Editor’s note: This text-based course is an edited transcript of the webinar, Loss and Grief in Early Childhood, presented by Tami Micsky, DSW, MSSA, LSW, CT.

Learning Outcomes

After this course, participants will be able to:

- Describe a young child’s understanding of loss and death and expected grief reactions.

- Describe the influence of developmental level, reactivation, and type of loss experience.

- Identify how to support children as guided by the Harvard Bereavement Study, the Dual Process Model, and the reconciliation needs of grieving children.

Introduction

I appreciate the opportunity to talk to you about loss and grief specifically in early childhood. I am a social worker. I am not an early childhood educator. I'm going to try to give you my perspective as someone who has worked with children and families specifically those in child welfare. I worked in a grieving center with children and families who experienced grief and loss, as well as doing some outpatient counseling and now educating social workers on how to work with families who are grieving. I want to give you a sense of what we see when we see children who are grieving a loss and what we can do to help them. What kind of tools and interventions can you put in place, whether it's in the home or in the classroom? I hope that I can at least provide you with that perspective. I have a great deal of respect for what you're doing in working with children of this age as it's such a vulnerable population. The work I did in child welfare several years ago cemented the belief that our children in those young, early years are so vulnerable and need the protection and care of really wonderful people. My daughter is a kindergarten teacher just starting out this year, so I get to hear her stories about the many little five-year-olds in her classroom.

Definitions

What is Loss?

It's important to understand what loss is. Loss occurs when something is left behind by choice or by circumstance. That's a purposely broad definition. For many, when you hear something about loss and grief or you take a grief course, you assume that you're going to spend a lot of time on loss due to death. We will spend quite a bit of time there, but I also want to acknowledge that our children, and we as adults, experience loss on many different levels. If you look at that broad definition, it could just be a change in circumstance. It could even be a choice, especially for us as adults. We could make a choice to leave a job, move to a new state, change homes, or something more significant or negative like a divorce situation. Those choices, or what become circumstances for children who are involved in those adult choices, can be considered a loss. When we have a loss, we often grieve. So even though we often think of loss due to death related to grief, we will also talk about grieving related to these other types of losses as well.

We can think of a variety of different losses. I mentioned divorce, but we can also think of things like military deployment, immigration issues where someone is deported, or even things like drug use or mental health concerns, where a parent or caregiver is physically present, but not emotionally present because of the challenges they're experiencing with their drug use or mental health issues. I'm sure you could name a few more as you listen to me talk about the types of losses. You're probably thinking of other things that you've observed children experiencing, or you've experienced yourself.

When we talk about loss, we typically talk about there being a primary loss and then secondary and symbolic losses around that primary loss. For example, if we think of this related to a loss due to death, we would say that the primary loss is the death of a parent for a young child. That young child would experience that significant life-changing loss as the primary loss, but there are also many secondary and symbolic losses that go along with it or result from that primary loss. A child could experience something like having to move or change schools because the death of a parent meant a loss of income for the family, which meant the family couldn't afford the home that they were living in anymore. Maybe they had to move in with relatives or to a smaller apartment somewhere, which means they changed homes and had that loss, and possibly changed schools which was another loss.

Along with the primary and secondary are symbolic losses that aren't so concrete. It might be a loss of a sense of identity. We often see these more symbolic losses with children who are a little bit older because younger children don't always understand this. We know it's still shifting for them. It's something that at some point in their development, from children into young adulthood and adulthood, they will experience some of those kinds of more symbolic changes.

What is Grief?

We've defined loss so now let's think about how we would define grief. Grief simply is the reaction to a loss. Grief varies widely and is not just emotional reaction. Wolfelt (2020) said, “As human beings, whenever our attachments are threatened, harmed, or severed, we grieve. Grief is everything we think and feel inside of us when this happens. We experience shock and disbelief. We worry, which is a form of fear. We become sad and possibly lonely. We get angry. We feel guilty or regretful. The sum total of all our feelings is our grief.”

While the previous quote is very focused on the emotions and feelings after a loss, we know that those reactions can also involve physical, cognitive, spiritual, and behavioral changes. We'll talk about those things specific to the age groups that we're focused on today. I included this quote because I think it helps us think about attachment and for young children including infants and toddlers, attachment is incredibly important. Think about this in the broad spectrum. Anytime a child feels like their attachment to someone or something is threatened in some way, is harmed, is severed, or has changed significantly, those children could experience some grief reactions. You can see that Wolfelt focuses specifically on some of the feelings, but we'll talk also about some of the other changes that we see because so much for children comes out in behavioral changes as well.

Scope of the Issue

What's the scope of the issue? Why should we worry about this? Why should we care about grief and loss in early childhood? First of all, about a third of America's children live with one parent. This could be single parenting by choice or a divorce situation. There are many different reasons why children are only living with one parent, but whatever the reason, it's still a change. It could signal that there was a loss at some point of one parent.

