- Prioritize

- Anticipate

- Troubleshoot

- Communicate

- Negotiate

- Make decisions

- Reflect

Let's take a closer look at all of these facets of critical thinking.

Prioritize

To prioritize means to look at what is expected of you in one particular day and what could be unexpected. For example, think about your workload and patients and reflect on whether all of your patients need therapy. Can any of them have changes in frequency or modalities? You also want to prioritize any change in condition that they may have and any emergencies that come up. Think about new patients that may be in the queue.

Anticipate

We also want to be able to anticipate, which is thinking ahead to possible problems. For example, when we change the care plan, how is that patient going to respond? Are they going to respond in an expected way, or will they respond in an unexpected way? We need to be able to see the big picture. When we have new patients, we are going to need their history. We need to know what their current status is and what kind of tech we're going to need available. We'll want to develop questions for the provider on what we need to know about the patient.

Troubleshoot

Troubleshooting is usually related to equipment. We first need to detect and locate the problem. When we find that problem, what resources do we have available? Are there manuals we need to access? Is there something easy, such as online resources that we can access? Sometimes equipment has troubleshooting menus and responses embedded within them. We need to look at the error messages and we may need to even consult another RT or colleague who is more experienced with that particular piece of equipment.

Get those resources and be able to deal with the situation. It is also important to remain calm in front of the patient’s family and colleagues. Have a systematic approach to the malfunction and be prepared to do whatever it takes to keep that patient safe in that situation.

Communicate

We all need to communicate in ways that are the most comfortable for us, but be clear and convincing. Sometimes it's more challenging to be clear and convincing in chaotic situations. We may need to speak more loudly than usual. Try to use the name of the person to get their attention in a chaotic situation, have eye contact, and be sure that we communicate with them what our question is or if we're assigning them a particular role. We want them to acknowledge that they heard the question or that they are going to complete that role.

Share information and be able to explain what's happening clinically, from our perspective to the nurses and doctor. There could be patient data that's conflicting or some insufficient data, which could make it difficult to analyze and evaluate a patient properly. Communicate with the patient when it is appropriate and keep them up to date on their situation.

Negotiate

We negotiate when we don't have the sole power or authority to do what we believe is right and best for the patient. Discuss the situation with others and try to influence them. We might use a question to phrase a suggestion. For example, do you think it would be a good idea to do switch to high-flow oxygen? We also want to be sure that we listen to each other when negotiating.

Decision-Making

Decision-making is when we determine what judgment or course of action is next. You may be doing that as an individual or with a group, such as a multidisciplinary team. This is where you think about what is happening and what you are going to do. If you are working with a multidisciplinary team, it’s important to ask questions of the team in decision-making.

Shared decision-making is a concept that includes the patient and the clinician who work together to decide what's best for the patient. That result would depend on what's needed, such as tests, treatments, and care plans. We want to balance the risks that the patient might undergo and any unexpected outcomes that might occur with any of these tests or treatments with patient preferences and values. Sometimes there are cultural differences to be thought about. For example, some individuals really trust the provider and want the provider to make all the decisions. Sometimes they don't want to participate, which is something to consider.

Reflect

Reflecting is when we look at ourselves inwardly and assess our opinions, assumptions, and any biases and decisions that we previously made. Think inwardly and learn from your problems and mistakes. Your ability to reflect is going to change over time and throughout your career. The best way that we can learn from our problems and our mistakes is to review the event with our team and debrief after it.

Next, utilize available resources. Gather intel from wherever we can get it. This includes staff members who consistently care for the patient, such as the primary nurse, RTs, other nurses, therapists, and nursing assistants. You can also gather information from physicians, nurse practitioners, PAs, and the entire response team. Evidence-based practices are another important resource that is constantly evolving. The National Guideline Clearinghouse has listed over 2,700 clinical practice guidelines. Each year, the results of more than 25,000 new clinical trials are published. There is no single practitioner that can handle, absorb and use all of this information. The need for specific knowledge in certain areas of care by different team members has become a necessity.

Tips for the Team

Here are some basic tips for working in a team.

