Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Positive Verbal Strategies for Connecting with Children, presented by Amber Tankersley, PhD.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Identify characteristics of a positive verbal environment.

- Identify characteristics of a negative verbal environment.

- Describe how to implement positive verbal strategies for connecting with children.

The Verbal Environment

Let's start by looking at what the verbal environment entails. Think of all the interactions that you have with the people around you, including the children in your programs, classrooms, or in your home. Everything that you say, even your nonverbal communication, sends a message to children. We want that environment to be very positive. We want children to have great relationships with the people who are there to help care for and educate them. Within the verbal environment, there may be a positive side and there may be a negative side.

Positive Verbal Environment

In a positive verbal environment, children feel those connections. It is a good rewarding experience when they are interacting with other caring adults. Hopefully, the adults are modeling what a positive verbal environment is. It helps maintain and build those positive relationships. We want children to feel cared for, safe and valued. In a positive verbal environment, they will feel all those things.

Negative Verbal Environment

In a negative verbal environment, children do not have good quality verbal interactions with others. Children feel like they do not matter, are unworthy, unlovable, insignificant, or incompetent. We do not want children to have that experience. We want children to have a good feeling about themselves, and we want them to feel comfortable having interactions with other people.

Characteristics of a Negative Verbal Environment

Below are some characteristics of a negative verbal environment. Hopefully, if you are in a situation and you hear something like this or you start seeing a pattern that you are saying negative things, you might be able to stop yourself or share some positive strategies with someone else.

- Shows little/no interest

- Ignores children’s interests

- Pays insincere attention

- Discourages expression of ideas

- Speaks discourteously

- Uses sarcasm

- Asks rhetorical questions

- Uses insincere or destructive praise

- Criticizes children

- Uses words for control

- Uses names of children to mean “NO”…

- Uses judgmental language to describe children

If you are in an environment and the adults do not show any interest in the children, such as a child tugging on your shirt to get your attention and you dismiss them, that is a negative verbal environment. That is not even giving children a chance to communicate with you. If you are ignoring children's interests, that sends a message to the child that what matters to them does not matter to you. That may be their strategy for trying to interact with you and now that has failed. Ignoring children's interests is definitely something to avoid.

We need to perk up our ears and listen to what children are interested in so that we can use their interests to help build a relationship with them. Another characteristic is giving insincere attention. For example, if the only interaction that you have is, "Oh, your shoes are so cute," that is a great thing to say to a child. They are proud of their shoes, but it is not the attention for who they are or what they are doing that is coming from you. We want children to feel good about themselves, not just that their shoes look cute.

If you are not helping children express their ideas through communication or helping them get in touch with their feelings that also creates a negative verbal environment. Hopefully, adults that are working with children are being courteous and respectful. If not, that sets up a negative verbal environment. Sarcasm has no place in an early childhood classroom because children do not understand the meanings behind some of the things that we joke around about with adults. That is not respectful to the children, so avoid any sarcasm.

Another characteristic of a negative verbal environment is not asking questions that we really do not need to know the answer to (rhetorical questions). I joke around that we often are constantly asking children questions such as, "What sound does a dog make? What sound does a cow make?" If we really do not need to know the answers to those questions, why are we asking them? It is just setting children up to think, this person keeps asking me these silly questions that I think they already know the answer to, so I am not going to interact with that adult anymore. Be very careful not to ask questions that are unnecessary.

Using insincere or destructive praise is also very negative. An example is saying, "Your picture is really nice, but you could have used more color or you could have stayed in the lines." Those types of statements are hurtful to a child. It does not put them in much of a mood to continue having an interaction with the adult. If you are always putting a child down or criticizing them, that tends to stop those potential conversations in moments of interactions with children.

If we are using words for control, such as STOP, NO, or a child's name, that does not help the children and they tend to tune those out. I had a child that every time I said his name, which was quite frequently in the very beginning, my children would perk up their ears to see what he had done. They knew that every time I said his name, it was in connection to something that I probably was not happy about. Children pick up on that very quickly.