On any given day, about 400,000 children are in foster care. I'm not going to spend a lot of time talking about foster care, but I think it's important to at least acknowledge that as an issue that we see when we're working with children. Children may be removed from their biological caregivers and placed either in foster care or in a kinship care placement, and maybe even eventually placed in an adoptive home placement. That's a lot of children who are dealing with significant change and loss. Think back to the primary and secondary losses we discussed. The primary loss might be the child is removed from their home and their biological family. Secondary losses could be things like their residence has changed, a change in school, being separated from their siblings, or missing social activities such as sports or church. They may lose those connections. It may be simple things like they don't have their favorite stuffed animal with them or they don't have the sneakers that they love to wear for gym class day. It sounds very simple, but can be very difficult for a child who's used to some kind of structure or normalcy, no matter what that is for them, as it all shifts and changes. For kids in foster care, we may see just the primary loss but remember their loss continues on as secondary and symbolic losses.

We have about a million children of active duty military members worldwide and we know that on occasion, these military members are separated from their children, either when they are deployed, sent for training, or for a variety of different reasons. That is a significant loss for children as well. We know that one in 20 children will suffer the loss of one or both of their parents by the age of 15. This is significant. If you think about your classroom now or your classrooms from previous years, that's probably about right. About one in 20 or about one or two kids in your classroom growing up experienced the death of a parent. One in five will experience the death of someone close to them by the age of 18. When we say close to them, this can branch out to siblings, aunts, uncles, grandparents, or a significant, close friend. As I've worked with college students through the years, I've found that quite a few students (young adults 18-20 years) experienced their first loss of a grandparent. Many may have experienced their first loss of a pet, but the death of someone close to them is typically a grandparent. Oftentimes it can be the death of a friend, such as someone from high school who had an accident or some type of life-threatening illness. Those can be significant times for young adults to experience those types of losses. We know this can happen for our young children as well.

A global statistic is that worldwide at least 5.2 million children have lost a parent, grandparent, or caregiver due to COVID-19. We know that our numbers have shifted and we're still assessing that and seeing what types of losses and changes have occurred because of COVID-19. This pandemic has shifted and changed the world for all of us, but we know children and young adults are all experiencing more significant anxiety and depression. Referrals for mental healthcare are up. All of these things impact our children and can result in losses, which then of course, results in grief reactions.

Understanding of Loss and Death

Let's talk a little bit about the understanding of death and loss at the different ages that we're talking about today.

Understanding of Death: Infants and Toddlers

First of all, what's the understanding of death for infants and toddlers? To understand how they react, we need to understand what they understand. Infants and toddlers have little to no concept of death. They don't understand and don't have the cognitive ability to understand things such as permanency and other things related to death. They can sense change. There was a long period of time where we were told that infants and toddlers don't grieve, that they're okay because they don't have a concept of death and don't understand what's going on. I think we do a better job now of acknowledging that children at a very young age can sense change, especially if the main caretaker is gone or that person is grieving. When I say gone, it doesn't have to be death. If that person is deployed because of a military deployment, their infant or toddler is going to be able to sense and have the cognitive ability to understand that that person is no longer physically present with them. They are also going to react to the emotional distress of that caretaker.

Understanding of Death: Early Childhood

In early childhood, children start to think that death or loss is about separation, but they don't really understand permanency yet. Some kids start to, but in those younger, preschool years, they really don't understand that too much. They do love to know about the biological aspects of death. I'm sure you can relate to that with children's questions about how the body functions. That translates into understanding or wanting to understand how death works. Children at this age often think that death is sleep or because of that magical thinking at this age range, they think that maybe their thoughts, behavior, or feelings could have caused a death or some significant change. They definitely sense emotional distress in the people around them.

Mature Concept of Death

At what age do we get past this and start to understand and have a mature concept of death? The research tells us anywhere from four to 12 years, but typically by about age seven, most children have what we call a mature concept of death. Figure 1 shows some of the factors that go into that.

| Universality | Irreversibility | Non-functionality | Causality | Personal Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|

The understanding that all living things must die. | The understanding that once the physical body dies, it cannot be made alive again. | The understanding that once a living thing dies all of the typical life-defining capabilities of the living physical body cease. | An abstract and realistic understanding of the external and internal events that might possibly cause a death. | The child’s understanding of vulnerability to death. |

Figure 1. Factors contributing to a mature concept of death.

Children need to have the cognitive ability to understand these different factors including that death is universal, it's irreversible, and the body is nonfunctional once someone or something dies. They begin to understand the causality and that there may be events externally, such as accidents or things that happen to people, or internally, such as illnesses that can cause death. Because children understand all these things, they begin to understand a vulnerability to death and understand that, "Oh, okay, if my grandma died, then could my dad die? Oh, wait a minute, could I die, could this happen to me?" All of these factors come together and help children understand the permanency and the universality of death. Because of the personal mortality or mortality of other people around them and understanding that, sometimes we see anxiety increase a little bit or some separation issues.

Talking to Children about Death (and other losses)

Here are some tips so that when you are talking to children about loss or death you use language that's going to help them and not hurt them. You may be working with parents who say, "I don't know how to talk to my child about this. Do you have any ideas, can you help me?" There are a lot of resources out there related to this topic and you can find things online that are very reliable and give you really good information about how to talk to kids about death. This is a big challenge for most parents and for most of us, to talk to kids about these difficult things.

The first tip is to use clear words. Use the words, died and death, if that's what's occurred. Avoid saying things like passed away, lost, or sleeping. As adults we say, "So and so passed away," because it's gentler, it feels better, and we understand that at a different level. We know what that means. Little kids don't always understand that, and they really don't understand when we say grandma's sleeping, or we lost grandma. What they'll say to you is, "Let's go find grandma, then. If she's lost, let's go find her" or, "Let's wake her up" or it could lead to, "I'm afraid to go to sleep because you said grandma's sleeping and grandma can't wake up now." We have to be careful and delineate how we talk about death and dying, specifically with children. Giving clear, age-appropriate information is important.