- Introduce yourself

- Clarify roles

- Objective not subjective

- Address by names

- Be assertive as needed

- Closed-loop communication

- State what is obvious, do not assume

- Something not making sense? Gather perspectives

- With conflict, decide what is best for the patient

It’s important to introduce yourself, especially if you're walking into a room and you are in a different area of the hospital that day or you don't know someone in the room. Let yourself be known as to who you are and what your role is. We should have our name tags on, but sometimes we don't and we may just start going about our business. Clarify your roles within the team. Be objective, not subjective, when you are looking at your patient. Address each other by name, if you can, and be assertive when you need to.

Utilize closed-loop communication with each other. State what is obvious and do not assume that the others are aware. It may have to do with the patient's work of breathing. Maybe someone hasn't been tipped off about that, but stating the obvious of what you're seeing is something to incorporate. When something doesn't make sense, gather perspectives on what might be happening. When there is conflict, the bottom line is to decide what is the very best course to take for the patient.

Assessment

When we talk about assessment, we should be somewhat detailed in our assessment. We'll cover the things that we generally discuss and evaluate when we respond as Rapid Response Team. It is very important to know what's normal for the patient. What is their baseline?

Patient History

When gathering a patient’s medical history always find out what medications they're on and what allergies they have. We can get that information from direct care staff reports or the patient's electronic medical record. Get subjective data from the patient and their family when you can. The patient and family need to be listened to. Research shows that when you engage with family and caregivers, better health outcomes occur. The patient’s experience is better and their satisfaction improves. Often the costs are lower because if you're communicating with the patient and family, that's going to help them stay on the road to recovery. It will also help them with their knowledge and understanding of what's happening with their loved ones.

General Appearance

When you hit the door, look at the general appearance of the patient. Observe these things as you take a quick glance and in just a few moments, you can determine the affect of the patient. You can observe the dress, grooming, and personal hygiene of the individual. Posture, facial expression, manner, and attention span can tell you a lot. As you begin to interact, you can also evaluate speech and judgment. You can really tell a lot about what's going on with the patient, especially if you do know them and what they were like previously.

Skin

When looking at the skin, you’ll look at a number of different things. Check for turgor by doing the pinch test where you pinch the skin between your thumb and your forefinger. Sometimes that can indicate dehydration when the skin does not return to normal after one to two seconds. The pinch test might be more effective with the elderly population than younger patients. Dehydration and fluid loss are some of the conditions that you can identify with the pinch test.

Check the color and temperature of the skin, ensuring you always use the back of your hand to test the temperature of the skin. Check for moisture and any kind of manifestations on the skin such as rashes, lesions, wounds, and ecchymosis. Check to see if the skin is warm and dry, pale, or appears to be modeled. Is the patient diaphoretic? Cardiac problems and infections can cause diaphoresis among other conditions.

Head, Ears, Eyes, Nose, and Throat (HEENT)

Looking at the head, ears, eyes, nose, and throat can give us a detailed overall picture of the patient. In a rapid response situation, we may not look at nasal drainage or things of that nature, but we definitely will ask the patient if there has been a change in their headache or if it is a new headache. Look for signs and symptoms of infection or increased swelling in the incision area. Ask if they have congestion in their nasal passages. Listen for complaints of pain in the throat and notice changes in voice quality.

When checking the eyes, check and make sure the pupils are equal, round, reactive to light, and accommodate (PERRLA). Normal pupils range from constricted at about two millimeters to fully dilated at about eight millimeters. As you check for accommodation by bringing the finger closer to the patient, you will notice that the eyes will constrict. Also look for visual-perceptual changes, conjunctiva, sclerae, and nystagmus.

Neck

When you look at the neck, make sure to check the trach site. If the patient has an ET tube or an NT tube, look at that as well. Check patency and make sure that the trach site is supple. Also, look for cervical adenopathy and swollen areas in the neck and lymph nodes. Check for carotid bruits. This might be done by the nurse if it is a cardiac patient. Also look for jugular distension, which can mean fluid overload.

Vital Signs

Gather data as you look at typical vitals. This includes heart rate, blood pressure, respiratory rate, and SpO2. While end-tidal CO2 is not typically measured as a standard vital sign, it can be helpful to check. Not all facilities have or use the technology to evaluate ventilation with portable devices such as a nasal cannula. I believe end-tidal CO2 is something that is underutilized, especially in the post-acute setting. We also need to check the patient’s temperature, pain level, weight, and urine output.

