Introduction

Thanks so much for that introduction. I am thrilled to be here to talk about dysphagia in post-extubated clients. It takes a team, as we will see as we go through our discussion today. Let's start by reviewing some information about respiration.

Respiration

Rate

- Respiratory Rate

- Adults: 15-16 bpm

- Older Adults: 20’s

- >35 = impending respiratory failure

- And…

- >25-30 = deterioration in the coordination of breathing/swallowing is likely

Typically, the resting respiratory rate for an adult is somewhere between 15 and 16 breaths per minute. This number bumps up a bit as people get a little bit older. If the respiratory rate gets up into the thirties, this is a client with impending respiratory failure. You may not know that once that respiratory rate is elevated to somewhere between 25 and 30 breaths per minute, there is also going to be some deterioration in breathing-swallow coordination. This can potentially result in dysphagia and aspiration. There is a very close relationship between the respiratory rate and the potential for swallow dysfunction.

Work of Breathing

- Physiologic: the force required to overcome elastic and frictional resistance

- Expansion of lungs against recoil

- Airway resistance

Besides respiratory rate, we also have to consider the work of breathing. The work of breathing is defined as the energy required to move air through some fairly narrow airways and expand the lungs against the natural recoil of the rib cage and the musculature.

Breathing and Swallowing

- Larynx primary and original function was breathing; higher and more anterior

- Laryngeal descent allowed for oral communication, but…

- Need for airway protection

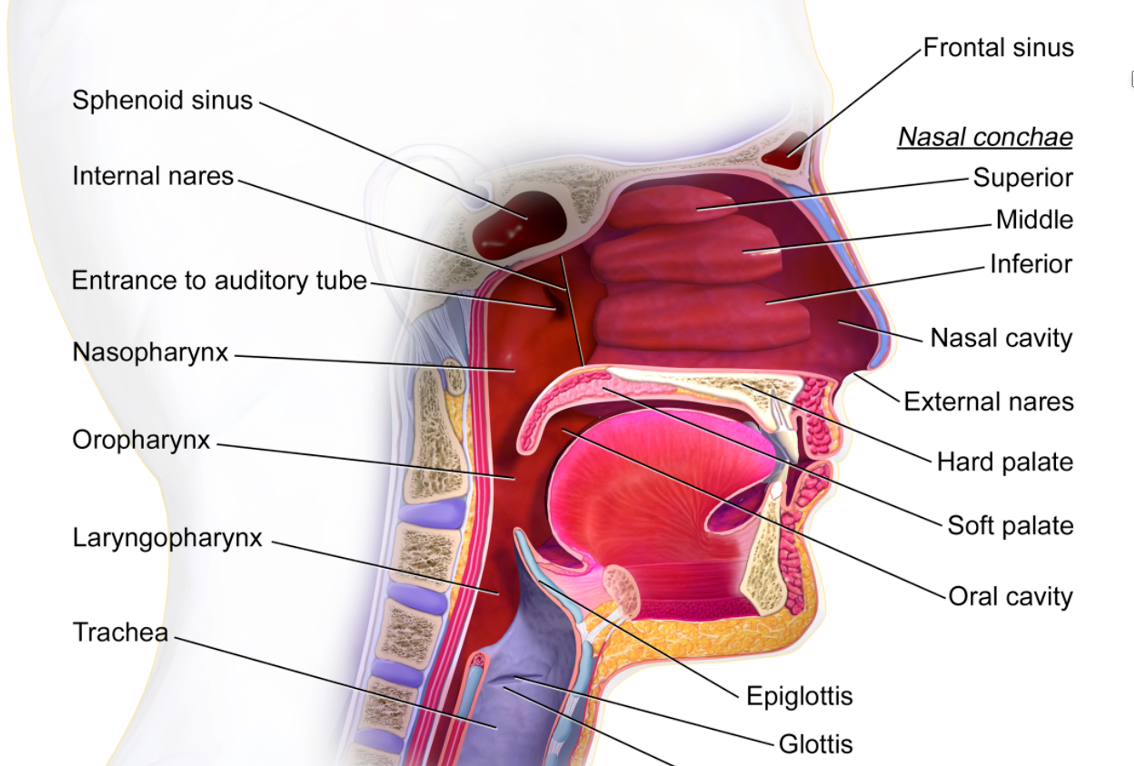

Let's now bring swallowing into the picture to look at the coordination between breathing and swallowing. The anatomical design, as noted in Figure 1, does not make a lot of sense.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the nasal and mouth cavities.

We have a system where food and liquid have to go past where we breathe. This is maybe not the best design. If you look from an evolutionary perspective, however, it makes a little more sense. In early human beings, the larynx and the surrounding structures were in a higher, more protected position and tucked under a more rounded tongue base. Over time, we saw those structures separate and descend. This increased our access to the larynx for voice and led to the development of communication. Consequently, this positioned the airway in a more dangerous position in terms of airway protection related to eating and drinking. Some redundancies in terms of airway protection developed as a result. It is a very well-protected airway as there are many things we can do during swallowing specifically designed to protect the airway. These include all of the things that we do to keep the food and liquid moving. These movements include the initial push on the bolus with the tongue, the movement of the epiglottitis that deflects the bolus away from the airway, and the squeeze of the pharyngeal muscles that keep that bolus moving through the pharynx into the esophagus. These maneuvers close the airway itself with laryngeal elevation, higher laryngeal excursion, closure of the laryngeal valve, and abduction of the vocal folds. These things protect the airway, but one of the most important things that we do to protect our airway is to stop breathing.

Breathing and Swallowing Do Not Occur Simultaneously

- Swallow Apnea

- Begins before bolus enters hypopharynx

- It ends with the bolus tail entering the esophagus

- Changes with the bolus:

- As bolus increases in volume…

- Duration increases

- Earlier onset

- As bolus increases in volume…

- Changes with patient populations:

- As we age…

- Longer duration

- No change in onset

- As we age…

- With disabilities…

- Increased duration in ALS, CP

- Decreased duration in COPD, BPD

(Palmer and Hiemmae, 2003)

We do not breathe and swallow simultaneously. Depending on the term you prefer, this period of respiratory pause or swallow apnea is critical to airway protection. Like most aspects of the swallow response, it is variable. Typically, that period of respiratory pause begins before the food, and the liquid enters the hypopharynx and then ends as the tail of the bullous is entering the esophagus.