Expect repeated questions. We know that's what children at this age often do anyway, so they're going to do the same thing about a significant change in their lives. Explain plans for mourning and offer participation for the children. If they want to participate in a funeral or in some kind of separation ritual, that's something that we can plan for them. We know that mourning rituals and participation are extremely important to healing for kids.

Here are a couple of examples of how we can talk to kids or share information with parents so that they feel comfortable talking to their kids about things like divorce or someone who's died. These can be very challenging. It sounds so simple putting it here in words, but it can be very hard for parents or for caregivers to have these types of conversations.

“When a person dies, their body stops working, and they can’t eat or laugh or poop or cry or walk or talk anymore. That means they are dead. When someone is dead, we need to do something with their body, which doesn’t have any feeling in it anymore. Mommy’s body got taken to a place called a funeral home, where they’re taking care of her body for us.”

“Daddy and I are not going to live in the same house anymore. We are getting something called a divorce. We still love you very much and you didn’t do anything to make this happen.”

Grief Reactions in Childhood

Let's talk about grief reactions. There are a couple of things I want to point out before we get into more specifics related to different age groups. Reactions to any type of change, especially death, depend on the child's personality, age, stage of development, spirituality within the family system, and relationship. When I say relationship, it could be the relationship with the person who's no longer present or the relationship with the people around them. This also includes the quality of those relationships and how communication goes within the family. Other factors include how much we talk about things or don't talk about things and how much we include the kids and how much we don't. As you know, children have so much development happening and so much change in the early childhood years that every child is so different. You have to look specifically at the needs of that child and how they're reacting and what interventions or tools are going to fit best for them.

The other thing that influences reactions is the nature of the death or the nature of the change in general. Is it sudden? Is it something that happened in a traumatic fashion or something the child witnessed or was in the middle of a difficult situation? Was this something more anticipated that the child may have had some time to adjust to? There are positives and negatives for both of those, but I just want to point out that it does influence the way a child will grieve. Here are some ideas and things to look for regarding what it typically looks like, but remember there's no prescription to this. If you've experienced a loss and have experienced grief and continue to grieve, you know that this is a lifelong process that depends on so many different factors.

As we look at each age group remember these things are typical but can be very different depending on the child and their situation, any significant needs that they have, and any disabilities the child has. All of that will also influence their reactions.

Infants and Toddlers

| Understanding of Death and Loss | Grief Reactions |

|---|---|

No mature concept of death. | Sense of security and well-being is challenged. |

| Does not have language for expression. | Fear of separation from remaining caretaker. |

| Does not understand time. | Child may display excessive crying, rocking, whining, biting, and/or other anxiety-related behaviors. |

| Can sense change, especially if main caretaker is gone or grieving (emotional distress). | Regression (bottle, pacifier, toilet training). |

| Child may not be able to process death as anything other than separation. | Physical symptoms. |

Figure 2. Grief reactions of infants and toddlers.

While infants and toddlers don't have that mature concept of death, they can sense change. They're not able to really understand death as permanent and just see this as a separation. Separation is still quite challenging for children because of the importance of attachment at this age. There is a risk that adults will underestimate, or what we call disenfranchise, the grief of children because we don't think children can grieve or are grieving at this age. Adults often think since they don't understand they can talk in the kitchen if they're in the living room and they're not going to hear what we're talking about anyway. But we know that children pick up on things and if we ignore or minimize their reaction, then that could actually make the reaction stronger. Those kids could either withdraw more or act out more. There is a high risk for this especially for non-death losses if parents or caregiver don't understand that children at this age group do grieve and do need support.

Typically at this age, we see a sense of security and wellbeing is challenged. So often there's a fear of separation from the remaining caretaker and we see some of that stranger or separation anxiety at certain ages in this area. If that child has a significant loss or change, then that might be increased or you might see a lot of crying and clinginess to their primary caregiver when that child's dropped off. Depending on the situation, we do see kids who go the other way who will go to anybody. When I was working in a grieving center and working in the preschool room, the biggest challenge was separating kids from their caregiver who was bringing them because they had lost somebody close to them, and they just weren't going to let that person go.

We also see excessive crying, whining, biting, and other anxiety-related behaviors and regression. Regression is very common during changes like this throughout early childhood where a child doesn't use the bottle anymore, has given up their pacifier, or started toilet training and all of that goes backwards. Maybe the bottles are back out again, they want their pacifier now, or toilet training doesn't go so well anymore. Sometimes we'll see physical symptoms. This is a time where caregivers may misinterpret that a child has a stomachache or a headache or something and they may not be able to express that. If they're old enough to be able to verbally express that we don't often connect it to grief or the changes that child has experienced, but we do know. We know as adults, when we are stressed or grieving or anxious or depressed, all those things go together. We have physical symptoms, so our children would have the same as well.