We want to make sure that we use their names, but do not use their names to mean, stop what you are doing. Using judgmental language to describe children creates a negative verbal environment as well. When we tell children, "You are being lazy,” or, “You are lollygagging,” or, “Quit dawdling, you are so slow catching up to the group" it does not help a child. It makes children hear a label over and over again. The more frequently they hear those labels, the more frequently they believe that is what is true about themselves. We want children to have great self-esteem and feel good about themselves. Avoid using that language that makes children believe things are true about themselves that really are not.

Creating a Positive Verbal Environment

Now the good part, which includes the things that we want to start doing. These are some things that you would see in a positive verbal environment.

- Greet children

- Use children’s names

- Engage in frequent conversation

- Follow children’s lead

- Find ways to begin and maintain conversations

- Provide encouragement to children during conversations

- Be mindful of the pace of interactions

- Use active listening

- Use silence effectively

- Speak politely and respectfully

- Choose your language carefully

- Invite elaboration

Children often do not have an initial positive interaction with an adult. We want to greet children and use their names, which lets them know that you are truly talking to them and that you care about them. Say hello to children and have a system for greeting them. There are a lot of unique greetings that people come up with that are fun. That helps set the tone for the interactions that will follow.

Engage children in frequent conversation. I talk a lot and I talk a lot to children. I ask children questions or try to talk with them to see what is going on in their lives, to see what they think about the weather or about what is happening outside. I try to find key moments that are perfect for engaging children in conversation. There is not a bad time to talk to children. One of my prime times to talk to children in our preschool program is during snack time because it is a relaxed atmosphere. I enjoy talking to them about different things such as what is going on and what they think about the snack.

This is a prime time to facilitate and start building relationships. One of the things on the negative side was ignoring a child's desire to speak with you. On the flip side, follow a child's lead and pick up on the fact that they want to talk or that they want to have an interaction with you. Go with it, answer their questions, and physically follow them if they are trying to show you something. We have to find ways to start the conversation, keep it going, and not miss their clues. For example, if a child comes up to you and says, "Will you come read a book with me? Will you come sit with me?" it may not be just the book they want, they want that connection.

Follow their lead and as children are talking, provide encouragement to keep them talking. Have some prompting questions and include some pauses to invite them to fill in the empty space. We want to give children a chance to practice having conversations. We certainly have to be mindful of the pace of our interactions. I tend to start talking really fast when I am talking to adults, but with children, I tend to slow down. I tend to have more deliberate pauses to help them feel that give and take of a conversation.

I think it is really important for adults to remember to use active listening and silence. Take those moments to pause and really listen to what a child is trying to say to us. Often adults are distracted by so many different things. We have a lot of responsibilities when we are working with children and we are torn in so many different directions that we often do not truly listen to what children have to say. Listen to children, get down on their level, and truly try to understand what they are trying to get across to us.

Speak politely and respectfully. Use concrete language. There are many words that have multiple meanings that could be interpreted differently. One example from a book I used to read to children is flour and flower. This book has some characters that were making a cake for another character's mother. They read a recipe and saw that they needed white flour to make the cake, so they went in search of the perfect white flower. Was it a rose? Was it a tulip? Was it a chrysanthemum? Obviously, that was not the type of flower the recipe called for, but that language was very confusing for children because why would something that was so very different have the same sound. Be very careful that your language is easily understood by children.

When you are interacting with children, invite them to elaborate and tell you more. One of the strategies that we will look at here in a little bit is perfect for inviting children to elaborate and fill in the blanks. That helps keep that conversation going and helps make that great positive verbal environment happen.

Positive Verbal Strategies

Let's dive in to these positive verbal strategies. These are perfect for you to try out with the next child that you are interacting with or even with your coworkers. They will help make a great positive verbal environment for anybody that you are interacting with.

Behavior Reflections

The first strategy is that of behavior reflections, which are nonjudgmental statements made to children regarding some aspect of their behavior or person. This may include:

- Show interest

- Provide narration

- Should be non-threatening

- Assist in receptive language skills

- Help adults begin an interaction.

They are really simple to use. You have probably used them already but did not call them this. This is a simple statement made when you see a child doing something. It is a statement narrating what they are doing. It is nonjudgmental. It is a way to show interest. For example, “I see that you are doing this (stacking blocks, rolling play dough, etc.).” It gives them some language that helps describe what they are doing and it is presented in a way that is nonthreatening.