Again, there is a lot of variability in terms of onset and duration. Surprisingly, some of that variability is related to the bolus itself. Larger boluses mean longer periods of respiratory pause. This is not a surprise. We also see variability in different patient populations. As people age, for example, we tend to see longer periods of respiratory pause regardless of bolus size.

We also see some important differences in disabilities. We have to ask ourselves what the underlying cause of the swallowing impairment is. In patients with neuromuscular diseases like ALS or children and adults with CP, we tend to see longer periods of respiratory pause. They can stop breathing to swallow and then have trouble getting back to breathing. Reinitiation of respiration after the swallow is sometimes delayed. Patients whose underlying issues are respiratory-related, like COPD or children and adolescents with bronchopulmonary dysplasia tend to have shorter than typical periods of respiratory pause. They are not breathing very well to start with, so they do not have a good tolerance for that period of respiratory pause associated with swallowing. They need to return to breathing more quickly. Thus, we tend to see shorter periods of respiratory pause in these populations.

Breathing-Swallowing Coordination

- “Exhale-Swallow-Exhale”

- The Post-Swallow Exhalation…

- Facilitates airway clearance

- Facilitates laryngeal closure (vocal folds are partially adducted)

- Facilitates laryngeal elevation (the diaphragm is returning to a relaxed state, reducing traction effect)

- Facilitates esophageal clearance

There is a normal breathing-swallow coordination pattern: inhale, exhale a little, swallow, and exhale some more. The swallow typically interrupts the exhalation, usually early in the exhalatory part of the process. While there can be variability, most swallows in people follow an exhale, swallow, exhale pattern.

Post-swallow exhalation is the critical part of the process. That post-swallow exhale has a lot of different functions. One, it helps to facilitate airway clearance. If you have some residue near your airway post-swallow, if you inhaled, you would aspirate. But, if you consistently exhale post-swallow, this keeps out residue in the airway. The post-swallow exhalation also helps to facilitate laryngeal valve closure because the vocal folds are partially adducted, and it helps to facilitate laryngeal elevation, and therefore laryngeal closure. Upon exhale, the diaphragm returns to a relaxed state. During relaxation, the diaphragm is not pulling on the larynx in the same way as it does during inhalation. The larynx can now elevate and, therefore, close.

There are also some pressure relationships that we need to think about. When you inhale, your lungs expand and put some pressure on the esophagus. As you exhale, that pressure comes off of the esophagus, and the material that you have swallowed is now freer to move through the esophagus into the stomach. Thus, you get better esophageal clearance with that post-swallow exhalation as well. As I said, there are many different functions that post-swallow exhalation serves.

Breathing and Swallowing Pressure Relationships

Figure 2. Breath and swallowing pressure relationships.

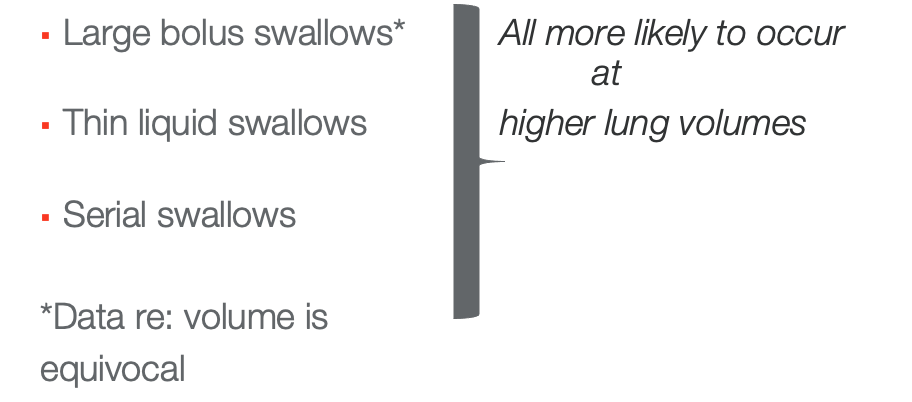

We also know that part of breathing-swallow coordination is related to lung volume. More challenging swallows (larger boluses, thin liquids, or fast moving serial) will require higher lung volumes. Your brainstem knows that these swallows will be tricky and want to make sure there is enough air. I am not suggesting that every time you take a sip of water that you fill your lungs to capacity to get through it. Obviously, we do not do that. There is a mid-range of lung volume where most swallows occur, while these more challenging swallows occur at the higher part of the mid-range. This is going to have implications for patients who cannot expand their lungs very well.

Lung Volumes

- Why?

- More oxygen reserve available for O2 saturation?

- Enhanced expiratory pressure to reduce aspiration risk?

- And….

- Swallows at lower lung volumes (end-expiration) more likely to result in aspiration

- May contribute to breathing-swallow discoordination – decreased fb from pulmonary stretch and/or subglottic pressure receptors to the resp CPG

How do we explain this relationship between swallowing and lung volumes? It seems to be related to oxygen reserve. We need oxygen reserve to get us through this period of respiratory pause. For those of us with normal swallow and lung function, this is barely noticeable. We do not feel any respiratory exertion associated with our swallowing. However, think about people who have an impairment in one or both systems. It will take that additional energy and additional oxygen reserve to get through that period of respiratory pause for them. Swallows that occur at lower lung volumes and near end exhalation are more likely to result in aspiration. This is probably what is happening with a lot of our patients with underlying pulmonary disease.

This is certainly what happens with you and me when we aspirate. Often, when people with normal swallow and respiratory function aspirate, it is because our coordination was off. For example, we might be laughing or talking while eating or drinking. We inhale when we should have been exhaling, or we tried to swallow near the end of the exhalation when our coordination was off.

We also know that these swallows are at lower lung volumes near the end expiration. Another contributing factor to breathing-swallow discoordination is feedback from the pulmonary stretch receptors or the subglottic pressure receptors. In other words, this is something that is happening within the brain stem in the respiratory central pattern generator. This is fairly theoretical at this point, but it is one of the proposed mechanisms for this discoordination that we see in some of our patient populations.