Reasons for Increased Heart Rate

What are some reasons for increased heart rate? This can be caused by hypoxia, fever, any kind of fight or flight response, sympathetic stimulation, or pain. In addition, anxiety, exercise, metabolism, and certain medications can also cause increased heart rate.

Cardiac

For carotid or a cardiac evaluation, the nurses are going to look at and observe the carotids and jugular veins. They are going to look at the rate and the rhythm if we've got an EKG or some kind of monitor to evaluate murmurs. When nurses listen for murmurs, they're listening for systolic, diastolic, and continuous murmurs. Murmurs are caused by defective valves, holes in the heart, fever, and anemia. Pulses in the extremities will need to be checked including the ulnar pulse, the radial, the posterior tibial, and the dorsalis pedis, depending on the areas of concern.

Check the color of the extremities and look for mottling of the skin. As I mentioned earlier, it could have a red and purple-ish look to the skin and be kind of blotchy. Causes include poor circulation and lack of oxygenated blood. Some medications like amantadine and minocycline can cause mottling of the skin as do conditions like hypothyroidism and lupus. Also, look for swelling and edema.

Chest Pain

One of the programs I was involved in and started at our facility was a cardiac rehab program in post-acute. That was during the time of the Go Red for Women Campaign. An important part of our education for the staff, patients, and their families was how to recognize chest pain characteristics and how they differ between men and women. Chest pain can be due to angina, gastric reflux, pleurisy, panic anxiety, or muscle or bone injury. When we have chest pain, we don't always immediately think that it's cardiac. We want to think that there are other conditions that might be causing that chest pain.

For men, generally, it is characterized by a squeezing chest pressure or pain, jaw, neck or back pain, nausea or vomiting, and shortness of breath. For women it's different. They do have some of the characteristics that men describe such as nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, and even chest pain, but there is not always chest pain. Women oftentimes describe their pain as pressure in their lower chest or upper abdomen. Some women have fainting spells, indigestion, or extreme fatigue as descriptors of their chest pain.

Pulmonary

Let's get into our wheelhouse of pulmonary assessments. Some of this is going to be a review for you, but I always feel like when we talk about breathing rhythms it’s helpful to have a little bit of a review. Look at the respiratory rate, rhythm, and the work of breathing. Auscultation should be done posteriorly when able. Listen to lung sounds and identify what lung sounds we hear and what could be going on in that particular area. The lungs may sound normal or there may be crackles (rales), wheezes, rubs, or absent sounds.

There are a variety of respiratory patterns or rhythms. Kussmaul breathing is when you have an increased rate and depth which can happen in metabolic acidosis. Cheyne Stokes breathing is when you have an increased frequency with increasing depth followed by a decrease in depth with a 10 to 30-second period of apnea. That happens when there is low cardiac output. Sometimes near death, you will see Cheyne Stokes breathing, but a low cardiac output due to congestive heart failure can also be a cause. Biot’s rapid breathing is rapid deep inspiration with 10 to 30-second apneic periods.

Reasons for Increased Respiratory Rate

Hypoxia is one reason for increased respiratory rate. In patients with COVID-19, silent hypoxia has been noted with normal lung mechanics, especially in the early stages. Hypoxia occurs with no change in the respiratory rate or depth, so that is all normal. It's suggested that hypoxemia in COVID-19 is a result of the V/Q mismatch when microvascular thrombosis represents dead space with a reduced or absent pulmonary capillary flow that doesn't affect ventilation. The V/Q mismatch may occur with no effect on our breathing.

Other reasons for increased respiratory rate include metabolic acidosis, diabetic ketoacidosis, and sympathetic nervous stimulation, including anything that is that fight or flight response. Exercise, pain, asthma or COPD exacerbations, certain drugs, and fever can also cause an increased respiratory rate.

Six Cardinal Indications of Respiratory Disorder

The six cardinal indications of respiratory disorder are cough, sputum production, dyspnea, wheezing, hemoptysis, and chest pain. When these things manifest, we are going to dig a little deeper. Is there a change in sputum, such as color, consistency, amount, or odor? Do we need to get a sputum sample? Are our patients all of a sudden irritable and restless? Are they particularly drowsy or confused? They could be tachycardic if hypoxic. Remember that chronic steroid use masks fever and elevates white blood cell counts. Cyanosis is a late sign when we're looking at respiratory complications of our patients.