It is not saying, "Oh, you are doing this and you should not be doing this." It is simply stating what you see a child doing. It helps children be able to hear language and to describe what they are doing. They may not know exactly what to call what they are doing, but when you put that label on it, it helps them think, "Oh, okay. I know what that is now. I have heard that word before and I keep hearing it and it must mean what I am doing." It also helps adults begin an interaction. If you use a behavior reflection, children sometimes may say something back to you and it may begin a conversation.

To formulate a behavior reflection, begin by making a statement to the child about what they are doing. Direct it to the child and then wait and see what happens. It is not necessary to word this as a question because we are not questioning the child's behavior, we are just stating what we see the child doing. Use descriptive nonjudgmental vocabulary as part of the statement.

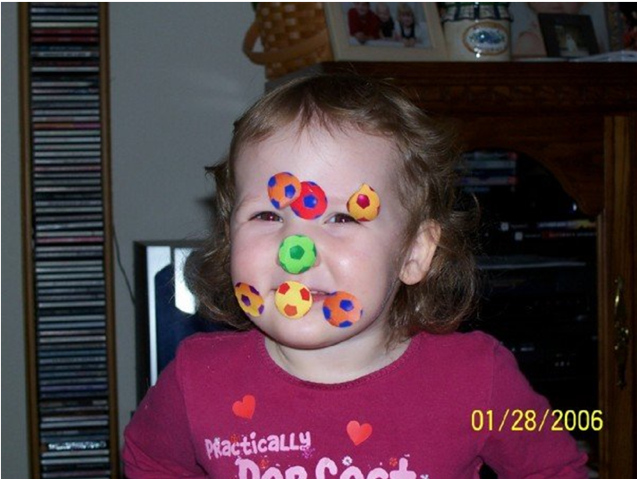

Figure 1. Young girl with stickers on her face.

Let's look at a couple of examples. Figure 1 is actually my daughter, Samantha, with stickers on her face. I remember I was working on something and she popped around the corner and had these stickers on her face. A simple behavior reflection, if you are faced with a child that has done something to themselves is simply, "You have stickers on your face." For some reason, I tend to say, "Oh, you have stickers on your face." I do not know why I always act surprised with my behavior reflections, but that is just a pattern that I fall into. It is simply stating what you see the child doing. It is not, "Get those off your face. Those belong on paper." It is just simply, "You have stickers on your face." Or I could even elaborate and say, "You have soccer ball stickers on your face."

Figure 2. Young girl brushing a goat.

Figure 2 shows Samantha brushing a goat. A simple behavior reflection could be, "You are brushing the goat," or, "I see you are brushing the goat." It does not have to be, "What do you think the goat thinks about you touching them?" It is just simply, "You are brushing the goat. I see you are brushing the goat." That is all you have to do. It is super easy to formulate behavior reflections.

Conversations

The second strategy is conversations. That may not sound like a huge strategy because we have conversations with children and people all the time.

- Show concern or interest

- Help children develop positive relationships

- Help children gain confidence in speaking and listening

- Help enhance children’s social understanding

- Can develop from children’s questions of “Why?” and “How come?”

Conversations help people realize that we are either concerned or we are interested in something that they are doing. Conversations help us maintain those relationships with one another. With children, it certainly helps them gain confidence in having conversations with other people. They have to have practice and they have to have real moments to have conversations. When we have conversations with children, it may help them better understand what is happening around them, whether that is in their social world, their family, or the community.

Something that is so easy to use and sparks conversations with children is to use the questions that they very commonly ask, especially in those early childhood years. It might be why or how come, but even if you do not know the answer, working with them and countering with another question may help children maintain a conversation. You both might find out why or how come something happens, even if you are not really sure to begin with.

Using questioning in conversations. One of the techniques for beginning or maintaining conversations is using questioning. The best type of questions for starting or maintaining conversations is open-ended questions. Open-ended questions require more than a one-word answer. Open-ended questions require more than, "How old are you? Four. Would you like to go outside? No." You want to have the child answer with more than just one simple statement because that does not start a conversation. If you ask a child how old they are and they tell you four, the conversation is over because you have nowhere else to go. The question was asked and I got the answer.