Respiratory-Swallow Coordination

- So...Exhalation – Swallow – Exhalation

- But:

- As we age…Post-swallow inhalation is more common

- Also more likely with respiratory compromise

Exhale, swallow, exhale is a common pattern. We do know that post-swallow inhalation occurs in those of us with healthy systems. If you come in on a hot day and grab your water bottle take a long swallow, which gives you a prolonged period of respiratory pause. You will then be air hungry and need a post-swallow inhalation. We know that post-swallow inhalation starts to happen more commonly as we age. The respiratory system becomes a little less elastic and efficient. Again, post-swallow inhalation is much more common in patients with underlying respiratory compromise. That period of respiratory pause associated with the swallow becomes difficult to manage. They get air hungry and then need a post-swallow inhalation.

- Respiratory-Swallow Patterning (exhale-swallow-exhale)

- Lung Volume Initiation (low-middle to middle lung ranges or 42-55% of vital capacity)

- Respiratory Pause Duration (0.5 to 1.5 seconds)

(Curtis and Troche, 2019)

When we use the term respiratory-swallow coordination, we are essentially talking about three things. We are talking about the respiratory swallow patterning, which ideally is exhale, swallow, exhale. We are talking about lung volume. And again, we need folks to be near the middle part of the lung range. And finally, we are talking about the duration of the respiratory pause, which should be somewhere between a half-second and a second and a half. All three of these components come together to allow us to coordinate breathing and swallowing safely.

- Impairments in respiratory-swallow coordination associated with dysphagia

- Increased pharyngeal transit times

- Pharyngeal residue

- Penetration/aspiration

- Delays in swallow initiation

(Troche et al., 2011; Gross et al., 2003; Morton et al., 2002; Nilsson et al., 1997; Yagi et al., 2017)

We also know that when breathing and swallowing coordination are impaired, people have dysphagia. They have problems with pharyngeal transit, pharyngeal residue and cannot clear their pharynx. They are more likely to aspirate and have delays in the initiation of the swallow.

Post-extubation Dysphagia

- Post-extubation dysphagia is not uncommon

- Prevalence varies…

- 56% of patients undergoing endoscopic swallow evals within 48 hours of extubation aspirated (Ajemian et al., 2001)

- 86% of patients undergoing VFSS post-extubation demonstrated aspiration (Partik et al., 2000)

- Review - 3-93% (Brodsky et al., 2020)

- Meta-analysis revealed a dysphagia rate of 41% (McIntyre et al., 2020)

Respiratory swallow discoordination is an important cause of dysphagia and one of the contributing factors for post-extubation dysphagia. We know that when individuals have been intubated for a period of time for respiratory support and then are extubated, it is likely that they have some degree of swallow dysfunction.

Prevalence is all over the place, as you can see. Post-extubation dysphagia was 56% in one study and 86% in another. In a review by Dr. Brodsky, the prevalence was anywhere from 3 to 93%. When you see numbers like that, it does indicate a high-risk population that we need to have on our radar.

Why the Variability?

- Type of assessment used (screening, clinical exam, Fluoroscopy, Endoscopy)

- Timing of assessment

- And…

- Variability in patients themselves

Why is there all of this variability in the research? One reason is that there is not a lot of consistency in how dysphasia is assessed. In some of the studies, a clinical assessment was used, while in others, it was via a water screening. In some other studies, they did an instrumental assessment using either endoscopy or fluoroscopy. The other factor that varied was when the assessment was completed. Was it assessed immediately after the extubation? In some studies, it was not assessed until 24 hours after the extubation. In others, the assessment was completed several days after the extubation.

Think about your patients in the ICU. They are far from a heterogeneous group of folks. These are patients who perhaps have lung disease, have had strokes, or some other neurological dysfunction. These might even be COVID patients. There is a high degree of variability in the patients themselves, which is probably another contributing factor and why we cannot really get a good handle on the actual incidents of post-extubation dysphagia.

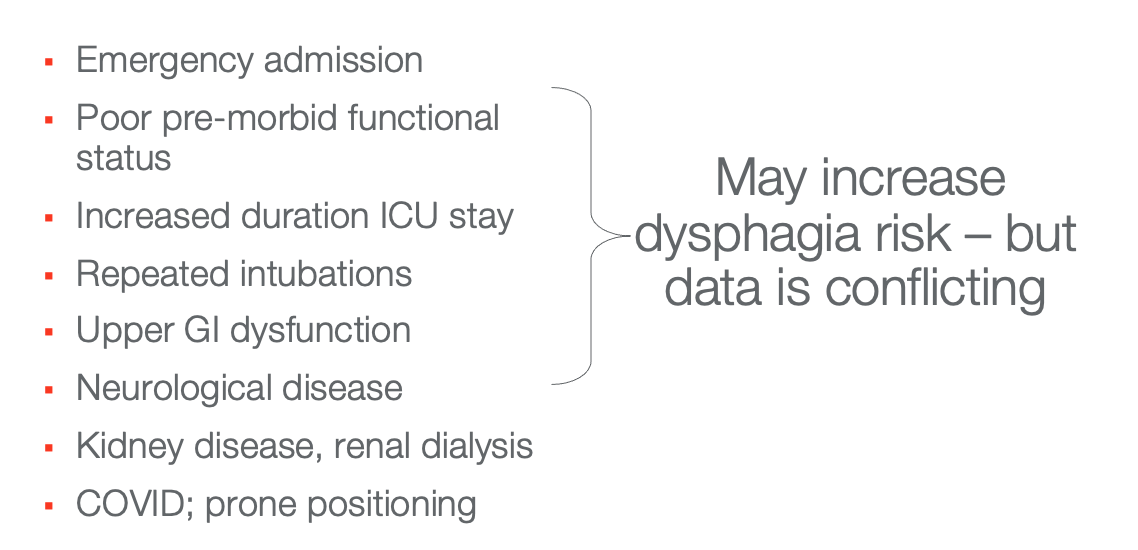

Who is at Risk?

Figure 3. List of those at risk for post-intubation dysphagia.

We do have some information about risk factors, as noted above. There is some conflicting data, but these are things to keep on our radar. Folks who were admitted emergently, and more importantly, intubated emergently will be at higher risk. Clients who were not doing so well to start with or impairments pre-morbidly are at a higher risk (kidney disease, renal dialysis, etc.). Clients at risk are also those who have underlying neurological diseases, long ICU stays, long periods of intubation, repeated intubations, or complex medical conditions are at high risk. COVID seems to be a risk factor for post-extubation dysphagia, as does prone positioning, which we see used very commonly in the management of COVID. Prone positioning seems to create more damage to the airway that folks are then having to deal with once they are extubated.

Does Age Matter?