Oxygenation

Factors that affect pulse oximetry include:

- Sensor placement

- Motion/pressure

- Low perfusion (BP)

- Weak or rapid pulse

- Peripheral vasoconstriction

- O2 shunting

- Ambient light

- Nail polish pigmentation

- Carboxyhemoglobin (COHb)

- Jaundice

- Intravascular dyes

A few things to note. Even ambient light shining on the sensor can affect the reading. In my experience, red nail polishes are the culprit to affecting the readings on a pulse oximeter. Carboxyhemoglobin occurs when carbon monoxide binds with hemoglobin, which can give you an erroneous reading. In post-acute, we don't really see carboxyhemoglobin, jaundice patients, or intervascular dyes give us problems. Those things happen mostly in acute care.

Ventilation

When assessing ventilation, we’re again going to look at end-tidal CO2 which is an indication of ventilation and measures carbon dioxide present in the airway at the end of exhalation. Capnometry is when you see numerical CO2 measurements, but do not have a waveform. Factors that can affect capnometry include water vapor, nitrous oxide, and high concentrations of oxygen. This also includes water droplets, secretions, and aerosol treatments in the breathing circuits. The sampling lines will get contaminated which will increase the flow resistance in the tubing and affect the accuracy of the CO2 measurement.

We do a lot of ventilator weaning at our facility and we tried the continuous inline capnography, but we had such trouble with that. We began doing spot checks using a portable CO2 monitor to get that information. Also, during high-frequency low tidal volume ventilation errors occur mainly because of two reasons: exhalation may not be complete, combined with the lagging time of the monitor to recognize the true value.

When there are gradual changes in end-tidal CO2 and we're doing continuous monitoring, something physiologic has happened with the patient. When there is a rapid change, whether it is a spike or decrease in the reading, it is usually a result of equipment malfunction. In the case of resuscitation with a spike in the end-tidal CO2, that is an indication of a good return of spontaneous circulation.

Rate of Perceived Dyspnea

PTs and OTs often figure the rate of perceived dyspnea when working with patients. They also use a scale of the rate of perceived exertion scale as seen in Figure 1. While there is more than one rate of perceived dyspnea scale, Figure 1 shows the Borg scale.

Figure 1. Rate of perceived exertion scale.

I am discussing rate of perceived dyspnea today because I would argue that this tool could find a home in respiratory assessment, perhaps in ventilator or trach weaning. This is especially helpful in post-acute care when you have patients that are on ventilators, have trachs, trach caps, have their speaking valves on, and are having to do their exercises. The PTs and OTs are always asking patients how they perceive their dyspnea and what is the difficulty. If we would incorporate that into our trach and ventilator weaning, it might be a good thing.

What's really important is to educate and re-educate the patient at each interface with them. Ask them, what is your rate of perceived dyspnea today? Yesterday you said that it was around this number and that is an indication that you have a very slight difficulty in breathing.

Palpation and Percussion

Palpation and percussion are generally performed by a medical provider. Palpation is a tactile exam to identify tenderness, asymmetry, diaphragmatic excursion, crepitus, and vocal fremitus. To do palpation to determine diaphragmatic excursion, place one hand posteriorly on each hemithorax near the level of the diaphragm, generally along the spine. Palms should be facing out with thumbs touching at the midline and your hands around the lower hemithorax. Each hand will rotate away equally from the midline when the patient breathes in. Any unequal movement or a minute amount of movement indicates asymmetry and poor diaphragmatic excursion. Crepitus in the lungs refers to crackles under your fingertips and feels like you're squishing Rice Krispies. That's an indication of subcutaneous air with emphysema and pneumothorax.

To test vocal fremitus, place the ulnar (outside) edge of the hand on the chest wall. Have the patient repeat a specific phrase like 99 or one, two, three. The strength of the vibrations felt indicates the attenuations of sounds that are transmitted through the lung tissues. Increased vibration or fremitus indicates tissue density, pneumonia, or possibly a malignancy. Decreased perceived fremitus is when there is more air in the spaces. This could be in overlying fatty tissue, such as in COPD, or fluid outside of the lung space.