With questioning, we also want to avoid asking too many questions. It is really easy to take a nice conversation with a child and turn it into an interrogation if we are asking too many questions. It should not be like we are playing the game of 20 questions where we ask questions and wait for answers. Use those questions to facilitate a conversation without it being overwhelming for the child.

Also, avoid rhetorical questions that you already know the answer to. Asking a question just to ask a question does not help either one of us out. Make sure that you are asking questions that are truly beneficial to the child. Again, avoid close-ended questions with a one-word answer that does not take the conversation anywhere.

Open-ended questions ask children to:

- Predict

- Reconstruct an experience

- Imagine

- Make comparisons

- Solve problems

- Generalize

- Reason

- Evaluate

- Propose alternatives

- Make decisions

Here are some examples of open-ended questions to ask children.

- Make a prediction.

- What do you think would happen, if we ran out of snacks today?

- Reconstruct an experience that they had.

- Remember when we went to the farm, what are some of the things that we saw? What are some of the things that we did?

- Have them imagine.

- Imagine if you were king of the world, what would you be in charge of? Or what would you do differently?

- Make comparisons.

- Did you like today's snack better or yesterday's snack?

- What do you think would be better to add to the dramatic play center?

- Solve problems with the questioning that you are asking.

- I have used problem-solving as a way to generate conversations with groups of children, such as in a class government situation. With preschool-aged children, you might be sitting at meeting or circle time and have an issue to discuss. It could be that the caps on the markers keep being left off and our markers are drying out. Bring that problem to the children. Our markers are drying out because we are not getting the caps back on. How do we fix that problem? How do we make sure that we get the caps back on the markers? Have them help solve that problem. They are more likely to own it and feel like they have helped solve something real because they have. They are more likely to follow through when they have had a hand in solving that problem. Practice and allow children to solve some problems, even if it is not the quickest way to solve the issue. Not only is great cognitively, but it is also great for their conversation and a good verbal environment.

- Make generalizations.

- Take what they know about a book that they read and generalize the characters in another situation. Use what they know about the visit to the farm to think about what is going to happen when they go to the zoo.

- Apply reasoning.

- My favorite is on a rainy day when you are leaving and all the worms are on the sidewalk, ask the children, "Why do you think all these worms are on the sidewalk? They weren't here earlier and now it has rained and here they are?" Have the children try to think of a reason for that.

- Make evaluations.

- This is great with food items. If we have had something new for a meal, I would ask the children to do an evaluation or critique of the food. We could provide that to our cook to say, "Yeah, we would love to have this again,” or, “Maybe do not fix this one so often."

- Propose alternatives.

- What do you think we should do instead?

- What do you think we could do?

- Make decisions about things.

- What would you like to do about this?

- Make sure it is open-ended.

Practice

Figure 3. Boy holding a stringer of fish.

Next, we are going to practice using questioning for conversation starters. In figure 3, you see a boy who is holding a stringer of fish. If I asked a question such as, "How many fish did you catch today?" he could tell me, "I caught four," and he could walk away because that did not draw him into a conversation. Instead, ask a question such as, "What are you going to do with those fish?" or, "How did you catch them?” or said, “Show me how you caught them. What were the steps that you went through to catch those fish?" That helps prompt a possible conversation and get the child more involved. Show them that you are truly interested in what they are doing and want to know more. It may make this child feel like an expert to show you how he has caught these fish.

Figure 4. Girl digging in the sand at the ocean.

Take a look at the little girl in figure 4. If you asked her, "What are you doing?" and you asked it kind of in an accusatory manner she may not be apt to begin a conversation. But if you ask questions such as, "What do you think you will find if you keep digging in the sand?" or questions about the process of the waves washing away the sand, or what types of things do you think live in the water she is more likely to respond, have a conversation, and think you are more interested in her. Practice using some good open-ended questions to start conversations with children or with somebody that you really do not know very well.

Conversation Stoppers

The next strategy, conversation stoppers, goes along with conversation starters. I think it is important to think about and practice things that stop conversations so you are more likely to not use them. You may ask a question and realize that it stopped the conversation. When I asked my college students to come up with some conversation stoppers, they were so good at supplying them. It makes me wonder if they have had a lot of people that have used techniques talking to them that have stopped conversations.