- Maybe yes…in cardiac and trauma patients

- Maybe not…in surgical, neurological populations

(Brodsky et al., 2020)

What about age? Is that an important risk factor? Maybe. Again, it seems to depend on the underlying diagnosis. It seems to be a factor for cardiac and trauma patients. Older patients also seem more likely to have post-extubation dysphagia. In surgical and neurological patients, there was no clear relationship between age and the likelihood of dysphasia.

Does Duration Matter?

- Yes!

- Durations <12 hours result in reduced risk

- Risk increases significantly after 48 hours and continues to increase as intubation becomes more prolonged (Skoretz et al., 2014; Kwok et al., 2013)

One important consideration is the duration of intubation. This does seem to be a fairly consistent risk factor across studies. When patients are intubated for less than 12 hours, there seems to be agreement amongst the research that the risk of dysphasia will be low in those folks. The risk increases dramatically after 48 hours of intubation, and it seems to continue to increase as the duration of the intubation is extended. The more prolonged the period of intubation, the more likely we will see some post-extubation dysphagia, and the more severe that post-extubation dysphagia is likely to be.

Why Dysphagia?

Usually More Than One Issue…

- Underlying illness

- Medication

- Laryngeal trauma

- Impaired sensation

- Breathing-swallow discoordination

- Reflux

- Cognition?

- Something else???

Why are we concerned about dysphagia? Why do people who have been intubated and are now extubated experience swallow dysfunction? There seem to be many things going on in each particular patient. It is usually some combination of the underlying illness that got them to the point where they needed intubation in the first place, medications, laryngeal trauma associated with intubation, impaired sensation related to the duration of the intubation, breathing-swallow discoordination related to the underlying lung disease. Reflux seems to be a factor in some of these patients as well. Perhaps changes in cognition might be part of the issue. These are complex folks with lots of things going on.

Why Is The Patient In ICU In The First Place?

- Trauma

- Neurological event

- Respiratory disease

- Medication effects

- ICU acquired weakness

There may be some factors that we have not really identified yet. The first thing we have to ask is why are they in the ICU in the first place? Are they in the ICU due to trauma, neurological events, or respiratory disease? Those things could cause dysphagia all on their own, aside from the complications associated with the intubation. We also want to think about medication effects, particularly sedating medications that can depress the respiratory and swallowing systems. Prolonged periods of intubation and ICU stays can cause disuse atrophy and debilitation. In fact, ICU-acquired weakness is probably a contributing factor to swallowing impairment as well. You have probably heard the term, "Use it or lose it." This is one of the things that happens when folks are intubated for long periods of time. If the swallow response is not activated, the swallow response becomes reduced. Again, this is related to the duration of intubation. In addition to atrophy of the swallowing system, we see weakness in the diaphragm and respiratory muscles and generalized fatigue and weakness associated with the ICU stay.

Laryngeal Trauma Associated With the Intubation

- Mucosal irritation, injury

- Dislocations of cartilage

- Edema, erythema

- Granulation tissue

- Subglottic*, glottic stenosis

- Vocal fold paralysis

*Subglottic injuries/pathologies may be under-estimated as most assessment is indirect visualization (Stocker, 2018)

Another important factor for dysphagia post-extubation is laryngeal trauma associated with intubation. There can be irritation or injury to the mucosa around the airway. Sometimes, there can even be a dislocation of cartilage, swelling, and the development of granulation tissue in some cases. This can cause subglottic and glottic stenosis. Some subglottic pathologies may be underestimated as it is not often assessed. We also know that there is a risk of vocal fold paralysis resulting from intubation trauma.

- Laryngeal Trauma results in:

- Dysphonia, hoarseness

- Throat pain

- Stridor

- Dyspnea

- And of course…

- Dysphagia

(Stocker, 2018; Ambika et al, 2019; Brodsky et al, 2018)

Clinical outcomes associated with laryngeal trauma include voice changes, hoarseness, dysphonia, throat pain, strider, dyspnea, and of course, a swallowing dysfunction as well. Another contributing factor is likely related to changes in airway sensitivity.

Alteration in Airway Sensitivity

- Assessed laryngeal sensation (via laryngeal adductor reflex) post-extubation and correlation to aspiration

- When the duration of intubation was short (<100 hours), impaired laryngeal sensation was predictive of aspiration

- When the duration of intubation was long (>100 hours), impaired laryngeal sensation was not predictive

- Impact of overall medical complexity?

(Borders et al., 2019)

This study from a couple of years ago assessed laryngeal sensation. They used a burst of air to trigger the laryngeal adaptor reflux in patients recently extubated. They correlated an impaired laryngeal sensation to aspiration. In the group of patients for whom the duration of the intubation was short, less than 100 hours, impaired laryngeal sensation was directly predictive of aspiration likelihood. However, in patients who had longer periods of intubation, greater than 100 hours, the impaired laryngeal sensation was no longer predictive. In folks with more than 100 hours of intubation, I think things just get way more complicated. Now, you have clients with longer periods of disuse atrophy, are more likely to be more medically complicated, have more weakness, and have longer periods with sedating meds on board. The picture becomes more complicated, and there is not that direct relationship to laryngeal sensation anymore.

- Alteration in laryngeal sensation may be caused by:

- Presence, size of the ET tube

- Neurological impairment

- Sedating medications

- Altered level of consciousness

What causes the change in laryngeal sensation? Some factors could be the presence and size of the ET tube. However, some of the research around size is inconclusive. Again, this is a heterogeneous group of folks. Some of them have a neurological impairment which could be contributing to a decrease in laryngeal sensation. And many have had sedating medications on board. This is also likely to be a contributing factor. These folks may not really awake and alert immediately post-extubation and demonstrate decreased laryngeal responsiveness.

Breathing/Swallow Discoordination

- Post-swallow inhalation?

- Reduced tolerance for respiratory pause?

- Shorter than typical respiratory pause?

Another important potential cause of dysphagia in this population is the breathing-swallow discoordination issue. We just talked about what that coordination looks like in respiratory patterning, the duration of swallow apnea, and lung volume initiation. If you think about recently extubated patients, it makes sense that they would have some issues in all of those areas. They will not have a good tolerance for that period of respiratory pause associated with swallowing, and frequently, we see a post-swallow inhalation. Many have difficulty getting to the middle part of that long range, so there will be some issues there. We are more likely to see that post-swallow inhalation is associated with shorter than typical periods of respiratory pause. Whenever there is an underlying respiratory compromise, we will see these changes in terms of breathing-swallow coordination, as we have established.