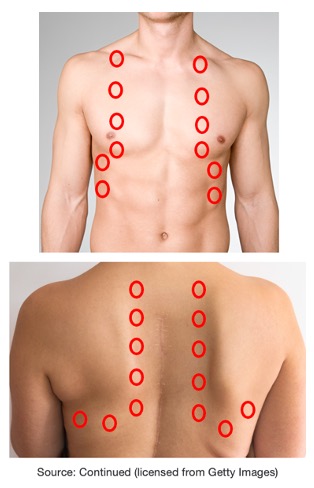

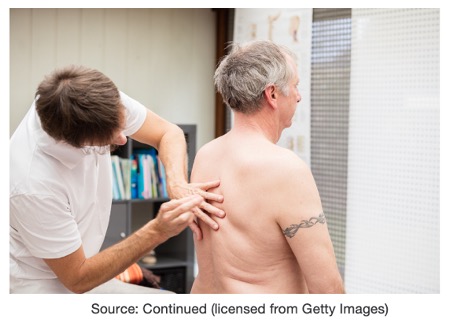

Percussion is done similarly to when we listen to breath sounds. Percuss from side to side and top to bottom and omit the scapula area, as seen in Figure 2. Compare one side to the other, just like we do with breath sounds. In this case, look for asymmetry in the resonance of the sound. Note the location and quality of the sounds you do hear. This helps find the level of diaphragmatic dullness on both sides.

Figure 2. Diagram of where to perform percussion on a patient.

As you can see in Figure 3, the clinician has all of his fingers on the chest to do percussion. I have seen different resources that have explained that the best way to do percussion is to hyperextend the middle finger of one hand and place the distal inter-phalangeal joint firmly against the patient's chest. With the end (not the pad) of the opposite middle finger, use a quick flick of the wrist to strike the first finger. You're not going to be able to do this if you have long fingernails.

Figure 3. Clinician performing percussion on a patient.

Remember it’s a tap, tap, tap with a really quick flick of the wrist. Place the middle finger on the chest, and then the fingers just on the opposite side, just to ground on the chest, not pushing into the chest.

What does percussion sound like in different situations? If you have a non-musical sound that indicates healthy lungs or bronchitis. Hyper-resonance is slightly musical. This indicates too much air, often seen with emphysema or pneumothorax. If it's dull and muffled, you're likely over an organ or abnormal density, which could be due to pleural effusion or lobar pneumonia. If the sound is somewhat flat, that could be because you are over muscle mass or bone. Percussion and palpation definitely take practice and experience. If the opportunity comes up to observe a physician or someone doing percussion and palpation, take it and ask if you can participate.

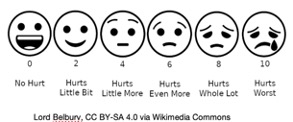

Pain

It's important to assess pain, which can be acute and chronic. Find out the location of the pain and the severity. For some patients that can't communicate very well, a pain scale with the faces can be very helpful in assessing pain, as seen in Figure 4. The descriptions and characteristics of pain can vary and can be very telling as to what type of pain it is. Examples include sharp, dull, achy, stabbing, throbbing, pressure, radiating, prickling, etc.

Figure 4. Pain scale example.

If we're able to get this information, it’s helpful to know what have been relieving factors for a person's pain in the past. We also want to find out what are precipitating or exacerbating factors and what causes their pain to be more, such as movement or breathing. The pain scale is helpful for non-verbal indicators. Either they can identify the faces or you can observe your patient and their facial expression and their body language as to what their pain level might be. We also want to know when the last pain med was given.

Musculoskeletal

There are a number of musculoskeletal factors we will evaluate. One of these is pain, which for a while was considered the fifth vital sign. There is some controversy surrounding this and some hospitals are evaluating it, but are not including it as a fifth vital sign. Regarding pain, find out if this is a new musculoskeletal pain or if it is chronic pain. Determine where the pain is occurring and the quality of the pain. Just as we discussed previously, what are relieving factors and exacerbating factors. Gait, posture, and range of motion may not be evaluated in a rapid response. Other important things to identify include numbness and tingling.

There are different types of pain. Nociceptive pain comes from tissue injury. Visceral pain comes from injuries or damage to organs. A lot of times visceral pain is described as pressure, aching, squeezing, or cramping. Gallstones, appendicitis, or irritable bowel syndrome can also manifest these types of symptoms. Somatic pain results from the stimulation of skin, muscles, joints, or bones. Oftentimes those characteristics are described as constant aching or a gnawing sensation that can be deep or superficial. Neuropathic pain is from dysfunction in the nervous system. Characteristics include burning, freezing, numbness, shooting, or stabbing pain. Diabetes, infections, shingles, or carpal tunnel are other types of neuropathic pain and may have characteristics like I just described.