Preschool

| Understanding of Death and Loss | Grief Reactions |

|---|---|

May think death or loss is caused by thoughts, behavior, or feelings (magical thinking) | Regression |

May not understand that death is permanent | Sadness, anxiety, irritability |

May want to know about the biological aspects of death and can understand breathing and heartbeat stops. | Fear of separation/clinginess |

May think death is sleep | Repeated questions, curiosity |

Senses emotional distress. | Physical reactions/symptoms |

Difficulty communicating distress in words; communicate in behavior. May show feelings, thoughts, questions through play. | |

Take cues from others’ behavior – if others cry, they cry | |

May intermittently express sadness, listen to explanations, then return to play |

Figure 3. Grief reactions of preschoolers.

Let's look at the preschool age group. As I said, these are a little fluid, depending on the child's cognitive abilities and so many different things. Thinking back to the magical thinking children may have, they may think they have caused the death or loss. I've seen this in kids, five and six years old when the magical thinking is very strong, but I've also seen this in children as old as 10 or 11 years old. I had a little girl say to me, "I really think that if I would've got better grades and not been mouthy to my mom, that she wouldn't have died." It threw me for a minute the first time that this child said that because I thought, oh, you're not in that age group. Like we learned that by that age, you should understand that your behavior doesn't control those types of things. But I think there's a sense of deservedness or a little bit of a sense of karma, or if I just would've been good, then these bad things wouldn't have happened to my family. This can continue more into middle childhood as well. But we also know that these children can sense emotional distress and have a little bit better understanding than the toddler group.

We see some of the same types of things with regression, sadness, anxiety, some irritability, and still that fear of separation with a level of clinginess to the remaining caregiver. There are still repeated questions and some curiosity, wanting to know more. This can be challenging for adults because if they're grieving, irritable, and tired, and they're having all of those reactions themselves and the child is being curious and clingy and irritable all at the same time, it can be a very difficult kind of interaction going on between the caregiver and the child or children, who are grieving as well.

Children at this age may have difficulty communicating their distress in words. They're going to be more likely to communicate through their behavior or act things out in their play. They take their cues from others' behaviors. So if their caregivers or siblings are crying and it's okay, no one's telling them to stop crying, then they may cry as well. We often see that modeling within families of how they're dealing with the loss as well. We know also that children of this age can only deal with emotional pain, concern, or worry for so long. Often at this age, they will ask questions or cry for a little bit or feel upset and then they go and play or go back to whatever they were doing or watching their show. Then maybe an hour later, they come back with more questions or they want to talk about it again. What we found is that children at this age need that intermittent kind of ability to grieve or to talk about what's going on or to share what they're feeling in whatever way that they can.

Young Children

| Understanding of Death and Loss | Grief Reactions |

|---|---|

| Are able to understand the biology of death and comprehend the finality | Feelings of insecurity may be expressed in a reluctance to separate from caregivers |

| May develop fears associated with their own death or the death of a surviving parent | "Hyperactive," aggressive, and disruptive |

| Withdrawn and sad | |

| Nightmares or difficulty sleeping | |

| Regressive behaviors |

Figure 4. Grief reactions of young children.

Young children, so just a little bit older, are starting to understand death and loss in a different way. They have the cognitive ability to understand some of those factors of the mature concept of death. We said often it's by about age seven that a child would still be considered a young child and able to understand some of these things. They may develop more fears associated with the death of a surviving parent, or if someone else going to leave if it's not a permanent loss, like a death. We often see more anxiety in this age group, as well as feelings of insecurity and still some separation issues. They may not be so physically clingy, but there are still some separation issues.

I had a little girl who was six or seven when I was working with her and her mom had died. She was living with her dad and was an only child. She had a very difficult time separating from her dad to go into school at each day. She was so worried about him and something happening to him because her mom's death was very sudden. We had to do a couple of things to make sure that she could separate. They brought her at a different time, which helped so she was a little bit earlier than all of the other kids and the chaos of all the children coming in for the school day. Her dad was able to get a picture of mom and put it in a necklace so she could have that all day. She was also able to call dad about lunchtime. She made a phone call to dad to check in on him, and eventually like that faded and she didn't need that anymore. Those were some of the ways that we helped her feel more secure and to be able to separate so she could keep functioning and doing the things that she needed to do during her school day.

We also see kids who have aggressive behavior and sometimes term them as hyperactive. We often think of these kids as disruptive and may not recognize that these could be grief reactions as well. There's anxiety and all this stuff built up for this child who's fearful, worried, and doesn't know what's going to happen next. The child feels like the world is outside of their control. Sometimes it comes out in an aggressive or disruptive way. It could also come out in a withdrawn and sad way as well. So we have both ends of the spectrum. Then there are all the children who fall somewhere in between.

We do see a lot of issues with nightmares or difficulty sleeping and children still having regressive behaviors. The sleep issue we often see is with kids who've been told that the person who died is sleeping or the child has nightmares when the child hasn't been given much information about the change, or if there's been a divorce or a not permanent separation that the child may not have all the information. So in their dreams or nightmares, or as they're trying to get to sleep they create a kind of understanding or their own picture of what has occurred.

Children aged five to seven are particularly vulnerable to complications of grief, so they can understand some of those permanent ramifications. They understand their own mortality, the mortality of other people around them, and how change can happen very quickly. At the same time, they lack independent coping skills. Maybe we haven't done a great job with our young preschool children and young school children in helping them to independently cope. It takes a while to learn coping skills. As adults, we are all still learning coping skills and how to use them appropriately. This is where we see some pretty significant risk of children experiencing grief as they try to understand the death of someone very close to them and the permanency of it, but not being able to cope with it, especially if they don't have the support in their family or in their caregiving situation.