Once we start practicing them, I am sure you are going to think of so many times where somebody has said something to you where you immediately thought, "I am not talking to you anymore." We do not want children to think like that.

- Missing a child’s conversation clues

- Immediately correcting a child’s grammar

- Supplying unnecessary facts or opinions

- Providing unsolicited advice

- Inappropriate questioning techniques

If you miss a child's chance at talking to you, that is certainly a conversation stopper. If you have a child that says, "Come sit with me, Mrs. T." and you do not, that is definitely a way to stop a conversation with that child.

Another conversation stopper is if you immediately correct a child's grammar or pronunciation of something. If you have a child that says, "Mrs. T I brunj you some flowers," and you say, "No, you did not. You brought them to me." That child is immediately going to think, "Okay, she does not like what I said. She does not like what I have done. I am not going to push this any further." This ends a possible conversation with that child. There is a better way to correct what they say if they say something that is not correct that is a lot more gentle and helpful to them than immediately jumping back with the correction. We will talk about that technique in just a minute.

Supplying unnecessary facts and opinions can stop a conversation. If a child is trying to start a conversation with you and you counter with, "I already know that" or, “Yes, and this is also true about that,” the child will likely not want to continue to talk to you. If you are constantly adding one more thing that seems better than what that child has to say, they are eventually going to think, "Well, what I say, good enough for this person" and they may not continue that conversation with you. Avoid supplying unnecessary banter, back and forth with a child. Sometimes this is hard to do with adults. I am sure you can think of an adult who does this to you.

Providing unsolicited advice can also stop a conversation. If something happens to a child and you respond, "Well, I knew that was going to happen. You should have seen that coming. That is what happens when you do this and that." Providing that unsolicited advice does not help your chances of having a conversation with that child.

Another conversation we have already touched on is inappropriate questioning techniques. This includes a barrage of questions that do not allow a child to even think about what they are answering. They are constantly answering one right after the other, which does not help a child in their attempt to have a conversation with you.

It is time to practice some conversation stoppers. This will help you think twice about actually employing them in your conversations with children and others.

Figure 5. Boy under playground equipment.

The little boy in figure 5 is playing in some mulch under a piece of playground equipment. If I approached him and said, "You need to get out of there. We do not play in the mulch,” or, “Keep the mulch on the ground. Why don’t you go play somewhere else?" I might want to encourage the child to play somewhere else, but if I do not engage him in conversation, it may be a harder attempt to move him or redirect him out of that situation. Instead, I might ask, "What are you looking for? Is there something interesting under the playground equipment? Have you found something in the mulch?"

There are so many possible questions that could have been asked that would start a conversation that we have missed by trying to immediately redirect that child into whatever we think is more appropriate. We want to have that conversation with the child. We want to give them a chance to talk to us and tell us why they are under the equipment. Are they trying to get away from somebody? Ask those good questions that start a conversation, rather than just trying to hurry a child out of a situation.

Figure 6. Boy with spray bottle painting a sheet outside.

Figure 6 shows a little boy who is using a spray bottle to spray paint onto a sheet of paper that we have hooked onto our playground fence. We are certainly not afraid of mess and this is certainly a messy activity. In this situation, there are some great ways to spark a conversation with this child. However, if I said one of the following it is not helpful to the child.

- You are too close to the paper.

- Why did you pick that color?

- You are making a mess.

- You are getting that all over your hands.

- Do not get that on your clothes.

We might encourage a child to try a different technique if what they are doing is not working. But if it is working for them, it would be better to ask questions about what colors they have used and not insinuate that the colors that they chose were inappropriate.

Be very careful not to quickly make a statement that sounds judgmental or ask a question that the child simply cannot answer. This might make a child feel like what they are doing is not good enough, is not correct, or is not appropriate. We want that child to enjoy what they are doing. We want them to be able to tell us about what they are doing because that helps reinforce the skills that are being built during that activity.

Avoid conversation stoppers. Think twice before you just try to scurry a child out of a situation or you try to correct something that they are doing. Think of a way to turn it into a good conversation rather than just a directive to that child.