Gastrointestinal Functioning/The Role of Reflux

- Increased work of breathing delays gastric emptying

- Crural muscles of the diaphragm are critical to the competence of LES - increased ventilatory effort overcomes pressure in LES (Avazi, S., et al., 2011)

- Resulting reflux may result in laryngeal injury; may be aspirated

- Pre-existing upper GI comorbidity predicted prolonged dysphagia post-extubation (Brodsky et al., 2017)

Another causative factor that we need to think about is gastrointestinal functioning, specifically with the role of reflux. When people are working harder to breathe, the energy goes to breathing. The energy has to come from somewhere. At any moment in time, we have a finite amount of energy available to us. When the work of breathing increases and energy goes to breathing, one of the places energy gets pulled from is the gut. As a result, we see slower gastric emptying and slower digestion as work of breathing increases. Unfortunately, when digestion slows, reflux increases. The longer that food and liquid stay in your stomach, the more likely you will reflux it. It is a vicious circle. The work of breathing increases because of the underlying respiratory compromise, the energy goes to breathing, digestion slows, and reflux increases.

There is also a potential for aspiration of that reflux which further exacerbates the work of breathing. The diaphragm, specifically the core muscles of the diaphragm, are important in maintaining lower esophageal sphincter function. When folks work harder to breathe, that increase in ventilatory effort tends to overcome the pressure in the lower esophageal sphincter, and reflux is more likely. For those reasons, we are more likely to see reflux in these patients. And if the reflux is high enough and enters the pharynx, it has the potential to be aspirated and to create further laryngeal injury, laryngeal edema, and irritation. There is an obvious relationship then between gut functioning and swallow and aspiration management.

Cognition

- The relationship between swallowing and cognition is unclear, but…

- Impaired cognition results in…

- Decreased vigilance, self-monitoring

- Inability to utilize compensations

- Reduced participation in rehabilitation

Another important consideration here is the patient's cognition. It is unclear exactly what the relationship is between swallowing and cognition. We know that patients who have impaired cognition will have more difficulty self-monitoring, less vigilance, and more difficulty using voluntary compensatory strategies. They are also not going to have the same level of participation in rehab. This is not really a one-to-one direct relationship between impaired cognition and impaired swallow function after extubation. Still, we can think about impaired cognition as being perhaps more of an extubatory factor.

Strategies

ABCDEF Bundles, aka ICU Liberation

- ABC – Awakening and Breathing Coordination

- D – Delirium Interventions

- E – Early Exercise and Mobility

- F – Family Education and Support

One of the strategies that is commonly used in ICUs is the ABCDEF bundles. In your facility, you may use that term or a more general term called ICU liberation bundles. The idea is to put some programming in place to decrease these prolonged ICU stays and prolonged intubation periods. The ABC stands for awakening and breathing coordination, D is delirium interventions, E is early exercise and mobility, and F is family education and support. Physicians, nurses, respiratory therapists, speech pathologists, and physical and occupational therapists all work together to decrease the impact of these prolonged periods of decreased mobility, prolonged periods of intubation, and prolonged periods of sedation. The studies that have looked at these bundles have documented that they have good outcomes.

- Results in…

- Fewer re-intubations

- Lower mortality

- Fewer ICU re-admissions

- Fewer patients diagnosed with delirium

(Mart et al., 2019; Pun et al., 2019

With this, we can reduce the risk of re-intubation, lower mortality rates, decrease readmissions to the ICU once folks are transferred to a lower level of care, and decrease delirium, which is certainly an important outcome.

Impact on PED?

- No studies where PED was an outcome

- But…

- Improved alertness, cognition is likely to have a positive impact on swallow function

Do these bundles have an impact on the frequency or severity of dysphasia post-extubation? We do not know as there were not any studies where post-extubation dysphagia was an outcome. Unfortunately, nobody has looked at that directly. We know that when patients are more alert and have better cognition, they are more likely to do better in swallowing function. They will be able to utilize strategies more effectively and participate in exercises and activities designed to improve their mobility and swallowing. Intuitively, we can say that these bundles probably have an impact on post-extubation dysphagia likelihood and severity.

Non-invasive Positive Pressure Ventilation

- May prevent the need for intubation, re-intubation

- But, is there an impact on swallowing?

- Not a well-studied relationship

- Removal of mask intermittently for fluid/food intake is often part of protocols

- Consider RR, effort, baseline 0-2 saturation

Commonly, non-invasive positive pressure ventilation is used in facilities. It is an important tool in terms of managing these folks in respiratory distress. They are very well-documented as being able to prevent the need for intubation/re-intubation. What we do not know is the potential impact on swallowing. At this point, it is not a very well-studied relationship. Often, protocols are in place to remove the BiPAP mask or the CPAP mask intermittently so that folks can have sips of water or have something to eat. In some individuals, this seems perfectly appropriate, while other times, it might not be. The problem is we do not have a lot of research yet to help guide us. In the absence of research specific to these interventions and these patient populations, I think we have to think about respiratory functioning in general related to swallow function.

We need to look specifically at the breathing-swallow coordination, the respiratory rate, the work of breathing, and oxygen saturation levels of these individuals. We have to treat these patients like any other potentially compromised patient.

What About High Flow Oxygen?

- It can also prevent extubation failure (Zhu et al., 2019)

- Heated, humidified air and oxygen at high flow rates

- Increased patient comfort (absence of mask provision of humidification)

- CPAP effect decreases atelectasis

- Decreases WOB

What about a high-flow nasal cannula? This is also an important intervention. It can help to prevent extubation failure and the need for re-intubation. It allows for the presentation of oxygen at much higher flow rates in a much more comfortable manner. And, it helps to manage atelectasis to decrease the work of breathing. It has really nice respiratory outcomes. What we do not know is its impact on swallow function and breath and swallow coordination. There is very little research to look at at this point. It is a fairly high-pressure intervention. Those pressures may put people at higher risk for aspiration as it could blow secretions into the airway.

- But What About Swallowing?