"Reactivation" of Grief

We also know that children will experience what some research has called reactivation of grief. Grief reactions can be reactivated as children age and go through various developmental stages. As they develop their cognitive skills, language skills, and social skills, they understand and process these losses differently. You can see how a child who had a significant loss, such as a loss due to death at two or three years old won't have an understanding or a mature concept of death. They may have grieved because of the reactions around them or had some separation issues, but when they become seven, eight, or nine years old and begin to understand the permanency of the death and that this person is not coming back and they don't really remember them that well, there may be some grieving. We see this even more significantly in the teen years. In adolescence, they really understand death as permanent. Then you often hear the why me questions and adolescents asking, why am I different? That's the last thing we want to be in the preteen and teen years is different from everyone else.

It's important for parents to know that grief is going to continue throughout a child's life. We don't want to hear that. We all want to hear that you go through stages of grief and then you're done. But the reality is that theory was misinterpreted in many ways and is something that we've moved on from. In modern grief theory, we understand that grief is a lifelong process. It is absolutely a lifelong process for children who've experienced the death of a loved one at a young age, and then have to reprocess it at each point where they understand it differently or have different experiences. We often talk about anniversary reactions as well, where both children and adults may be triggered with their grief because of an event such as a graduation, wedding, holidays, birthdays, or anniversaries, which can bring up reactions of grief again.

Death of a Parent

I want to talk briefly about the death of a parent and the death of a sibling. These are significant deaths and it's important to understand if you're working with children who've experienced this type of loss. We typically see pretty significant reactions, but again, they are so dependent on so many different things. These children experience a loss of security, sometimes nurturing, and maybe some affection because even if it's a two-parent home and a parent dies, that parent who's left to care for that child or children may not have the strength, emotional stability, support, or the resources to be able to provide nurturing or affection when they're grieving themselves. They may be able to, so I'm not saying it's not possible. However, there is a high risk of it not happening because that person is dealing with their own grief as well as trying to take care of children and their grief. There can often be a loss of emotional and psychological support. Sometimes we see additional responsibilities for children who've lost a parent, and sometimes it's out of necessity. Sometimes children step in out of their own accord, thinking that they're pitching in or helping their remaining parent.

Death of a Sibling

The death of a sibling is also significant and can change the functionality of a family system. If children are able to understand it, depending on their cognitive ability and understanding of death, they may understand that they are also vulnerable, especially if their sibling was close to their age. They have a sense of not only losing their sibling but also losing their parents because they're just not the same as what they were prior to that sibling's death. They may have a loss of a protector or caregiver, as well as a playmate, depending on the age difference. There's often a mixture of emotions, including some level of guilt or confusion. Kids often say, why wasn't it me? They may be confused about why this happened to their family. If they don't have all the information about what happened specifically, then they're going to have a lot of questions and confusion about that as well. Again, it may set in motion dysfunctional family patterns. Sometimes parents will minimize contact with the surviving child and not be as nurturing and connecting to that child because they're fearful of the pain of losing another child. On the other side, parents may be overprotective of the surviving child and that child may feel like they don't get to do things. As they get older, those kinds of feelings can be more challenging as well.

Death of a Pet

I also want to mention the death of a pet, because this is often a young child's first introduction to death. It may be a goldfish, hamster, or a class pet. These provide opportunities for children to learn about death and caregivers, whether parents, educators, or extended family, can model feelings about a loss and about the death of this pet. Remember to use simple and direct language. We don't want to say put to sleep, although that feels much easier to say. In our own lives, we use those things, but again, children aren't going to understand that. We need to explain what that means. What does euthanasia mean for a pet if that is what happened?

If possible, involve children in the ritual and explain what will happen to the pet's body. For example, you may have participated in a ritual where you had a goldfish and buried or flushed the goldfish after it died. Those are often seen in skits and sitcoms on TV, but it's the reality that can teach children how to handle this and how we react to a significant loss. How do we incorporate rituals so we remember this important part of our lives? It may just be a goldfish or a hamster, or it could be that cat or dog that we've had for many years. We want children to see what we do as a model. We also recommend that you don't replace pets immediately. That's often the first thing we think of because it's so easy to do. We can just go out and get another hamster, but children need to understand and feel that loss a little bit and see how parents model the reaction to that. Eventually when they're ready and the family's ready, if it's something that they want to do, then replace that pet.

Helping Children Cope with Loss

We've spent a lot of time talking about all the reactions and the tough things that we see our children going through, but how can we help them? How can we help children cope?

Harvard Bereavement Study

Harvard conducted a bereavement study of 125 school-age children from 70 families where one parent died. While you are likely working with children younger than school-age, this study gives us a good sense of what can help children of all ages and adults as well. There was a nice, strong focus on family involvement and what works for families within this study.

They found some protective factors we can use as we work with families or incorporate into classrooms and what we're doing with the children we're working with. Since this study focused on loss due to the death of a parent, there was communication about what happened as well as continued discussion about the parent who died. They didn't hide all the pictures and pretend like the person wasn't there. There was continued communication and sharing.