Genitourinary

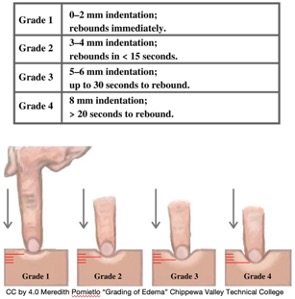

Genitourinary is something we are always on top of, including urine output, concentration, odor, pain, and edema. Figure 5 is the edema scale that shows plus one through plus four of pitting edema. This is assessed when you push into the body and release your finger. The length of time it takes the skin to rebound determines the grade based on Figure 5.

Figure 5. Scale for grading of edema.

Neurological

The brain controls so many things. Components to check include loss of consciousness (LOC), cognition, orientation, sensation, reflexes, strength, speech, and swallow. Many of these components of a neurological exam are addressed in other areas of the evaluation such as strength and reflexes under musculoskeletal.

Our post-acute documentation tool wasn't put into the medical record at first. It included the reasons why you called (the criteria), all of the basic history, vital signs, and a neuro checklist. Many of the items on this PACE team tool were checkboxes where you could simply make a check and spend a minimal amount of time on documentation. It had a place for labs, pre-labs, and post labs.

Also included in the neuro checklist were behavior changes. Observe to see what is different with the patient. Remember, you are looking for new changes in behavior. Are they alert and oriented? Are they confused or cooperative, or are they not cooperating? Are they agitated? Are they unable to swallow? Do they have unclear speech? Are they not responsive or lethargic? Are they comatose? If the answer to any of these questions is yes, to what degree are the changes?

The basic neuro checklist usually includes the Glasgow Coma Scale where you look at and evaluate the eyes, verbal skills, and motor skills of the patient. When you look at the eyes, observe if they are opening spontaneously or just on verbal command. To assess verbal skills, ask questions such as what is your name? what is the date today? and do you know where you are? To evaluate motor skills, assess the movement of the extremities and include any pain that they have with movement.

A score of three on the Glasgow Coma Scale indicates a deep comatose patient or possibly brain death. A fully awake patient will have a score of 15 on the scale. A score of eight or less is sometimes an indication that intubation is necessary, but not always. In emergency rooms, for example, non-invasive ventilation may be used if the physician feels like they're going to be able to get through this without an advanced airway, that it is only going to take some time. It could be a patient who overdosed on a drug and the physician anticipates that they will recover.

Psychological

One of the biggest things that impact psychological conditions is sleep. Sleep abnormalities are robustly observed in every major disorder of the brain, both neurological disorders, such as epilepsy, and psychiatric. Sleep disruption merits recognition as a key relevant factor in these disorders. As you know, whether your patient is in ICU or elsewhere throughout the hospital, sleep is something they can easily be deprived of. Lack of sleep can affect their personality and affect. It can also cause them to have delirium, anxiety, and depression. Get a good night's sleep and help your patients try to have a good night of sleep.

Gastrointestinal

The nurse or physician usually does this quick observation and inspection of the gastrointestinal system. First, inspect the contour and look for any asymmetry of the abdomen. Always auscultate the bowel sounds in the four quadrants before you do any type of percussion. Palpation and percussion of the liver and spleen might be done by the physician. After percussion of the liver and spleen, palpation would be done on the liver edge, spleen tip, kidneys, and aorta.

If there is bloating and distention, the gastrointestinal system can have a negative effect on our patients’ ability to breathe. If they're on mechanical ventilators, it can cause constant high-pressure alarms. To assess rebound tenderness, we use Blumberg’s sign. That is when you apply pressure on an area of the abdomen and then release your hand quickly to see if there is any pain. If there is no pain, then most of the time peritonitis can be ruled out. Other symptoms can accompany rebound tenderness, such as constipation, bloating, nausea, or vomiting.