- Pressure in the pharynx may increase aspiration by “blowing” secretions, etc. into the airway; may dampen cough strength (Flores et al., 2019)

- As LPM increases, so does pharyngeal pressure (Parke and McGuinness, 2013), but…impact on swallow has not been studied

- This resulted in oral swallow changes (Eng et al., 2019) and longer durations of LVC (Allen and Galek, 2020)

There is some evidence to suggest that those pressures may dampen cough strength as well. This would not be a good outcome in terms of swallowing. We know that as flow increases, pharyngeal pressure also increases. Does this have an increasing impact on swallow function? We simply do not know. When they put a high-flow nasal cannula on folks with normal swallow function, they found some oral changes in terms of oral bolus manipulation and longer durations of laryngeal valve closure. Thus, folks with the normal swallow function had to modify what they were doing in the face of these higher pressures. They had to modify how they managed the bolus orally, and there was a change in terms of that period of swallow apnea. In a more compromised population, what is the impact? I think we need to tread very carefully in this area.

The Long-Term Picture for ARDS and Endotracheal Intubation

- Patients with ARDS and oral endotracheal intubation post-discharge from ICU

- Follow up at 3, 6, 12, 24, 36, 48, 60 months post d/c

- At the time of discharge from the hospital, 32% had dysphagia

- 23% reported symptoms persisting more than 6 months

- Duration of ICU stay (not the duration of intubation) predicted delayed recovery

- All dysphagia resolved within 5 years

(Brodsky et al., 2017)

These are some of Dr. Brodsky's work that I find very interesting. It is the only study that I am aware of that looked at patients post-intubation for a long period of time. They followed them throughout their ICU stay and then followed up at discharge from the ICU at three months, six months, 12 months, and 24 months and so on. You can see that they looked at these clients at intervals up to 60 months post-discharge.

At the time of discharge from the hospital, about a third of them still had some degree of dysphasia, and about a quarter of them reported symptoms that persisted for more than six months. Interestingly, the predictive factor for the delayed recovery of swallow function was not the duration of intubation but rather it was the duration of ICU stay. This is probably a measure of medical complexity and a degree of disuse atrophy rather than the intubation itself. This is not to say that intubation is not problematic, but the predictive factor in long-term disability for swallowing was the longer ICU stays. That was an interesting outcome. As I said, they followed these folks for up to 60 months post-discharge. All of the dysphasia had resolved itself by that point. There is clearly a progression that the longer post-extubation, the more things start to improve.

Oral Feeding

- Should we wait to initiate oral feeding?

- Delaying evaluation 24 hours may allow for less restricted diets (Marvin, et al., 2018)

- Or not…

- The majority of subjects passed swallow screen at 1-hour post-extubation (Leder et al., 2019)

When should we think about oral feeding and medications by mouth? Unfortunately, the research is conflicting. We have one study that says delaying swallow evaluation, and therefore, the initiation of oral feeding should be 24 hours as this resulted in less restricted diets and better swallow outcomes. However, Dr. Leder's study showed that most patients in their cohort passed the swallow screen at an hour post-extubation. And again, I think it just does not make sense to try to make sweeping generalizations about this population as there is too much variability in terms of underlying medical conditions and things that got them to the ICU in the first place. We also need to look at the duration of the intubation, and the ICU stay. These are all important variables that are all over the place in terms of their impact.

How Do We Identify Patients With PED

- Screening

- Clinical assessment

- Instrumental assessment

Given all of that variability, how do we go about identifying those patients with post-extubation dysphagia? We are going to review screening, clinical assessment, and instrumental assessment next.

Swallow Screening

- Variability in screening protocols, policies

- A survey in 2012 revealed that 41% of facilities had a screening protocol in place for patients post-extubation

- Screening administered by RNs (66%), SLP’s (27%), or a combination (3%)

(Macht et al., 2012)

One of the things that we can all be involved with is a swallow screening. This will help us to identify those patients who then need more complete clinical assessments and perhaps instrumental evaluation of swallow as well. Swallow screening is a sort of a yes/no question or a pass-fail procedure. If you pass, you move on to an oral diet, and if you fail, you are referred for a further swallow assessment. There is a lot of variability in terms of policies and protocols within facilities. And they might have different policies for different areas of the hospital. From facility to facility, you might have different types of screening protocols in use. They are not yet universally utilized in this population of patients who are post-extubation.

The study by Macht and colleagues goes back to 2012. However, it is the most recent one that surveyed facilities about their procedures for patients post-extubation. Less than half of them had screening protocols in place. I hope that this is a higher percentage now, but unfortunately, nobody has looked at it again.

Nurses, speech pathologists, or some combination often do this screening. I can tell you that in my facility, the swallowing screening is done universally. Depending on where patients are in the hospital, it might be the ED physician who does the screen, a nurse, or the speech pathologist. In our ICU for post-extubation patients, that screening is primarily done by nursing.

- These tools did include patients with PED in their sample:

- Bedside Swallowing Evaluation

- Yale Swallow Protocol

- Post-extubation Dysphagia Screening

There are lots of different screening tools. Some of them included patients with post-extubation and had the potential for post-extubation dysphagia, and some did not. These are the three (Bedside Swallowing Evaluation, the Yale Swallow Protocol, and the Post-extubation Dysphagia Screening) validated to include patients who had been recently extubated.

Bedside Swallowing Evaluation

- Administration of graded food/liquid textures (tsp ice chips, tsp nectar, tsp puree; 5ml thin; ½ cracker)

- SLP observes for clinical signs of aspiration: cough, throat clear, change in vocal quality, wet breath sounds, stridor

- Followed by a 3 oz water test for comparison

- Low specificity and sensitivity overall

(Lynch et al., 2017)

The bedside swallow evaluation is a screening tool that involves administering several different food and textures in an integrated manner. You start with ice chips and then move to thickened liquids, purees, liquids, and solids. It is designed to be administered by a speech pathologist who observes for clinical signs of aspiration. A 3 oz water test follows it. The 3 oz water test is a commonly used screening tool. It is a larger volume of water, three ounces, and the patient is instructed to drink that water without stopping to take a breath. This is a challenge for them. However, this does not have very good specificity and sensitivity, unfortunately.

Yale Swallow Screen

- Orientation; following directions

- Oral mechanism exam (lingual, labial ROM; facial symmetry)

- 3 oz. water test

- Validated for use by RNs, SLPs

- Validated with patients with a variety of etiologies

(Leder et al., 2014)

This is the Yale Swallow Screen. This is probably a swallow screening tool that has the most research to support it. It has the best validation. It has been used for a wide variety of patient populations, including patients who were recently extubated. It involves a quick cognitive screen that involves orientation and an ability to follow directions. It also involves a quick examination of the oral mechanism looking at lingual and labial impairments in terms of the range of motion, facial symmetry, and then a 3 oz water test. This tool is specifically designed to be used by speech pathologists and nurses. As I said, this has been validated with a wide variety of patient populations, including patients with post-extubation dysphagia.