Paraphrase Reflections

The next strategy is called paraphrase reflections. These are very similar to the behavior reflections, except instead of directing our comment to a child based on the behavior that we see, these are restatements that we are directing to a child in response to something that they have said to us. Paraphrase reflections:

- Are restatements

- Allow an adult to restate a child’s original message in different words

- Allow a child to know he/she is being listened to

- Acknowledge the child’s efforts to converse

- Assist listener in being more focused on the child’s words

- Emphasize what the child’s message and meaning

- Place control for the direction of the conversation with the child

- Allow the child to elaborate and expand

- Context can help adult rephrase the child’s message

You can use a paraphrase reflection anytime a child says something to you. It allows a child to hear what they have just said but in your words. It gives you a chance to restate what they said instead of correcting it in a punitive way. Back to the example of the child who said, “Mrs. T I brunj you some flowers.” To restate what they said you could say, "Oh, you brought me some flowers." By restating it so that the child heard it, they knew that I acknowledged that they brought the flowers to me. This lets children know that they are being listened to. They understand better that we heard what they said. There are many times where a child says something to you and you truly do not know what they said. Sometimes we restate what we think that child said, and then they try to help us by saying it again.

A paraphrase reflection can ultimately help you decipher what a child is trying to say to you. Sometimes we say, "Now, what are you trying to say?" If you do that often enough, children eventually give up and think, "Okay, she cannot figure out what I need. I am going to just stop this conversation." We do not want that to happen. We want to use what the child says to let them know, "Hey, I heard you, I am trying to understand what you are saying, and I need you to help me." Again, it acknowledges the child's efforts in the conversation.

Paraphrase reflections assist the learner or the listener and make sure that we truly are focused on what the child has to say. This also helps focus our listening. If we know that we are going to paraphrase and say something back to a child, we are going to listen a little more closely to make sure that we truly are hearing what that child says. Again, it helps us make sure that we understand the child's message and meaning. When we restate something back to a child, it puts the control of the conversation back to the child so that they can say something else. We may not have a question and we may not have an answer related to what they say, but if we direct a restatement back to them, then the ball is in their court, and they are able to serve that conversation back to us.

When we use paraphrase reflections, it might help a child be able to elaborate and expand on something that they are saying. A restatement may give the child more language that may help them elaborate on what they have said the next time they say something to us. I recently listened to a conversation between one of our preschool children and one of our practicum students. The preschool child said, "My birthday's when it snows." Without hesitation, the practicum student said, "Your birthday's in the winter?" She made it a question, but also more of a statement to help that child understand. Then she said, "Okay, well, when it snows, that is typically called the winter. That is when my birthday is. My birthday is when it snows. That means my birthday's in the winter." This child's birthday was in November. Everything was accurate but allowing that child to hear some other words may have helped expand their vocabulary and expand their conversation attempts.

It also helps if we understand the context of the situation. It is important not only to listen with our ears but to be very aware of what is happening in a situation. That can help us in rephrasing a child's message.

You can use paraphrase reflections anytime a child says something to you. You can simply restate or have a couple of restatements to help that child understand that you heard what they said and that you understand what they are trying to get across. It should not be worded as a question, because we are not questioning what the child said. We are trying to let the child know, I understand what you are saying.

One example of paraphrase reflections is when a child points to some vegetables on their plate at a meal and says, "This yucky." You might say, "You do not like the vegetables,” or, “You do not like carrots," or, “This tastes bad to you.” There are so many different ways to try to decipher what this child is saying and many ways to restate "this yucky." It is giving that child some other words to fill in the blanks for, "This is yucky. I do not like it."

Another example is when you have a child that is excitedly carrying a puppy and says, "We got a new Spot." Using the context of seeing a puppy, hearing that something is named Spot and what you have is new you can determine the child has a new puppy named Spot. You can say, “You have a new puppy named Spot.” That is a simple restatement to let a child know that you understand they are trying to tell you that their puppy's name is Spot. Maybe they had an old dog named Spot, and now this is a new dog named Spot.

Use clues to help you better understand what a child is trying to get across to you. I encourage you to use some paraphrase reflections but try not to overuse them. You do not want to repeat everything that a child says to you because that will certainly stop a conversation. It is not a mimicking type of strategy and we do not want to parrot everything back to that child.