There were fewer secondary disruptions, which is not something we can always control. As I talked about before, we can't always control the loss of income, change of home, change of school, or things like that, but it is something that was found to be a protective factor. If there is something that a family can control or something within an education setting we can control, it helps to keep that child in the same kind of setting and have that structure. We also saw families with active coping, that were actively looking to cope with this and not ignore the changes that they've experienced.

The functioning level of the surviving parent was the most powerful predictor of the child's adjustment. What that tells me is we shouldn't just think about the children and help them and give them coping skills and opportunities to express their feelings. We should also think about how we can support the parents who are continuing to parent these children and trying to cope with their own change and loss as well. The study also found funeral preparation and participation were important.

Continuing bonds, which is actually a whole area in the modern theory of grief and loss, focuses on continuing to maintain a connection with a person who is no longer present. We often talk about this related to loss due to death, but we can talk about it with divorce, deployment, or any other type of separation where we want to try to maintain that connection. We want to talk about that person, think about that person, and memorialize them if it is a person who's no longer physically present. Overall support, nurturing, and continuity in that child's environment are important.

The study found that bereaved children need to know that they will be cared for and that they did not cause the death. This may take some convincing because what we find is that if kids haven't been told the details, even minor ones, they can create stories in their minds and fill in the blanks themselves. Often they may wonder if they did something wrong that caused this. They need clear information about the death. They need to feel important and involved in the process. They need to continue routine activities. They need someone to listen and they need ways to remember the person who died.

Remember, this study was focused on a loss due to death, but think about all the things the study found. A child who's had a significant change, such as a divorce situation, also needs these things. We have so many different changes in our lives right now and every child needs these things. They need to know that they'll be cared for and that they didn't cause this change. Children also question why their parents got divorced and wonder if it's because they did something wrong. They want clear information about what's going on. They need their routine, they need structure, and they need people to listen. All of the things that this study found can be applied to other losses as well.

Coping with Loss

Coping with loss and change is not an orderly process. As I mentioned earlier, grief does not happen in linear stages. If you've experienced loss you likely know this. Many adults I talk to say, oh, it's not the way they say it is. It's not the way the old school theories like to tell us it was. It would be nice if we could just step through some stages and be done with grief, but we all know that's not possible, especially for our children who are going to be grieving over their whole lives. Children, like adults, experience grief in different ways. Therefore, their paths to healing are going to be a little different as well. They can experience reactor activation or re-grief as they move through their developmental stages. Children, like adults, can experience those triggers in anniversary reactions as well. I mentioned some of the anniversary reactions with holidays and special events and things like that, but we also can be triggered by a variety of different things and children are no different. It could be a smell, a song, a location, a specific food, or many different things that remind the child of the person who's no longer present. Because of that, they can have what we call re-grief or reactivation of the grief.

How to Help

Here are some basic tips and simple things that any of us can do to help children who are grieving. We can maintain normal routines and familiar surroundings. When we have children who experience significant loss or change, and we can say this simply about the pandemic, we don't want to change our surroundings or change our routines when we're all experiencing significant losses or significant changes already. Why change anything else? Try to keep things as routine as we can. Provide a consistent caregiver. If you're working with children in an educational setting or a caregiving setting, it's important to try to keep those caregivers consistent. Make sure those children who've experienced a loss see the same people every day. Children need nurturing, attention, hugging, and love. Remember, not all children are as welcoming with those types of things, but if it's a child who needs that connection and can have that with you or with their parent, that would be incredibly important as well, because it's a comfort. It's a comfort for them and it's an attachment that we need to continue.

Children should be able to hear about the changes in terms that they understand and how they will affect them. Think about this with a divorce situation. They may be wondering how it affects them if mommy and daddy aren't going to be living together anymore. Where am I going to live? How long will I be here or there? What school am I going to go to? Am I going to go back to my daycare? Am I going to still be able to play soccer? Those are the things that they're going to want to know about, so we need to be very clear about those items. As I mentioned previously, be sure to provide consistent, gentle, physical and verbal reassurance and comfort.

Express confidence in the child and the world. For children, it often feels like their world turns upside down when they've had a significant change. Remind them that things are going to be stable, we're going to be okay, and have supports, resources, or connections pointing those things out to children. Building that confidence in what's going on around them can do wonders as well. Provide them with terms or vocabulary for their feelings. Many of you may already be doing this with the young children that you're working with. That's incredibly valuable when we're talking about grief and loss because many children don't have the words to express their feelings. If we can teach them that and if we can help them to understand and put together some kind of way to express their feelings and then put words to it, then that's going to come together so they can verbally express what they're feeling at times. Also, as discussed previously, reinforce that they didn't do anything wrong.

Dual Process Model

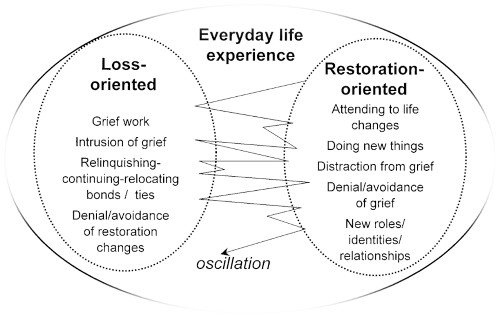

Another model that I use a lot is the Dual Process Model. I like to use this because it's a more modern theory of grief and I think it fits a lot of different contexts. The Dual Process Model says that when we're grieving, and this can apply to children or adults, we have a loss orientation and a restoration orientation as seen in figure 5.