Post-extubation Screening Tool

- Assessment of level of alertness, respiratory status, s/s dysphagia, or medical complexity (full protocol is in the article)

- No boluses administered

- “Fail” triggers SLP evaluation

- Sensitivity 81%; Specificity 69%

(Johnson et al., 2018)

Th Post-extubation Screening Tool was designed specifically for patients who have recently been extubated. This involves assessing the level of alertness, respiratory status, and any clinical signs of dysphagia. It does not involve any food or liquid. The clinician looks through the client's medical record and observes the patient for risk factors. If those risk factors exist, the patient is considered to have failed, and they are referred for a full swallow evaluation. This is something that any member of the team can administer. It has fairly good sensitivity but not so good specificity.

Review of Water Swallow Tests

- Compared water screens with smaller(single sips) and larger boluses (3 oz)

- Larger volumes (with serial swallowing) better at ruling out aspiration

- Smaller volumes better at ruling in aspiration

- Combining vocal quality assessment with a water test increases the accuracy of the water test

(Brodsky et al., 2016)

Recently, Dr. Brodsky and colleagues reviewed all of the screening tools that involved water swallows. As an aside, if a person aspirates water, that will produce the least amount of damage to the lungs. Thus, if we are not sure what your swallow function looks like, water will be the safest thing. Most screening tools involve some sort of water administration. He compared all of the water swallow tests that were out there with varying water boluses. The larger boluses were using the 3 oz water test. The swallowing test without stopping was better at ruling out aspiration, but smaller volumes were better at ruling in aspiration. So, a good screening tool includes smaller sips and larger boluses.

Clinical Assessment

- A recent review of clinical approaches:

- Given the variability in screening protocols in ICUs, variability in access to instrumental assessment, and lack of evidence re: clinical assessment protocol…

- Recommend:

- Swallow screen followed by clinical assessment, augmented by instrumental assessment whenever possible

(Perren et al., 2019)

Perrin et al. (2019) found that given all the variability in screening protocols in ICUs, they recommend that a swallow screen is followed by a clinical assessment and then augmented by instrumental assessment whenever possible.

Let's define some terms. A swallow screening is a yes/no procedure. It might involve water sips or simply a review of the medical record. A clinical assessment is the observation of the client's eating and drinking and might incorporate some strategies. It does not allow us to visualize the pharynx. We can look at breathing-swallow coordination and potential discoordination, but it does not allow us to identify whether aspiration is occurring definitively. This is why they recommend that these clinical assessments be augmented by instrumental assessments like a modified barium swallow study or an endoscopic swallow study. These allow us to visualize the pharynx to see if aspiration is occurring or not.

The problem is that we are talking about patients who are recently extubated, who are really ill, who do not have much mobility, and who are fairly fragile. Moving them from the ICU for swallow study is potentially problematic. Often, we rely on our screening plus our ongoing clinical assessment until folks are a little more stable. There are no established protocols for assessing swallow function or breathing-swallow coordination that have been validated specifically to this population of patients with post-extubation dysphagia.

Watch the Breathing!

- Respiratory Rate

- At rest

- Change with demands of swallowing?

- Depth

- Shallow?

- Pain with breathing?

- Coordination

- Changes across bolus types, size

- Single swallows vs. serial swallows

- Changes with fatigue?

Let's look at what we do know about the relationship between breathing and swallowing. One of the things we know is that it is important to pay attention to is breathing. When we ask people to eat or drink, we want to pay attention to their breathing. We want to see how the respiratory system responds to the demands that swallowing is placing on the system. Remember, swallowing requires breathing cessation. So it puts demands on the respiratory system. How is this respiratory system responding to those demands? This means watching the respiratory rate. What is that at rest, and then what happens when you start your swallow trials? We want to pay close attention to that and an increase in respiratory rate. And as a speech pathologist, I rely very heavily on input from the respiratory therapists in terms of the variability in the respiratory rate in this individual. If that is too high, that may be telling me that I have to decrease the demand on the system.

We also want to look at the depth of respiration. We need some assurance that this individual is getting at least to the middle part of the lung range. A person with a lot of respiratory muscle/trunk weakness that cannot maintain an upright position will have difficulty expanding their lungs and getting to the middle part of the lung range.

We want to watch that breathing-swallow coordination, particularly paying attention to that post-swallow pattern. Am I starting to see a post-swallow inhalation? This tells me this is someone who is not tolerating that period of respiratory pause very well. And if I see it, when does it happen? Am I seeing it all the time? Do I see it only at the end of the meal when they are getting tired? Do I see it at the end of the day when they are more fatigued? Do I see it with different oxygen settings? If they get more oxygen and increased flow rate through the nasal cannula, they may sometimes do better from a swallow perspective. Again, respiratory therapy and speech pathology need to be work together to look for those patterns.

Respiratory Factors Associated With Aspiration

- Rapid RR (>25 bpm)

- Low baseline oxygen saturation (<94%)

- Inconsistent swallow-respiratory pattern

- Post-swallow inhalation

- Short swallow apnea duration

(Steele et al., 2014)

This was a review of all of the research looking at respiratory factors associated with aspiration across patient populations. What are the respiratory factors that should be red flags for us? One is a respiratory rate higher than 25 breaths per minute. Another is low baseline oxygen saturation levels. A patient who starts at 94% or lower has nowhere to go when you start to impose breath holding during swallowing demands. In fact, many clinicians get concerned about drops in oxygen saturation during swallow trials.

The research has been all over the place in that regard. Several studies looked at that. Some studies documented that drops in oxygen saturation were associated with aspiration events; however, these drops in oxygen saturation were not associated with actual aspiration events. Again, we do not really know, and there is probably too much individual variability. What is clear is those patients who start low at 94% or lower have nowhere to go. They have no reserve. Then, as they start breath holding associated with swallowing, they will quickly get into trouble. Thus, the baseline oxygen saturation will be an important area to pay attention to before we give an individual something to eat or drink.