Effective Praise

The last strategy is using effective praise. We know that children need a lot of positives in their life that are used in a manner that the child understands that what they have done is a good thing. It should help boost their self-esteem. We want to be really selective and use praise when it is truly deserved. We tend to use the terms good job and way to go a lot. That is not selective. It is very generic. It is not pointing out a specific child and explaining, this is what you are being praised for. For praise to be effective, you want it to be selective and specific. Use it when it is deserved and be very specific. Use explicit information about what is being praised. Children understand that "Good job" is a blanket statement. They do not understand what a good job is or who did a good job. They tend to start tuning that out because it is so generic.

If you think about participation awards, those are not effective praise. My son was playing something similar to Pee Wee Soccer in kindergarten. He was mostly interested in what snack was being served after the game or after the practice. It was not about the athletic portion for him. At the end of the season, all the children got a trophy and a little certificate that outlined something spectacular that they did. After the little ceremony was over, my son looked at his trophy and his certificate and said, “I don’t know why I got this. I didn’t do anything.” He knew that it was not targeting something that he specifically did. That praise did not help him in any way. It did not help build his self-esteem. It did not help him do something better in the future or encourage him to keep doing something. He just knew that it really did not matter to him.

Characteristics of effective praise:

- Acknowledges the child

- Is specific

- Compares event to past performance

- Links actions to enjoyment or satisfaction

- Attributes success to effort and ability

- Is thoughtful

- Natural sounding

- Is not intrusive

One characteristic of effective praise is to acknowledge the child. It is best if you actually use a child's name in their praise. "Parker, you did such a good job helping pick up the blocks in the block area. I really appreciate it." Be specific and outline exactly what they did and why you are praising them. Sometimes children do not understand why you said, “Good job.” They might think, what was so good about that? Be specific and explain why that was a good thing. It is nice if you can use praise to compare a child's performance to something that they did in the past, such as, "You climbed to the top of the high dive. I remember last year when you would not go that high." That is praising something compared to what they have done in the past.

Effective praise can also link what they did to their enjoyment or satisfaction. For example, “You looked so excited when you did this. I know you must have really enjoyed it.” I am giving a little bit of detail to what that child might have been feeling in that situation. Effective praise also attributes their success to their effort and ability. If my son's trophy would have been for best eating the snack after soccer he might have believed that it was really directed to his ability instead of, "You did a great job trying to keep the ball out of our goal." You want to let the children know that their effort and ability are noted and that it is important.

You do want praise to sound thoughtful and natural sounding. I used to work with two-year-olds that were potty training. Very often another coworker would say, "Come tell Mrs. T what you just did." When a child had used the potty I would get this high-pitched very fake voice and say, "Oh my gosh, you did such a great job!" It was not natural sounding. It was probably very annoying to the child. Looking back, I realize how annoying it was. It was not natural sounding. The child is going to think that you are overreacting. They are probably not going to take stock in that praise that you have provided for them. Make sure when you are delivering praise, that it sounds natural.

Also, when you are praising children, try not to embarrass them by drawing attention to something that they did. This is especially important with children that are a little bit older. When you call them out on something that they have done, they may shrink back and be embarrassed. They do not want other people to know that they have done something that may have been deemed as good. To avoid this, I have used post-it notes with children to let them know what they did or talk to them privately, not in the presence of everyone else. These things can help children so that they do not feel self-conscious about being praised for something that they did. The younger the child, the less they worry about this. As they get older, they do start worrying about what other people are thinking. Be cognizant of the fact that not everybody wants their praises shouted from the rooftop. Some children do want to keep things to themselves a little bit.

Figure 7. Girl holding trophy.

Let's look at formulating effective praise. Figure 7 shows my daughter, who was in a competitive dance group. This was the first year that they had done anything in their competitions. At the first competition that we went to, the girls were out on stage and were doing their thing. All of a sudden, somebody forgot what they were doing. Everybody stopped and left the stage. As parents, we were watching and trying to figure out what happened? I do not remember that being part of the dance. They were so overwhelmed that they left the stage. However, they did not give up and they did not quit. We kept encouraging them and they kept practicing. At their next competition, they got a trophy. I do not think that it was a first-place trophy, but they stayed on the stage and they got something for their performance. That was a huge accomplishment. They were so excited and passed the trophy around and everybody had their picture taken with it, by themselves and group pictures.