Other things to look at under GI on our PACE team tool were if the patient was experiencing nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation, or distention. If they are constipated, their abdomen may be distended. According to the CDC, Clostridium Difficile, or C-Diff, affects nearly half a million Americans, and many of them die within 30 days of diagnosis. C-Diff is transmitted through fecal matter, usually orally. The dominant risk is antibiotic use as it affects the microbiome in the gut, killing the good bacteria and the bad bacteria that are causing you difficulty in your gut. When it kills the good bacteria, it diminishes the proliferation of the good bacteria in your gut, making you more susceptible and lowering your immune response.

Don't Forget!

Don't forget to check IV lines, tubes, drains, and medications. Chest tubes can be very positional and displacement can result in tube failure and replacement. If a tube fails to drain, it would need to be replaced and could cause an infection around the wound or empyema. Generally, a thoracic CT is the best way to assess for the placement of a chest tube.

Diagnostics: When and Why

We might do labs if we suspect sepsis or urinary tract infection. These might include UA, blood cultures, CBC, BMP, BNP, CMP, CRP, ABGs, lactate level, and INR. Most labs generally have a very quick return. Some do point-of-care testing. We can do point of care testing at my facility for blood gases and lactate levels. When doing blood cultures, it typically takes just one day for a gram stain result. It often takes two days to identify particular organisms that the patient may be growing and three days to report any anti-microbial susceptibility. Other diagnostics that may be done include EKGs and X-rays.

Collaboration

Collaboration is key, including meeting with your team after wrapping up your assessment. As you meet, look at what you’ve done so far and what interventions were immediately implemented. This could include giving breathing treatments, switching oxygen to high flow, giving diuretic pain meds, giving oxygen, or doing an ECG.

What are the results of these interventions? Consider the history and the findings that you have so far. It can really help response teams to have standing orders. A lot of facilities have standing orders for EKGs for chest pain. We pretty much have free rein to apply oxygen and keep oxygen saturations greater than 90%. We have some flexibility there, but we may need a breathing treatment and sometimes there are standing orders related to giving breathing treatments for wheezing or something of that nature.

When do you call the physician or the nurse practitioner? I taught our team in post-acute to err on the side of caution. We may not even have a physician in the building when you need them. Call them if you need new orders or more extensive assessment is needed. Call for a transfer request if you think that patient needs to be transferred to a higher level of care or back to acute care. Also, call a physician or nurse practitioner if a consulting provider requested it.

Reporting Findings - SBAR (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendations)

When reporting the findings, SBAR is really important. I always say, if you're going to talk to a doctor and try to get orders changed, you better have a leg to stand on. This is really helpful to organize the data that you have and to support that leg to stand on.

- Situation - What is going on and how is the patient presenting?

- Background - What are the factors or the history that just led up to the call? Not the way back history, but just the most recent history that likely impacted this event.

- Assessment - What is going on based on your fact-finding? Summarize what you have done so far.

- Recommendations - What are you asking for? What do you think is best for the patient? What do you want to happen next? Sometimes, our nurse will say, what would you like to do? But I always say the more data that you have and sharing what you think is good for the patient is best. Maybe we just need to increase their breathing treatments or switch their oxygen. This is where it's good to express what you're thinking. Some doctors are going to be more receptive to that than others.

Determining a Medical Emergency

How do I determine if it's a medical emergency? When in doubt, ask the treating provider. However, things like bleeding that won't stop, coughing up blood, sudden dizziness, weakness, and vision changes, especially from a post-acute standpoint, are definitely medical emergencies. Other medical emergencies include a significant change in status in other areas of assessment and if the patient requires services that aren't offered at the current facility. Sometimes we don't have all the things that we need to assess and treat or have all levels of care available.

Rapid Response Teams in Acute Care

Benefits

The outcomes and studies show an inconsistency between facilities and what outcomes they measure and how they measure them. Also, we really don't have data on the long-term outcomes of patients that receive rapid response interventions.

The benefits to Rapid Response Teams in acute care include a decrease in mortalities, code blues, returns to the ICU, and costs. These are general benefits that you see across the board. It depends on the facilities, how supportive they are of Rapid Response Teams, how they gather their data, and what data they actually are getting.

The other thing that we do know about Rapid Response Teams is that the more the Rapid Response Team is called, the outcomes improve linearly in all hospital mortalities, especially in the case of surgical patients. We know that calling the RRT more often causes a decrease in negative outcomes. Another benefit to acute care is increased retention due to the education and mentoring of staff. I believe that any hospital that wants to retain its staff should provide education and mentoring, especially if they have a Rapid Response Team.