Figure 5. Dual Process Model.

We oscillate between those two daily, weekly, yearly, or whatever it takes. But for most people who are grieving, they're going to have times where they're focused on the grief, where the feelings are there and there's almost an intrusion of those feelings or remembering or thinking about what's going on. It's the tough times when all those feelings or the inability to concentrate or the physical reactions can come forward as well. We're not thinking about what's changed or trying to move forward, we're really focused on the hard stuff when we're on the loss-oriented side.

The restoration-oriented side is when we think, okay, things have changed, this is what I've got to do about it. I'm going to do new things and try to avoid thinking about the feelings or the tough stuff right now. I may even just distract from the grief by going to a movie with my friends. I may start to connect with new relationships, maybe take on new roles out of necessity or out of just trying to do something different. This theory says we can do all of that in a day, we can go back and forth. Children may do this in an even shorter span, where they talk about it for just a few minutes and they're off distracting themselves by playing with toys, playing soccer, or doing something fun that distracts them from the difficult stuff that's going on. This really fits for our children who are young and can only cope with those feelings or hold those feelings in intermittent ways, over short little spurts of time.

We know that adults can do the same thing, but often for adults, it can go longer. Because as adults or even teens, young adults can hold that pain a little longer. They could sit in a support group and talk about their grief for an hour, where of course, preschool children can't do that. It does shift a little with the timing, but you can see how this could be possible even for young children and how we could build in opportunities for children to have some of this loss orientation and restoration orientation. It's normal and it supports healthy grieving. So how can we build this into our work with kids? These reconciliation needs go hand in hand with the Dual Process Model. Here are Wolfelt's reconciliation needs of grieving children.

- Acknowledge the reality of the death.

- Move toward the pain of the loss while being nurtured physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

- Remember the person who died. (Maintaining connection)

- Develop a new self-identity based on a life without the person.

- Relate the experience to a context of meaning.

- Receive ongoing support from others.

Notice the first three are more focused on the grief side or the loss orientation. The last three are more focused on restoration. I'll go back for a second. Figure 5 shows the Dual Process Model focusing on the feelings, the tough stuff, and talking about the person who died or who's no longer present in the loss orientation. Thinking about a new identity and having support from adults or other people is more of the restoration side. You can see how a lot of this grief work and grief theories really overlap and how we can use them to help and support children. Let's talk about these reconciliation needs.

1. Acknowledge the reality of the death (or other loss). First of all, we need to acknowledge the reality of the death. This is simply allowing a child to talk about it, allowing them to say the words, having discussions as we talked about, and avoiding messages to move on or to be strong. This is influenced by the developmental understanding, or the mature concept of death as well, but understanding loss and all of the things that go along with that is going to depend on where that child falls in the development of that understanding as well.

2. Move toward the pain of the loss while being nurtured physically, emotionally, and spiritually. We want children to move toward the pain of the loss while being nurtured. We're not sending children out there to do this on their own. We want to be there to support children as they process the pain, to talk about or express feelings if they don't have the vocabulary to do that, and give them permission to express their grief. Avoid the tendency to protect children from difficult feelings. I don't know if you heard it when you were young, but I can remember hearing, don't cry, it's okay. That's what we want to say to our kids because we want to comfort them. It's our norm in this society to avoid discomfort. Of course, want to protect our children from crying or feeling sad or frustrated, but in this instance, they need to have that loss orientation. They need to spend some time focusing on processing this grief and loss. They need permission to mourn and mourning is an expression of grief, so they need to be able to express it in some way. Be prepared for children to express grief intermittently because they can only hold the pain for so long.

Create opportunities for children to process their pain through creative outlets. This is something you can do in homes with families or in your classrooms. Give them opportunities through their play and have items such as puppets, dollhouses, dress-up, painting, and all of those things that children love. This is also a great way for them to express their feelings and what they're thinking. Kids who are a little bit older in their young childhood years can definitely do some activities around feelings. There are so many printables and activities that you can find for them to do. Art, dance, and music are also wonderful ways for children to express themselves.

3. Remember the person who died or is no longer present (maintaining connection). Children need to remember or maintain connection, depending on the circumstance of the change or loss with the person who's no longer present. If it's been a loss due to death, we encourage parents to have their children participate in the funeral because we want there to be a shift from a relationship of presence to a relationship of memory. We want to continue that bond through memory sharing, keepsakes, sharing photos, and things like that, but we also need it to shift from presence to memory. That helps children to make that connection or make that shift. We also want to think about negative or complicated memories and experiences for children.

What we may find is children may not have memories, because they were young enough when that person was no longer present that they don't really remember that person. Encourage parents to share photos with the child. We also have children who may have complicated or negative memories about the person who's no longer with them if it was a difficult, abusive situation, domestic violence, substance abuse, or mental illness. Those types of things can bring up some difficult memories or issues for kids as they're trying to process all of this. We want to be prepared for that and allow for it. Just because the memories are difficult, doesn't mean kids don't want to share those and have the opportunity to do that.

4. Develop a new self-identity based on a life without the person. This one is a little tough with early childhood, but I wanted to at least include it because it is one of the needs which is to develop a new self-identity. This is a developmental process as children shift and change related to their identity over their entire developmental process. We see this more coming into play in preteen and teen years because identity is so much a part of what they're developing at that point in their lives.