When formulating praise for Samantha in that situation I had to think about what went into it. For example, "Samantha, you look so excited that you guys got that trophy. Last time you did not stay on the stage and this time you guys stuck it out and look what your hard work did." Being very specific and letting that child know exactly what they did in order to achieve what they are being praised for is huge, in this case from the trophy. Make sure that children understand what they have done and that they can continue that momentum. They can continue working toward their goals and they feel good because you acknowledged specifically what they could do.

Figure 8. Children building a tower.

In figure 8 you can see children that are building with some magnetic tiles on a light table. Be very specific with your praise. For example, "It looks like you two have worked really hard to work together to build such a tall structure." If you know that they had trouble building the structure in the past, you might remind them. "I remember when your structure wouldn't be very tall and it kept falling down. Look how hard you have worked to keep your pieces together. It is nice when we work together."

There are so many things that we can say to help specifically praise what children have done so that hopefully they will continue doing those things in the future. Praise is a great motivator. It certainly can spark conversations, but it is also giving children a positive verbal environment. They are hearing good, positive things about what they are doing, instead of somebody focusing on behavior that might be inappropriate. Focus on the good and let children know specifically what they have done to warrant your attention.

Practice using effective praise and try to eliminate saying, "Way to go,” and, “Good job." Give children specifics about what they have done so that they can continue doing these awesome things and hearing good things about what they have done.

Putting it Together

Take every possible opportunity to visit with children in the natural moments that you are with them, whether it is at snack time, changing a diaper, riding in a car with a child, or pushing a child on a swing. Take advantage of those moments to talk to a child.

Ask questions about what is happening to reflect on what you see them doing. Take time to try some of the strategies and use a behavior reflection. Try a new strategy every day. Make it a point that the next time you are working with a group of children that you are going to point out what two children are doing. Just to give them a statement of what they have done.

Practice sparking conversations with children or practice sparking conversations with people you really do not know. Sometimes practicing with adults will help you practice doing that with children as well. Take a day where you are practicing repeating something or paraphrasing something that a child has said to you. This will help you further understand the child, help that child understand that you are listening to them and that their message has gotten across to you. Take another time to practice using effective praise.

Catch yourself when you are using those generic terms, such as, “Way to go!” or, “Great job guys!” Find ways to be very specific about what a child has done and try not to overuse those generic attempts at praise with children.

I hope that you are able to use these tips and strategies in your work with young children because it will help those children gain so many skills when they see that you are attentive and you are helping them build skills and feel good about themselves in the process.

Questions and Answers

Many people work where there are two people in a classroom, whether they are co-teachers or there is an assistant and a lead teacher. What if one person is trying to use the strategies and the other is not? Do you have any suggestions for teachers that might find themselves in a situation like that?

Yes, that happens a lot, especially since we work with people who are training to work with young children. We do a lot of modeling and drawing attention to the fact of what you are doing in front of the other adult, to explain why you are using the type of praise that you are using or giving them some suggestions on how to spark a conversation. I am working closely with somebody that may not be using the most positive techniques by helping coach them through using those techniques. They may not know how to use them. They may see you using them, but they are not sure how to do it themselves. Coaching somebody, giving them prompts on how to use a behavior reflection, and giving them ideas of good questioning techniques for different points of the day working with children are all helpful.

Any other last suggestions you have?

Just keep those conversations going, because that is what children need. They need to have positive conversations to develop relationships so that they feel valued. If they feel comfortable in that good positive verbal environment, they are going to feel comfortable doing activities. They are going to feel confident in their abilities and they will thrive in every area of their development when they have those good relationships with those caring adults.

References

Meece, D. & Soderman, A.K. (2010). Positive Verbal Environments: Setting the stage for young children’s social development. Young Children, 65 (5): 81-86.

Kostelnik, M.J., Whiren, A.P., Soderman, A.K., Stein, L.C., & Gregory, K. (2018). Guiding children’s social development: Theory to practice. 9th ed. Cengage.

Citation

Tankersley, A. (2020). Positive verbal strategies for connecting with children. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23714. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education