We also want to look for inconsistencies in breathing-swallow patterns, post-swallow inhalation, and shorter than typical periods of respiratory pause. These are well-documented factors in a more generalized patient population with respiratory compromise and not specific to recently extubated patients. However, I think it is reasonable to assume that these would apply.

Dyspnea

- Look for:

- Increased respiratory rate

- Activation of the neck, upper rib cage muscles

- While speaking:

- Inspirations mid-word or phrase

- Decreased syllables/breath

- While swallowing:

- Holding bolus in the oral cavity to take extra breaths

- Pausing between swallows for breath

(Hoit et al., 2011)

We also want to be looking for dyspnea. Dyspnea is one of those umbrella terms that encompasses lots of signs and symptoms of breathing discomfort. In terms of dismay during swallow trials, we are looking for increases in respiratory rate and activation of the accessory muscles that informs us there might be some respiratory muscle weakness.

As a speech pathologist, I pay attention to swallowing, but I also listen to the individual's voice and speech production. These are activities, like swallowing, that are dependent on breath support as well. Sometimes in conversation with the patient, even before we get started with the swallow trials, I can see if a person is getting into trouble. For example, they may not get good volume or stop more frequently to catch their breath while talking. Then, during a swallow, we are looking to see if they need to stop to take breaths more frequently.

One of the other things that we pay particular attention to is a bolus hold. You may see the patient take a sip of water or chew up a little bit of their lunch, and then they need to hold it in their mouth for a few seconds before swallowing. This is often related to an underlying decrease in breathing-swallow coordination. Breathing is always going to win and take priority. Your body is saying, "Nope, you can't swallow right now. You have to keep breathing." This is another big red flag.

Respiratory Muscle Strength

- Maximum expiratory pressures (Via EMST device)

- Pulmonary Function Tests (functional vital capacity, expiratory volumes, peak flow)

- Peak Flow Meter (Silverman, et al., 2014)

- Also…

- Trunk control; positional stability

- Observations re: WOB

We also want to get a sense of respiratory muscle strength function. We can get some data through pulmonary function tests and expository muscle strength training devices. These are devices that are used to exercise those respiratory muscles to improve swallow function and voice production. We can get some baseline data from those devices.

Recently, we have seen in the literature evidence to support the use of peak flow meters during voluntary cough to get some sense of respiratory muscle strength. Certainly, our informal observations are very valid here as well. Look at the patient. What are you seeing? If this is someone working hard to breathe, is it because they have no trunk support or cannot maintain an upright position?

Pulse Oximetry and Aspiration

- Several studies looking for a correlation between changes in pulse oximetry and aspiration - but no reliable correlation found (See Britton et al., 2020 for review)

- Better for measurement of “work of breathing,” endurance for feeding

- But…

- Low baseline numbers may indicate aspiration risk

This the research that I was referring to earlier regarding a relationship between drops in oxygen saturation measured via pulse oximetry and aspiration events. As I said, nothing is conclusive. As I said a moment ago, the baseline level is the more important number to pay attention to. If we are working with a patient and watching that O2 sat level dropping, is the person aspirating? No, I do not know if he is aspirating or not. What I do know is this is not going well. I do not know if this is someone for whom the demands of swallowing are significant, impacting respiratory function. This is another area where I think it is important for respiratory therapy and speech pathology to work closely together. What are the parameters for this particular patient? What should I be looking for? When should I be stopping my swallow trials?

Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR)

- Impaired Cough Predicts Impaired Swallow

- Reductions in Peak Expiratory Flow Rate (PEFR) have been demonstrated to predict aspiration

(Pitts et al., 2008; Pitts et al., 2010; Hegland et al., 2014)

There is increasing evidence to support this relationship between impairment and cough and impaired O2 function. We can measure voluntary cough via peak flow meters. Reductions in peak expiratory flow rate as measured in that way have actually been demonstrated to predict aspiration.

- Measuring Peak Flow

- <200 lpm likely to be ineffective

(Bianchi et al., 2012; Silverman et al., 2014; Sakai et al., 2019)

This may be a tool that we start to see used more commonly in our ICUs, as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Example of a peak flow meter.

This can help us to identify patients who are at risk for aspiration more efficiently and effectively. As previously stated, we cannot always go down to the radiology department for a swallow study. This tool is more portable. We are starting to see more research and norms around what we should be looking for. Right now, anything less than 200 liters per minute looks to be ineffective in terms of a cough response that will protect the airway. This tool may be coming to an ICU near you soon. At my facility, we have been talking about this for a while. However, with COVID, we have not been able to work out the infection control piece yet. We are still hoping to be able to do more consistently in my facility.

Instrumental Assessment

Consider

- Stability of patient for transport out of ICU (for VFSS)

- Agitation

- Level of alertness

There are options for instrumental assessment like fluoroscopic and endoscopic swallow studies that allow us to visualize the airway during swallowing to determine if aspiration is occurring and why it is happening. Again, this is tricky in this population. We cannot always move patients out of the ICU very easily. Patients are not awake and alert for long periods of time, and you may miss your opportunity. Patients can also have delirium and agitation. Doing instrumental assessment is not always feasible, so we are always looking for tools that can be implemented in the ICU itself. Ideally, we want tools that can be used in more of an interdisciplinary way.

Management

- Considerations:

- Level of acuity

- Endurance

- Ability to participate, utilize strategies, compensations

The speech pathologist may not always be there, and patients fluctuate considerably. Team management becomes critical to keep these patients safe. In terms of management, what are some of the things that we want to think about as a team? What is this individual's medical acuity, respiratory function, and swallow function? We want to work together around strategies that can improve endurance and decrease some of that disuse atrophy. We need to come together to assess this patient's ability to participate and utilize strategies and compensations.

- So…

- Work within a team

- Expect fluctuations

- Give it time…

- Tools:

- Diet

- Exercise

- Energy Conservation

As the speech pathologist coming in to do the swallow evaluation for a recently extubated patient, I may be new to the scene. I have not been treating them during their ICU stay. I rely on team members' reports around fluctuations, performance, level of alertness, and where we are in terms of medication management. Have we started to wean them from sedation? I need to work very carefully with nursing and respiratory therapy to have a good picture of what is currently going on. Due to these fluctuations, I do not always have the best sense of how this patient is actually functioning. One of the things that I think is really critical in managing patients post-extubation is to give these folks a little bit of extra time to recover. We saw that in the natural progression of the dysphagia