Hospital staff satisfaction and patient/family satisfaction are increased when there is a Rapid Response Team. This is because they know that they have that team in their pocket and they will have their back when their patients begin to deteriorate. The satisfaction of patients and families is often related to whether they feel like they have had compassionate communication from the caregivers at the institution. Also important is how patient information was shared with them and what the pain management response was for the patient or their family.

Challenges

One challenge in acute care is keeping the response team at the forefront of staff's minds because people get wrapped up in their day-to-day happenings. If they don't have any rapid response calls for a while, they just kind of forget about it. They're just dealing with the situation, trying to get through the day. Help keep the response team in the forefront of their minds by sending periodic email blasts, through staff reports, or other types of communication such as posters.

Another challenge is a lack of awareness of the system, criteria, and protocols. Having those criteria and protocols easily available to staff and reminding them of these protocols is something that is a challenge because of turnover and those types of things.

Culture and resistance in stepping outside of established norms and silos can also be a challenge in acute care. This is a big thing and is where you really need to dive into what your culture is. In post-acute care, it's so different than acute care. We'll talk about that in a minute. Every hospital says this is how we've done things in the past. They are hesitant to go outside of those types of norms, whether they're the norms of protocols or processes and those things change. Studies show that when calls decrease, more deaths, codes, and transfers to the ICU occur.

Overcoming the custom of only working independently and not asking for help is another challenge. Many of us are proud and feel like we can handle anything and have a tendency not to ask for help. Sometimes it can be the fear of being seen as inadequate or intimidated by more experienced clinicians that come to respond to the call. For example, an ICU nurse that comes down to the general floor may not have the best bedside manner or collaborative skills to make that nurse feel so they may want to resist even calling the team.

Rapid Response Teams in Post-Acute Care

Benefits

One benefit of rapid response teams in post-acute care is that it decreases the number of patients returned to acute care and interrupted stays. Interrupted stays are very traumatic for patients and families, especially when they've come from acute care and are in post-acute where they feel like they're on the road to recovery. All of a sudden, they have to go back to square one which can set them back and set them up not to be able to return to their previous life activities.

Another benefit is the opportunity to establish the best plan of care or next steps. That's what our PACE team is able to do. We have time to look at the patient as a multidisciplinary team as they are early in their deterioration and establish the best plan. In addition, these designated teams provide care providers with a thorough assessment and evaluation of the patient by completing the head-to-toe assessment and using the SBAR.

The education and mentoring of new nurses and RTs are also beneficial. Not everyone naturally takes the opportunity for teaching moments. Ongoing education is very helpful, especially when you use mock scenarios. We had mock code training at our facility. We had pediatric and adult mock code training, and we were beginning to incorporate scenarios of subtle deterioration into our training. We always had such good results and feedback from our staff about having those case studies to review and to participate in.

Cost savings to the facility is also a benefit to post-acute rapid response. Anytime we can keep patients on the road to recovery without setbacks it is going to be cost-effective as well as providing higher quality care.

Challenges

The challenges in post-acute care are similar to those in acute care. One of those is keeping the response team at the forefront of staff's minds. To help with this, I created table tents in the report rooms that said things like is your patient experiencing any of these criteria today? The list of criteria was listed below the question. On the flip side, it listed information about the team and included the male and female characteristics of chest pain.

Like in acute care, there is a lack of awareness of the system, criteria, and protocols. To help with this we had small quick reference cards that could fit in your pocket listing the signs and symptoms of the male and the female cardiac, as well as the criteria for calling. We also regularly shared case studies and our data at staff meetings. This gave us the opportunity to remind them and update any changes that we might've had. For example, we started having the nurse and the RT as the ones that could call the PACE team, but then we ended up incorporating the PTs, OTs, and speech therapists. This change was because I had multiple calls that came to me because the nurse wouldn't call the PACE team. They would say, this is what's happening. I think the PACE team needs to be called. Then I would go down and intervene with the nurse and collaborate with her about calling the PACE team. We ended up including PT, OT, and speech in the individuals that could call.

The culture and resistance in stepping outside of established norms or silos are another challenge acute and post-acute both