Sometimes when there is a death or loss, people talk to children, even very young kids, about how now you're the man of the house, or take care of your little sister. Those well-meaning relatives and neighbors often say these things at funerals or when someone is going through a divorce. That can put a lot of pressure on a young child and sometimes they take that very seriously and very concretely. Sometimes they believe that they are the man of the house now, so they need to do all of these things and fill that role that's now empty. That can change that child's identity and sense of self. Be careful about allowing that to happen. Make sure to allow time for play and fun, that restoration side. Kids need to be able to do that. Allowing for control and choices when possible. Children who've experienced a significant change or loss feel like their whole world is out of control so they're going to try to control everything they can. When it's possible, we want to give them some opportunities to control some things.

5. Relate the experience to a context of meaning. Another need is for children to relate the experience to a context of meaning. Again, this is a little bit higher level developmentally, but we can also associate this with spiritual and religious beliefs, which have to do with the family's beliefs and what they want to talk to children about. Many people believe in heaven and talk to children about how if a loved one has died, they have gone to heaven and children can make some meaning associated with that. We do have to be careful because we've had some families who will say things like, so and so is watching over you, or they're an angel and they'll be watching you. That can scare kids a little bit, especially when they cognitively don't understand all of that. We have to be careful how we talk about those things and help parents to talk about that as well.

We expect the how and the why questions, but it's okay for parents, caregivers, and providers to acknowledge that we don't have the answers. We're never going to have all the answers. This is a perfectly acceptable time to say that as well. This does give children an opportunity also to begin to develop and practice empathy as they think about how all of this affects everyone around them as well, and not just themselves. It's that meaning and understanding of why and how this happened that can help children to grow and be positive in many ways if discussed in the right ways.

6. Receive ongoing support from others. Finally, let's talk about receiving ongoing support from adults. There's a long-term nature of grief that I have talked about with the reactivation and the re-grief. Children are going to need long-term support over time. We also need to understand those triggers and holiday reactions and ensure that children have an adult stabilizer. They need to know that there's somebody who will be there throughout the entire process to provide support, to communicate, and be a model of healthy coping and healthy grieving.

Play

Play is so important. I know I'm preaching to the choir here because we know that children learn, process, and develop related to their play. Play helps with so many things, and this is no different. Processing their grief and loss experiences often happens through play. Provide children with items such as a punching bag they can hit, a soccer ball they can kick, or an old phone book, magazine, or another disposable item they can tear up to physically express their grief. Let them use puppets as a way to express their feelings. Then it's not really them, it's through something else. Children can use dolls and dollhouses to act out things that they've seen or what they're thinking may have happened. As I mentioned before, using creativity and creative outlets is important as well.

Books and Bibliotherapy

Another thing that I loved to use when I was doing more outpatient therapy with children and groups was books. Here are some lists you can look through and find some books that may appeal to you and the situation your children are coping with. Many are readily available from book vendors.

- Book List – Loss due to death: https://whatsyourgrief.com/childrens-books-about-death/

- Book List – Deployment: https://themilitarywifeandmom.com/books-for-military-kids-during-deployment/

- Book List – Divorce: https://www.parents.com/parenting/divorce/children/books-that-help-explain-divorce-to-kids/

- Book List – Immigration & Deportation: https://www.readbrightly.com/books-about-immigration-for-kids/

What'syourgrief.com has other great resources as well. You can find some great children's books that you could use in your classroom or with parents and provide to parents to use with their kids. I loved using them in groups with children and then doing an activity that correlated with the book. Children love those kinds of connections and creating something.

Resources

Sesame Street has excellent resources for helping kids grieve that connect very easily with children and parents find approachable as well. They have articles, videos, and printables that can be used. The Dougy Center is a grieving center that has wonderful resources for all different types of grief issues. I specifically gave you the link to preschool age and daycare age tip sheets that they have, but if you look around on their website, there's even more information that could be valuable for you in many different ways or things that you could provide to parents.

- Sesame Street – Helping Kids Grieve - Articles, Videos, Printables

- Dougy Center

The Wolfelt book on helping the bereaved child is where the reconciliation needs came from. If you're really interested in this type of work, it's a great resource. It's a little bit older, but it's wonderful. It's really easy to read and easy to understand. I use it in my grief and loss class with my social work students to help them know how to work with kids who are grieving. I highly recommend that one among others, but that was one of the great resources.

References

DeSpelder, L. A., & Strickland, A.L. (2015). The last dance: Encountering death & dying. McGraw Hill Education.

Jewett-Jarett, C. (1994). Helping children cope with separation and loss. Harvard Common Press.

McCoyd, J. L. M. & Walter, C. A. (2016). Grief and loss across the lifespan: A biopsychosocial perspective (2nd ed.). Springer Publishing.

Walsh, K. (2012). Grief and loss (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Wolfelt, A. D. (2013). Healing the bereaved child: Grief gardening, growing through grief and other touchstones for caregivers. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

Worden, W. (2018). Grief counseling and grief therapy: A handbook for the mental health professional. (5th ed.). Springer Publishing.

Citation

Micsky, T. (2022). Loss and Grief in Early Childhood. Continued.com - Early Childhood Education, Article 23792. Available at www.continued.com/early-childhood-education